Equal Gold Bands: Reflecting on Lesbian Marriage Plots

By Hannah Roche

“This theoretically sophisticated reading of three lesbian writers—Stein, Hall, and Barnes—is at once playful and serious. Roche’s insistence on the queerness of desire, romance, and love between women takes feminist modernist studies in an exciting new direction. ”

~Laura Doan, author of Disturbing Practices: History, Sexuality, and Women’s Experience of Modern War

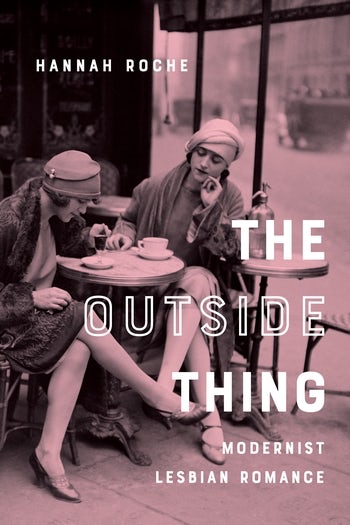

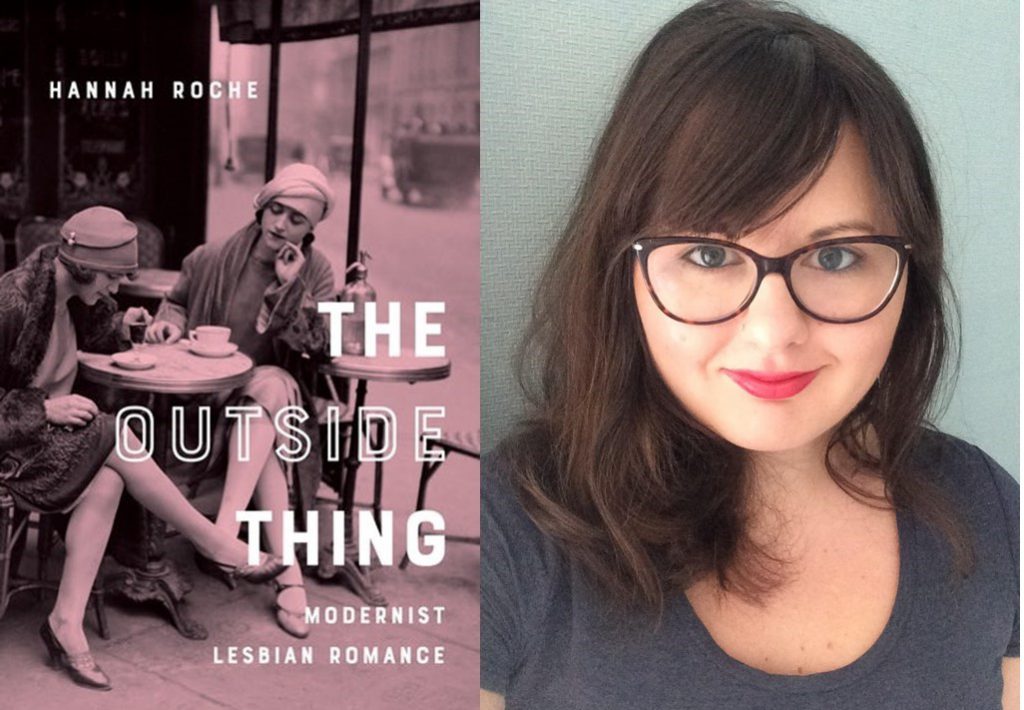

Today we are exploring romance through lesbian literature with this guest blog post by Hannah Roche, author of The Outside Thing: Modernist Lesbian Romance. Enter our Valentine’s Day giveaway for a chance to win a copy of this work.

• • • • • •

Some fifty pages before the notoriously bleak ending of The Well of Loneliness (1928), Radclyffe Hall’s doomed lesbian lovers attend a wedding. On a fine June day in Paris, Stephen and Mary’s young housemaid Adèle and her beloved Jean are “made one flesh in the eyes of their church, in the eyes of their God, and as one might confront the world without flinching.” Stephen provides the dress, the wedding breakfast, and the car; Mary gives the bride her veil, shoes, and stockings; and David the dog is assisted in the purchase of a gift of a large gilt clock. But while Adèle and Jean look to a future of “security, peace, and love with honour,” Stephen – whose masculine appearance prompts mirth and mockery from guests at the wedding – knows that she and Mary can never marry. As if to hammer home the point that happy endings are the preserve of heterosexuals, Hall’s next chapter sees the death of a lesbian couple: Barbara falls victim to double pneumonia, and her partner Jamie takes her own life.

But all may not have been as hopeless as it seemed. While Hall’s sapphic salon hostess Valérie Seymour – a character based on writer Natalie Clifford Barney – was pointing out the absurdity of Stephen’s decision to engineer Mary’s marriage to Martin (“of all the curious situations that I’ve ever been in, this one beats the lot!”), other writers were playfully approaching the idea of lesbian marriage. Djuna Barnes’s Ladies Almanack, privately printed in Paris in 1928, voices caricatures of Radclyffe Hall and her long-term partner Una, Lady Troubridge:

Just because Woman falls, in this Age, to Woman, does that mean that we are not to recognize Morals? What has England done to legalize these Passions? Nothing! Should she not be brought to Task, that never once through her gloomy Weather have two dear Doves been seen approaching in their bridal Laces, to pace, in stately Splendor up the Altar Aisle, there to be united in Similarity, under mutual Vows of Loving, Honouring, and Obeying, while the One and the Other fumble in that nice Temerity, for the equal gold Bands that shall make of one a Wife, and the other a Bride?

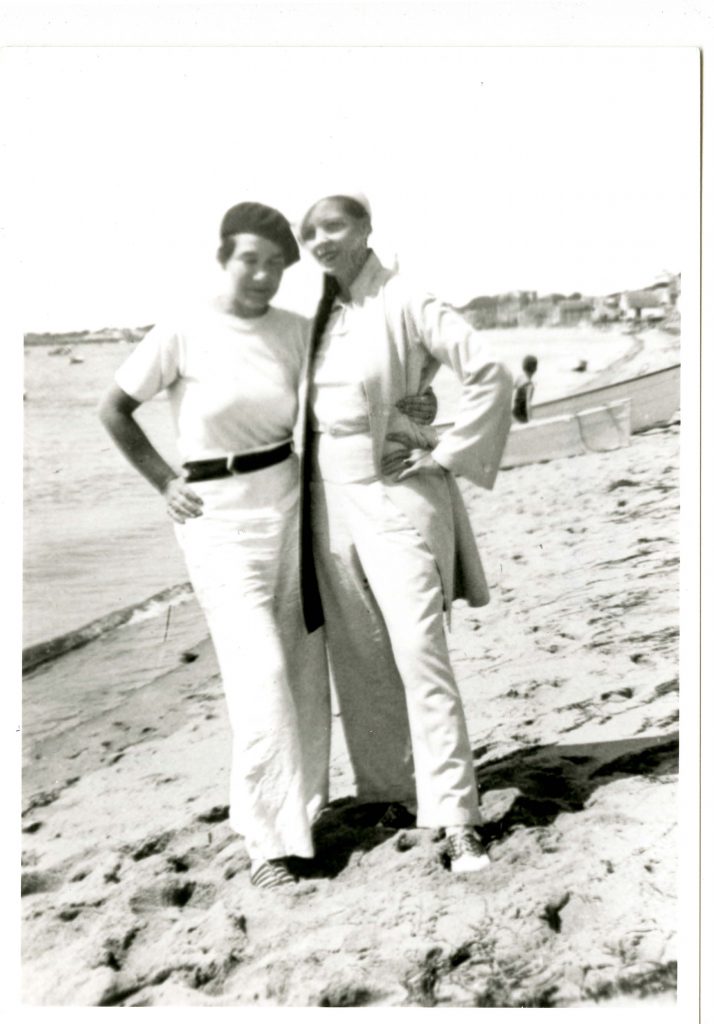

Although Barnes was clearly poking fun at the stately yet fumbling Hall and Troubridge and their traditional ideals, this passage nonetheless marks a significant moment in lesbian herstory. Nine decades before the legalization of same-sex marriage across the USA and the UK, Barnes – perhaps unwittingly – proposed a vision of lesbian union that would prove to be both prescient and progressive. (Of course, “Gentleman Jack” Anne Lister and Ann Walker had secretly cemented their relationship by exchanging rings and taking the Communion together almost a century before the publication of Barnes’s Almanack.)

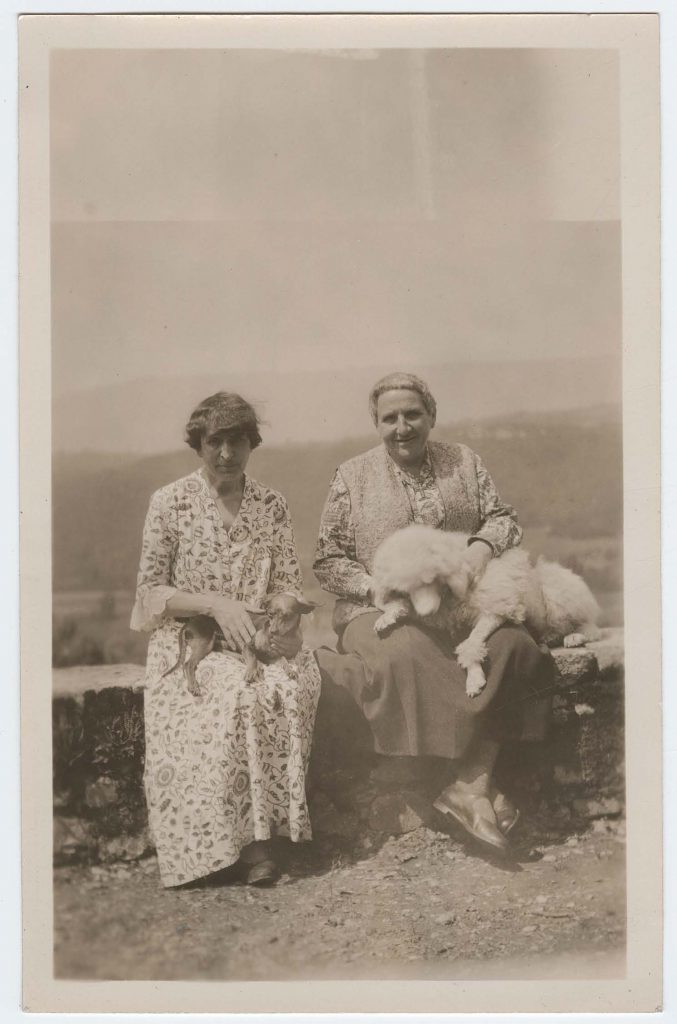

The Outside Thing: Modernist Lesbian Romance explores marriage narratives in the lives and works of three significant twentieth-century women writers: Radclyffe Hall, Djuna Barnes, and the ever-experimental Gertrude Stein, famously “hubby” to “blessed baby wifey” Alice B. Toklas. My book discusses ways in which subversive lesbian writers stretched the limits and genre expectations of the Victorian romance plot, at once adopting and interrogating its stock ending in either marriage or death. Stein’s first novel Q.E.D. (written in 1903, published in 1950 as Things As They Are) is a roman à clef based on Stein’s early romance with a woman called May Bookstaver – whose very name, as the text makes clear, is bound up with both uncertainty (“May be”) and “storybooks.” The novel ends in a situation that “comes very near being a dead-lock,” with Stein’s linguistic play placing her characters symbolically between death and wedlock. Hall’s The Well of Loneliness concludes with Mary’s proposed engagement to Martin and the straightforward observation that “Stephen Gordon was dead; she had died last night; ‘A l’heure de notre mort.’” Even Barnes’s Nightwood (1936), a complex and often macabre modernist novel that depicts desperately unhappy relationships between women – Robin Vote feels “the tragic longing to be kept,” while Nora Flood “knew that there was no way but death” – ends with its two heroines reunited in a chapel.

At a time when lesbian couples are living the marriage plot on both sides of the Atlantic, The Outside Thing asks not only that we reassess the genre identity of lesbian fictions but also that we pay closer attention to literary modernism’s popular heritage and engagement with tradition. Equal marriage may not have been a possibility when Hall wrote The Well’s wedding scenes – and, over ninety years later, religious ceremonies like Adèle and Jean’s may still be off limits – but lesbian writers clearly had their way with the “straight” spaces of linear romance plots.

Explore more from our Valentine’s Day features and save 30% on this or any of our other books on our website when you use coupon code: CUP30 at checkout.