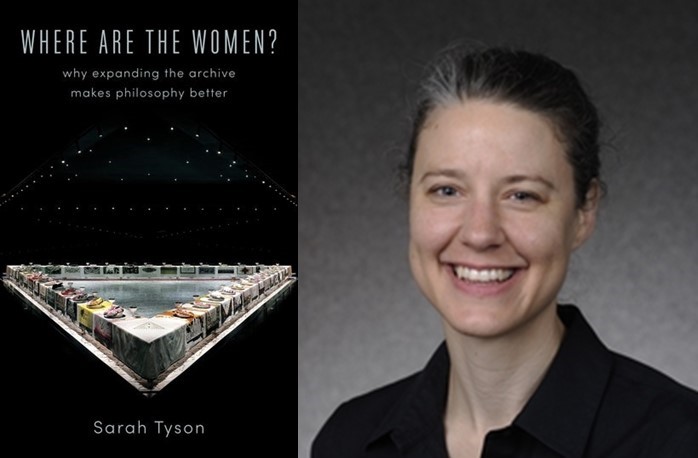

Q&A: Sarah Tyson on Where Are the Women?: Why Expanding the Archive Makes Philosophy Better

“In this bold book, Sarah Tyson revamps the feminist reclamation project to redress not merely exclusion, but all manners of exclusive inclusion. Whether you have never thought of, are inclined not to think of, or are enthusiastic about the thought of Sojourner Truth in the same philosophical frame as Diotima or Socrates, you should read this book.”

~ David Kazanjian, author of The Brink of Freedom: Improvising Life in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

It’s the final week of Women’s History Month, and we’re asking “Where Are the Women?” Philosophy has not just excluded women, it has also been shaped by the exclusion of women. In her new book, Where Are the Women? Why Expanding the Archive Makes Philosophy Better Sarah Tyson makes a powerful case for how redressing women’s exclusion can make philosophy better. In today’s interview, Tyson explains her persuasive writing technique of utilizing speculative, thought-provoking questions that engage the past, present, and future of women’s rights, feminism, and racial equality. She also encourages the reader to engage daily with self-inquiry, as it is a way to not only expand societal norms but also to reconsider such “inherited events” like, for example, the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.

For a chance to win a copy of this book, enter this month’s drawing!

• • • • • •

Q: In your book you speculate about historical events, such as the meeting in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York that produced the Declaration of Sentiments and is often considered the start of the US Women’s Rights Movement. For instance, you ask: what if women had gotten the vote in 1848, when it was proposed in the Declaration of Sentiments? Isn’t this type of speculation more a technique of fiction writing than of philosophy? What do you hope to achieve with this method?

Sarah Tyson: While it is a technique of fiction, I also found it a helpful way to illuminate what happened historically and how we have inherited events. The French philosopher Michele Le Doeuff led me to think about history in this way, which is the focus of the fourth chapter of my book. What if women were considered full citizens in 1848? Rather than imagining specific events that could have occurred, as a fiction writer might, in the book, I ask questions such as: What does it mean that we are the inheritors of a political system in which women’s suffrage actually took another 70 years? What does it mean that, at that point and for a long time after, suffrage really only extended to white women?

Q: On that point, does this technique of speculation help us think about the contemporary tensions between racial equality and feminism?

ST: I think it can help us see how there came to be tensions between racial equality and feminism and why those tensions have taken their specific forms. That is, I think listening in a speculative fashion to an orator such as the itinerant preacher and former slave Sojourner Truth speak to women’s rights advocates helps us hear that she did not think equal rights for women were possible without racial equality. With a speculative technique, I think Truth’s speech in Akron, Ohio in 1851 appears much more radical than we have tended to think. Usually, it is remembered for a line she likely did not speak: “Ain’t I a Woman?” Such a question, as I argue, reduces her intervention to an insistence that Black women are women, too. Truth was doing so much more than that story suggests; her goal was not so much to open up the category of womanhood to Black women (as is popularly suggested), but rather to destabilize the meaning of women’s rights in order to invite her audience to think with her what freedom might entail, including the upending of the current social order. A speculative approach helps us appreciate the work of someone such as the historian Nell Painter, who has not only told Truth’s more radical story, but who has also consistently been met with disbelief by those attached to the more anodyne version of events. To be clear, I was one of those people with such attachments before taking seriously this speculative project.

Q: Does it matter if philosophy expands its canon? And does it only matter to philosophers?

ST: How we tell the history of philosophy matters for how we think. That is, philosophy can be a powerful practice of questioning our quotidian ways of being and doing. This can result in important self-inquiry; but, it can also have the pernicious result of rationalizing structures of oppression and domination. And that reinforcement can have important effects far beyond philosophy. I argue that in the effort to be wary of this second outcome, we should resist establishing a canon. I encourage practitioners of philosophy to consider that, every time we write a syllabus or a book or deliver a lecture, we think of ourselves as constructing a historical narrative about philosophy, however muted or implicit. But my broader point is that philosophy is happening in many places and at many times that are hard to recognize according to prevailing disciplinary norms. I think that taking the philosophical work happening in peoples’ everyday lives seriously can be transformative, not just for professional philosophy, but for our lives and for the structures that determine the limits and possibilities of our lives.