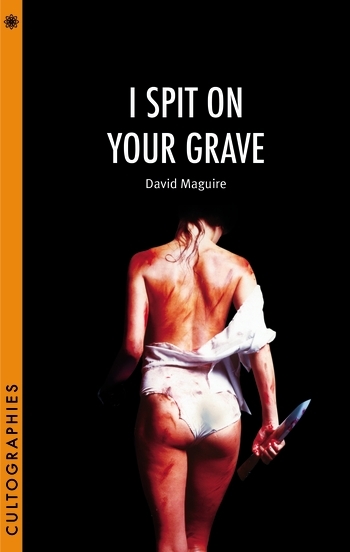

I Spit On Your Grave: From Celluloid Pariah to Cult Film

This week, our featured book is I Spit on Your Grave. Today, we are happy to present an guest post from author David Maguire!

Enter our book giveaway by 1 PM today for a chance to win a free copy!

• • • • • •

From its unflinching subject matter (the brutal gang-rape of a beautiful career woman and her subsequent revenge), its battles with censors and mauling by critics, the picketing of its screenings by feminists and the politicians who deemed it a corrupting influence on society, I Spit On Your Grave (1978) is a film that continues to divide opinion and inflame passions. It is, depending on your point of view, either one of the most powerful or disturbing rape revenge films ever made. While many condemn its misogyny, others praise it for raising uncomfortable issues about sexual violence, then unheard of in exploitation – or even mainstream – movies. It is deeply distressing to watch – it was in 1978 and remains so today. And yet that is not to say that it is a bad film without merit, only that the film’s reception was, and continues to be, complicated.

To fully understand the film’s growth from celluloid pariah to cult film, one has to explore its unique position in, and impact on, the cultural, historical, political and gender landscape of its initial release. While other exploitation films of the 1970s/1980s and the UK ‘video nasties’ scandal have been consigned (often quite rightly) to the trashcan of time, I Spit On Your Grave has found itself mythologized and revered by the countless rape-revenge films that have followed. Despite almost universal condemnation, director Meir Zarchi’s film has spawned official and unofficial franchises, and even a spoof. Cynics may argue that these productions are simply ‘cashing in’ on the cultural memory of the original, and there is undoubtedly an element of this, but there is also evidence to suggest that I Spit On Your Grave is being updated to explore more complex issues such as vengeance and retaliation in a post-9/11 world relating to the ‘war on terror’. The film’s official remake and sequels challenge contemporary viewers in different ways to the original, questioning ideological and ethical issues relating to torture, revenge and violence.

In light of its impact on film culture and the increasing number of pro-feminist reappraisals of the film – something which is in itself problematic in light of the clear exploitation route the movie went down and the (male) audience such productions are designed to appeal to – it is perhaps fitting that, 40 years on, Zarchi’s film is re-examined as an important part of cinema. While other challenging independent horrors of the era such as Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Last House on the Left (1972) and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) have all since been re-evaluated and acclaimed (with the latter added to the permanent collection of New York City’s Museum of Modern Art), I Spit On Your Grave is still very much brushed under the carpet in most circles. But just as these once vilified films are now regarded as having something important to say about society, I Spit On Your Grave is no exception. It can be argued that Zarchi’s insistence on tackling rape in the manner that he does is a key reason why many continue to find the film so repulsive.

While its remakes and sequels have helped contribute to turning the film into a cult movie, its imitators – of which there are many – remind us of just how creative, daring and provocative the original was. I Spit On Your Grave does not need to rely on over-blown non-diegetic music to prompt the viewer how to feel (The Accused [1988]). It does not need to introduce clichéd supporting characters like sympathetic (male) detectives to strengthen identification with its protagonist (Naked Vengeance [1985], Thelma & Louise [1991) and The Brave One [2007]). It can also be argued that it doesn’t utilize models for its heroine, thereby eroticising her subsequent rape (e.g. Raquel Welch in Hannie Caulder [1971], Margaux Hemingway in Lipstick [1976]). While Camille Keaton, playing Zarchi’s central character, is an attractive actress and is coded as such, it is difficult to argue that the film’s rape scenes are titillating; if anything, they are represented in such a realistic grotesque manner that Hollywood would never go near.

And yet, because it has been marketed as exploitation, many have been unable to see past this label and have failed to realize that herein lies a genuinely shocking film – but not for the reasons that have seen it pilloried, censored, banned and condemned. It is important to remember that from being part of the narrative in earlier films, ISOYG has been instrumental in making rape-revenge the narrative. And unlike the eroticised route down which most rape-avengers strut, both the 1978 film and its 2010 remake have attempted to make serious comments about sexual violence. However, the main area of conflict has been generated by those who find it difficult to marry these films’ supposedly anti-patriarchal sentiments with a genre that has traditionally overflowed with gratuitous images of sexually exploited women. And while Zarchi and Stephen R. Monroe (the remake’s director) may claim to have come to their projects with noble intentions, these have had to be juggled with the expectations of their intended audiences; Zarchi’s the grindhouse circuit and unregulated home video market, Monroe’s the post-9/11 torture porn crowd with an appetite for elaborate retaliation. Understandably this duality has caused friction with many denying that any such picture can seriously be considered pro-feminist.