The 18th Century Poetry of Huimyong, Li Ye, and Lady Kasa

This week, we’ve been featuring works of female poets in translation. On Tuesday, Joshua Fogel shared his experience with Yosano Akiko’s travel writing, and yesterday, Barbara Heldt considered how Karolina Pavlova’s A Double Life took on a new life once it gained a global audience. Today’s post takes us back to the 18th century and features poets from Japan, China, and Korea.

• • • • • •

Throughout the years, we have published many translated works written by female poets spanning various periods and regions. Between the pages of our anthologies and compilations that dot our list, readers can find works published before 1800.

The three poets featured below—one each from China, Japan, and Korea—wrote within a generation of one another, and participated in the literary traditions and genre conventions current in their respective times and places. Together, they represent an infinitesimal fraction of the poetry by premodern women writers.

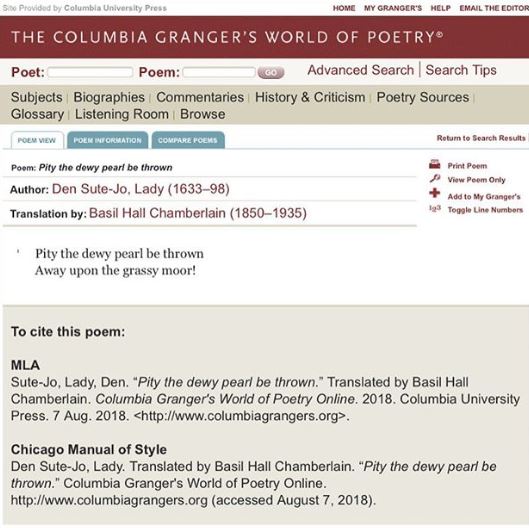

Here are two poems by the nearly anonymous Lady Kasa. These two works come from the Man’yōshū (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves), and so must have been written before its compilation ca. 759. One of the compilers of the collection was Ōtomo no Yakamochi (718? – 785), to whom most of her love poems are addressed; that’s all that is known about her.

Man’yōshū No. 603

If just loving–

if that alone were enough

to make one die–

why, then, I would be dead

by now a thousand times.

Man’yōshū No. 594

Around my house

the light of sunset shimmers

in dew on grasses–

dew that fades as vainly

as do I, for love of you.

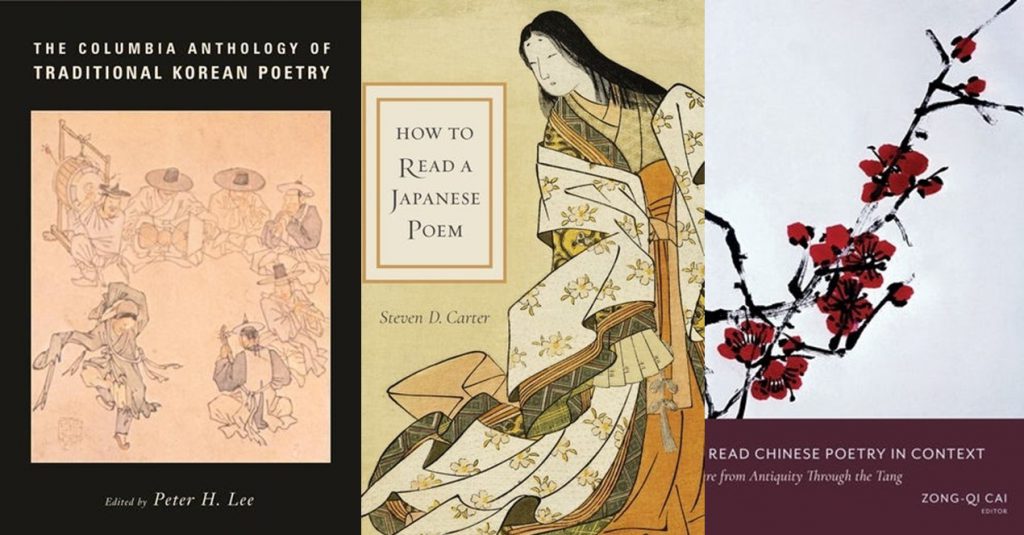

*Lady Kasa (fl. 8th c.), Man’yōshū (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves) Nos. 603 & 594, from Steven D. Carter’s new How to Read a Japanese Poem.

Li Ye, the most famous of the poets discussed here, was a Daoist nun who became well known for her poetry for the Tang imperial court. When the rebel Zhu Ci took the capital in 783, Li Ye wrote a poem to him “so positive in tone it was considered treasonous” after the emperor retook the court the following year, and she was executed for having written it.

My home once lay among the clouds of Mount Wu,

I would often hear the Flowing Springs of that mountain.

The jade zither gradually reaches heights of desolation–

Just like what I used to hear in my dreams.

The Three Gorges are far off, several thousand miles,

Yet all at once they flow into these lonely inner chambers.

Huge rocks, tumbling cliffs, flow from these playing fingers,

Flying rapids, running waves arise from the strings.

At first it seems to be the angry sound of storm and thunder;

Then again, sobbing moans, as if unable to flow–

Swirling whirlpools, eddying rapids, as if expending their last–

And now, again, dripping on smooth sand.

I remember of old when Ruan Ji composed this tune,

Even Zhong Rong could not hear it enough.

Play it once to the end, then play it again,

I wish we could make these flowing springs go on forever!

Li Ye (d. 784), “Attending Xiao Shuzi while Listening to the Zither; the Topic Assigned to Me Was “‘Song on the Flowering Springs near the Three Gorges,’” from How to Read Chinese Poetry in Context: Poetic Culture from Antiquity Through the Tang, ed. Zong-qi Cai.

Huimyong’s Hymn to the Thousand-Eyed Sound Observer was written as a prayer for the author’s son to recite at a temple. It belongs to the genre of hyangga, songs in Korean rather than classical Chinese poetry, most of which follow the format here: two stanzas of four lines plus a two-line conclusion. Like many hyangga, too, Huimyong’s song has some Buddhist content: the text’s “Thousand-Eyed Sound Observer.”

Falling on my knees,

Pressing my hands together,

Thousand-Eyed Sound Observer,

I implore thee.

Yield me,

Who lacks,

One among your thousand eyes;

By your mystery restore me whole.

If you grant me one of your many eyes,

Oh, the bounty, then, of your charity.

Huimyong (fl. 742-765), “Hymn to the Thousand-Eyed Sound Observer,” from The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Korean Poetry, ed. Peter Le

Fill your collection with works by talented women in translation by taking advantage of our WITMonth sale! Check our website for the complete list of promotional titles and use coupon code WIT2019 at checkout to save 30% on your order.

Categories:Book ExcerptTranslationWomen in Translation

Tags:How to Read a Japanese PoemHow to Read Chinese Poetry in ContextHuimyongHymn to the Thousand-Eyed Sound ObserverLady KasaLi YePoetryPoetry in translationSteven D. CarterThe Columbia Anthology of Traditional Korean PoetryWITMonthWITMonth19WITMonth19Week1