A Reluctant Translator: Reflections from John Nathan

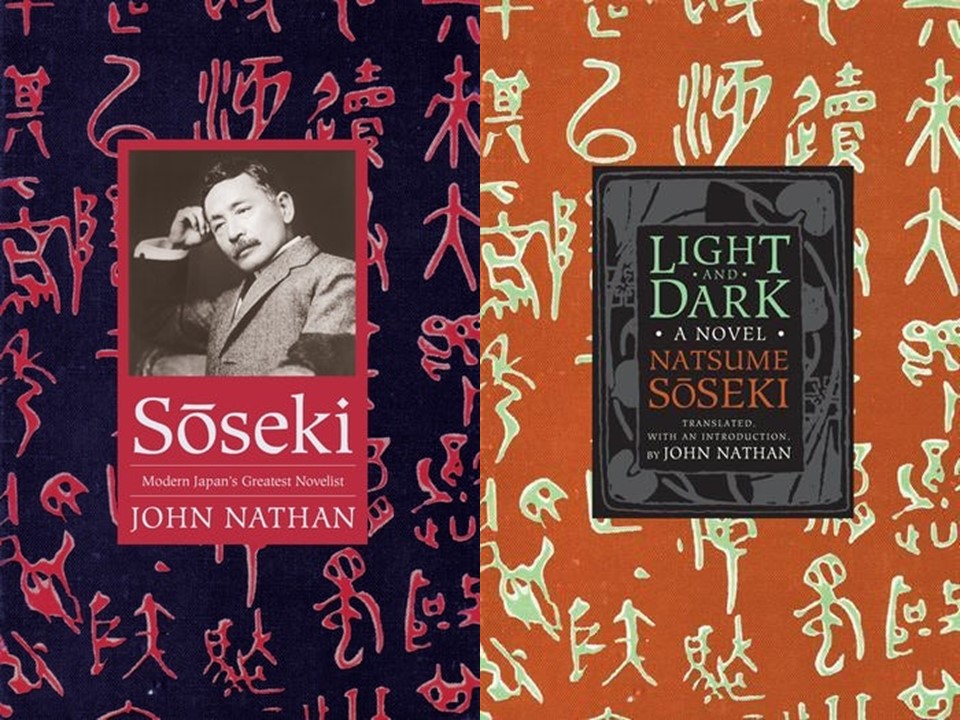

As part of our month-long feature celebrating National Translation Month, today we have a guest post by John Nathan, author of Sōseki: Modern Japan’s Greatest Novelist and translator of Natsume Sōseki’s final novel Light and Dark.

Remember to enter our drawing for a chance to win one of this weeks featured titles!

• • • • • •

For nigh on sixty years, I have been an unfaithful translator. Not to texts so much, but to authors. Had I adhered loyally to one or another of the major novelists I rendered, accounting in English for a significant portion of an oeuvre, I might have earned myself a seat at the table of literary history along with fabled translators such as Constance Garnett, Scott-Moncrieff or, more recently, the unstoppable Pevear/Volokhonsky team. But for me it was always less a matter of the author than a specific work: reading in the Japanese original I had to feel smitten, unable to bear the thought that Anglophone readers should be deprived of access to such a wondrous piece of writing, to commit to a translation.

“Reading in the Japanese original I had to feel smitten, unable to bear the thought that Anglophone readers should be deprived of access to such a wondrous piece of writing, to commit to a translation.”

I can’t say, looking back, that I was enthralled by the first novel I translated, Yukio Mishima’s 1963 The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea. I was aware that I was working on a slick entertainment, a vintage Mishima interweaving of eros and death. But The Sailor wasn’t my choice; it was a project awarded to me by the editor in chief of Alfred Knopf, Harold Strauss, in Japan to find a new Mishima translator. Twenty-three at the time, untried, I had been obliged to audition for the job, first with an interview by Mishima himself (at the Taishō era French restaurant, Le Crescent), and then with a sample translation of the first chapter. Two weeks after I mailed my draft translation to New York, my landlady came shuffling down the corridor to my room and announced in wide-eyed excitement that Yukio Mishima was on the phone–he was calling to congratulate me. I laid out three hundred dollars I couldn’t afford for a Mont-Blanc fountain pen, the stubby cigar-style writing instrument of choice for all important Japanese novelists including Mishima. Working every night from midnight to dawn as Mishima did, I reveled in the feeling that I had been acknowledged by the grown-ups as a young man of letters.

My translation of The Sailor was favorably received in the U.S. and in Europe. One night in Tokyo, at the Japanese restaurant Hamasaku on the Ginza, Mishima presented me a copy of his 1964 novel, Silk and Insight, and asked me to translate it, assuring me that we were an “unbeatable team.” Coming from the most famous novelist in the land, this was a heady request. I read the novel dutifully and found it rank as a greenhouse. Besides, I had already been bowled over by the virulent imagination that powered Kenzaburo Ōe’s latest novel, A Personal Matter. Harold Strauss urged me to stick with Mishima, who was rumored to be in line for the Nobel Prize, but I was too far gone to heed him (in fact it was Ōe who would win in 1994). Mishima was angered by my shift in allegiance and I never saw him again. Strauss finally agreed to publish Ōe if I insisted, but Ōe’s admiration for Barney Rosset, one of his American heroes, inclined him toward Grove Press and that is where we took the book. When A Personal Matter was published in May, 1968, Rosset, determined to attract attention to a novel by a then unknown Japanese writer, flew Ōe to New York and arranged for interviews with the entire community of reviewers. Every day for two weeks, Ōe and I ordered eggs benedict at a different restaurant (Sardi’s East served the best) and beguiled critics with a vaudeville act designed to highlight Ōe’s stunning command of Western literature. Our efforts were rewarded most gratifyingly in Eliot Fremont Smith’s effusion in The New York Times that A Personal Matter was “something very close to a perfect contemporary novel.”

“Had I adhered loyally to one or another of the major novelists I rendered . . . I might have earned myself a seat at the table of literary history.”

I continued to translate Ōe, but intermittently. In 1977, in Jamaica with Barney Rossett and our families, I began work on a collection of Ōe’s best novellas to date, including my retranslation of “Prize Stock” (the original English title was “The Catch”), the 1959 story of a black American pilot shot down over an isolated village in the mountains of Shikoku that had won for Ōe the Akutagawa Prize, then as now the gateway to consideration as a serious writer, while he was still a college student. I loved all four selections in the collection, published by Grove as Teach Us To Outgrow Our Madness, but I considered “Prize Stock” above all, in which Ōe returned for the first of countless times to the mythical homeland in his imagination, the most brilliant story produced in postwar Japan.

In Stockholm for Ōe’s Nobel Prize in 1994, carried away by the excitement, I contracted with Grove Press to translate at least two of five undesignated Ōe novels and to “oversee” the others. It was foolish of me to imagine in the heat of the moment that I was finally ready to content myself with life as a dedicated translator: it wasn’t until 1999, five years after Stockholm, that I sat down to translate another Ōe novel, Rouse Up O Young Men of the New Age!, a chronicle at once heart-rending and uplifting of the relationship between a father and his retarded twenty-year old son mediated by the poetry of William Blake. I haven’t translated Ōe since. Although he never said anything to me directly, I know that my meager output frustrated him. Rosset showed me a letter he had received in which Ōe complained that I was wasting my time making movies and appearing on the Japanese stage. “I hope Nathan will recover his diligence as a translator,” he wrote in English.

“I had been teaching Japanese literature for fifty years and confess I had never read [Light and Dark]; I knew about it only that it was unfinished, interrupted by Sōseki’s death in December, 1916.”

In the spring of 2011, I happened to take down from the bookshelf Sōseki Natsume’s novel Meian (Light and Dark). I had been teaching Japanese literature for fifty years and confess I had never read Meian; I knew about it only that it was unfinished, interrupted by Sōseki’s death in December, 1916. It was a thick volume, 640 pages, and I began reading idly enough, not expecting to read all the way through. But the very first scene intrigued me—an arresting opening for a novel, the diagnosis of an anal fissure—and I read on to see where it would lead, and every few pages I scribbled in a notebook, “a (Henry) Jamesian moment!” It took me two weeks to reach the end, and when I had finished I felt certain that Meian was the first “modern” Japanese novel in the Western sense of the term that I had ever read.

Reading Meian was a familiar experience, recalling for me how I had felt about Ōe’s A Personal Matter fifty years earlier: it simply wouldn’t do to deprive foreign readers of the pleasure Sōseki’s masterpiece afforded in the original. But this time I was conflicted; I didn’t want to mire myself in the struggle this would entail. I had paid my translator’s dues, and I had my own fiction to write. Besides, I knew that an English translation already existed. In the university library I found V. H Viglielmo’s 1972 translation, Light and Darkness, and I opened it in trepidation, wanting, honestly wanting, to find it excellent or at the very least adequate. But it was apparent to me from the opening pages that the translation failed to capture the complex music of Meian. My heart sank, and at the same time I was relieved and elated in a familiar way.

“I have promised myself that Light and Dark will be my last translation. But who knows, even an old man can fall in love again.”

I labored over the translation for over a year. To create the patina of age that a novel written over 100 years ago would have acquired for the native reader, I had recourse to Henry James, harvesting from his pages words and turns of phrase that struck me as redolent of the period in which Sōseki’s novel is set. I have promised myself that Light and Dark will be my last translation. But who knows, even an old man can fall in love again.

• • • • • •

Read an excerpt from John Nathan’s new biography of Natsume Sōseki, Sōseki: Modern Japan’s Greatest Novelist.

Read the beginning of Sōseki’s final novel Light and Dark, translated by John Nathan.