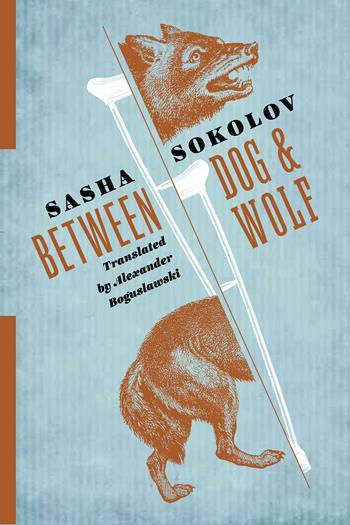

Excerpt from Sasha Sokolov's Between Dog and Wolf

This post is a part of the inaugural week of the Russian Library, a new series that seeks to demonstrate the breadth, variety, and global importance of the Russian literary tradition to English-language readership through new and revised translations of premodern, modern, and contemporary Russian literature.

Enter the Russian Library Book Giveaway here

This excerpt from Chapter 5 finds one of the principal characters, the erudite poet-philosopher Yakov Ilyich Palamakhterov, reveling in scholarly company at a publishing meeting-turned-party. Uncomfortable in his own skin, his social blunders launch the narration into recollection of awkward episodes past. This passage is the reader’s first formal introduction to Yakov and his interiority.

“And God only knows how long their confusion would have lasted if the porter Avdey, a sleepy peasant with a pitch-black beard reaching up to his dull and birdlike tiny eyes and with a similarly dull metal badge, did not come to say to the master that they should not be angry—the samovar completely broke and that is why there will be no tea, but, say, if needed, there is plenty of fresh beer, brought on a pledge from the cabbie, one should only procure a deed of purchase, and if in addition to beer they had wished to have some singing girls, they should send a courier to the Yar right away. Eh, brother, You are, methinks, not a total oaf, the policeman addresses the sentinel—and soon the table cannot be recognized. The prints and typesets are gone. In their place stand three mugs with beer, being filled, in keeping with their depletion, from a medium-size barrel that, with obvious importance, towers above the modest, but not lacking in refinement, selection of dishes: oysters; some anchovies; about a pound and a half of unpressed caviar; sturgeon’s spine—not tzimmes but also not to be called bad; and about three dozen lobsters. The Gypsies are late. Waiting for them, the companions arranged a game of lotto, and none else but Ksenofont Ardalyonych shouts out the numbers. Seventy-seven, he shouts out. A match made in heaven, rhymes Palamakhterov, even though he has no match. Forty-two! We have that too, the man from Petersburg assures, although again his numbers do not correspond. Deception of Nikodim Yermolaich is as petty as it is obvious, and as outsiders we are quite embarrassed for him; but the pretending of Yakov Ilyich stands out black on white. Possessing from his birth the enchanting gift of artistic contemplation, but being both shy and frail, now and then he tried not to attract attention to the fact that he was the one whom he, naturally, simply was not able not to be, since he possessed what he possessed. For that reason, probably, Yakov Ilyich’s attempts turned into complete blunders and consequently led not to the desirable but to undesirable results, again and again drawing to the gifted youngster uninterrupted, although not always favorable attention of the crowd. Do you remember how once, long ago, he let his mind wander, and a gust of the April chiller did not wait with ripping off the skullcap from his proudly carried head? It’s really not important that the street, as ill luck would have it, teeming with concerned well-wishers, kept admonishing the hero, warning: Pick it up, you will catch a cold! Ostentatiously ignoring the shouts, taking care not to look back, and arrogantly not stopping but turning the pedals forward and—cynically and flippantly chirring with the spokes, the chain, and the cog of free wheel—backward, attempting to present everything as if he had nothing to do with it, he continued riding, the way he definitely wanted it to be seen through the eyes of the side spectator, with melancholic detachment. But, you know, a certain superfluous stooping that unexpectedly for an instant appeared in the entire subtle look of the courier (exactly like his great-grandfather, his grandfather used to say), diminished, even nullified his efforts to make his bodily movements carefree, froze them, made them childishly angular and exposed the daydreaming errand boy, with his feeble straight-haired head, to the curses of the mob: Scatterbrain, dimwit—the street carped and hooted. And if it were, let us suppose, not simply a slouching chirring courier but a real humpbacked cricket from Patagonia, then, with such a mediocre ability not to attract attention, it would have been immediately pecked apart. But, fortunately, it was precisely a courier—a messenger-thinker, a painter-runner, an artist-carrier, and the nagging feeling that everything in our inexplicable here takes place and exists only supposedly did not leave him that evening even for a moment. That is how, either absentmindedly looking through the window or paging in the diffused light of a smoldering lamp through Carus Sterne—once respectable and solid, but now thinned, reduced by smoking and bodily urges, and yet, even now adequately representing the sole volume of this modest home library—Yakov Ilyich Palamakhterov, the incorruptible witness and whipper-in of his practical and unforgiving time, philosophized and speculated.”

1 Response