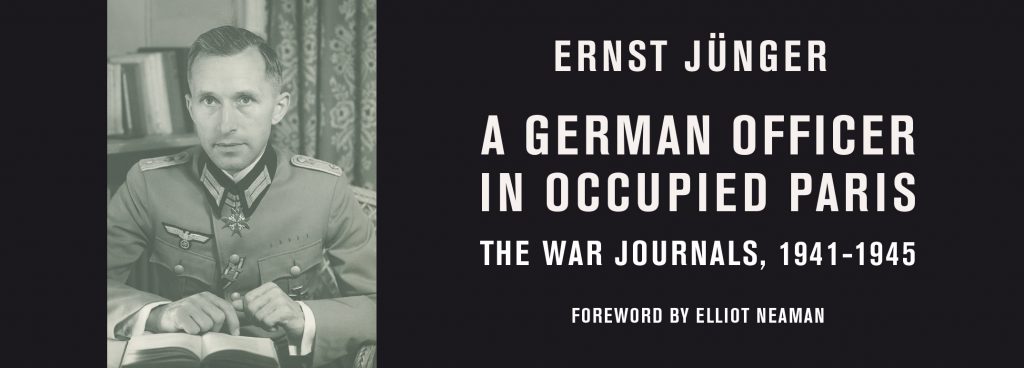

Thomas Hansen on Translating Ernst Jünger

“Ernst Jünger’s record of German-occupied Paris and the battlefields of the Caucasus is a treasure trove for readers interested in the history of the Second World War. Even more, though, it is a literary accomplishment of the first order, a document of European modernism, in which this master stylist leaves traces of the violence of the age between the lines of his crystalline prose.”

~ Russell A. Berman, Walter A. Haas Professor in the Humanities, Stanford University, and senior fellow, Hoover Institution

Welcome back to National Translation Month! This week, we’re looking at different perspectives on World War II and its aftermath. One particularly fascinating and complicated perspective can be found in the journals of Ernst Jünger, newly published in translation as A German Officer in Occupied Paris: The War Journals, 1941-1945. Jünger worked as a mail censor, observed the atrocities of the eastern front, philosophized about the politics of collaboration, met prominent French artists, worked alongside officers plotting to assassinate Hitler, and eventually reunited with his family. In today’s guest post, translator Thomas Hansen comments on his process translating an excerpt from Jünger’s journals that describes an air raid.

• • • • • •

When we undertook this translation, we had not anticipated the complexities that Jünger’s German text presented. He frequently uses long, hypotactic clauses with subordinate constructions that cannot be represented by English relative clauses and still be intelligible. This meant that in places we had to find judicious ways to paraphrase Jünger and still remain true to his message. The prose of this well-read and widely published soldier-writer surprised us—as it has so many English-speaking readers—with its emotional range, clarity of description, and honesty of analysis. At the same time, his mystical dream accounts and preference for euphemism or allusion can produce passages of considerable density that an English translation is obligated to clarify.

The following passage demonstrates how Jünger could balance the aesthetic and the ethical sides of mechanized warfare:

On September 15, 1943, Jünger observes allied bombers over the outskirts of Paris:

English Translation:

I was eating alone in my room in the Raphael when the air raid sirens sounded at approximately twenty minutes to eight. The sound of intense cannon barrage soon erupted; I hurried up to the roof. The scene presented a display that was both terrifying and magnificent to my eyes. Two great squadrons were flying in wedge formation over the center of the city from northwest to southeast. They had apparently already dropped their payloads, for broad swathes of smoke clouds towered to the heavens from the direction they had come. The sight was ominous, but the mind immediately grasped that in that area hundreds, perhaps thousands of people were now suffocating, burning, and bleeding to death.

In front of this leaden curtain lay the city in the golden twilight. The rays of the setting sun glinted on the underside of the aircraft; their fuselages contrasted with the blue sky like silverfish. The tailfins in particular focused and reflected the rays as they shone like beacons.

These squadrons moved in formation like flights of cranes, shimmering at low altitude over the cityscape while groups of little white and dark clouds accompanied them. I watched the points of fire—focused and tiny as pinheads—gradually melt and spread out into burning orbs. Occasionally, a flaming plane would drift slowly downward like a golden fireball without leaving a trail of smoke. One of them plummeted in darkness, spinning to the ground like an autumn leaf, leaving only a trace of white smoke behind. Yet another was torn apart as it plunged, leaving a huge wing hovering in the air. Something of considerable size, sepia-brown, gathered speed as it fell—most likely a man attached to a smoldering parachute.

German Original:

Im »Raphael» aß ich auf meinem Zimmer, als etwa zwanzig Minuten vor acht die Sirenen Alarm kündeten. Bald ertönte lebhaftes Feuer; ich elite auf das Dach. Dort eröffnete sich den Augen ein zugleich furchtbares und großartiges Bild. Zwei starke Geschwader überflogen in Keilform von Nordwesten nach Südosten die innenstadt. Sie hatten offenbar schon schon abgeworfen, denn in der Richtung aus der sie kamen, erhoben sich in breiter Ausdehnung Rauchwolken, die bis zum Firmament hinaufragten. Der Anblick war unheilvoll und machte sogleich den Sinnen deutlich, daß dort jetzt Hunderte, ja vielleicht Tausende von Menschen erstickten, verbrannten, verbluteten.

Vor diesem düsteren Vorhang lag die Stadt im goldenen Lichte des Sonnenuntergangs. Die Abendröte traf die Flugzeuge von unten; die Rümpfe hoben sich wie Silberfische vom blauen Himmel ab. Besonders die Schwanzflossen schienen die Strahlen aufzufangen und zu sammeln; sie glänzten wie Leuchtkugeln.

Diese Geschwader zogen im Kranichsfluge, schimmernd, in geringer Höhe über das Weichbild, während Gruppen von weißen und dunklen Wölkchen sie begleiteten. Man sah die Feuerpunkte, um die sich, erst scharf und winzig wie Nadelköpfe und dann allmählich zerfließend, die Bälle breiteten. Zuweilen stürzte brennend, ganz langsam und ohne rauchende Fahne, als goldene Feuerkugel ein Flugzeug ab. Eins sank auch dunkel, sich kreiselnd drehend wie ein Blatt im Herbst, zu Boden, und dieses ließ eine Spur von weißem Qualm zurück. Wieder ein anderes wurde im Sturz zerrissen, ein großer Flügel schwebte lange in der Luft. Auch etwas Sepiabraunes, Umfangreiches fiel mit wachsender Geschwindigkeit; hier stürtzte wohl ein Mensch am verkohlenden Fallschirm ab.

If you enjoyed this translation, enter our drawing for a chance to win a free copy of the book. Or, save 30% when you order online using coupon code: CUP30!