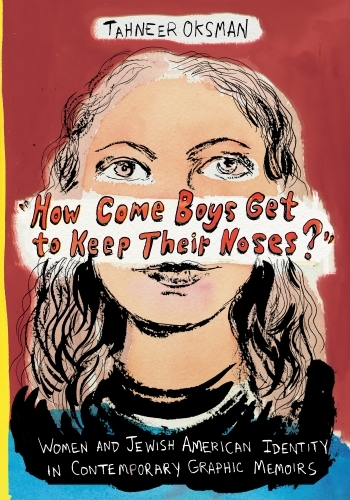

Tahneer Oksman on Writing a Jewish Book

“Why did I write a Jewish book? Because I was trying to reclaim my Jewish self, however unfamiliar its now ragged shape.”—Tahneer Oksman, author of “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?”

When Tahneer Oksman, author of “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?”: Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs, first began as PhD. student in literature, focusing on Jewish women’s comics was not on the horizon As she explains in a recent essay in Lilith, while women’s literature was of great interest to her, she had decided to put her Jewish upbringing behind her:

Somewhere between my upbringing in a Modern Orthodox Jewish day school in the Bronx, and the years of slowly replacing that orthodoxy with new modes of belief and practice — feminism, writing, literature and, yes, yoga — I decided that my Jewish history would never figure, could never figure, in my life as it — as I — had been remade. It would certainly never become a centerpiece.

However, as she pursued her studies, she found herself drawn to the lives of such Jewish writers as Anzia Yezierska, Sara Smolinsky, and Grace Paley. This shift to concentrating Jewish women writers was not necessarily the best career move. Oksman explains:

Writing about a Jewish topic also meant transforming myself into the very worst thing you could become as a graduate student: unmarketable. I was now too Jewish for English Literature programs, and I would never be Jewish enough for jobs in Jewish programs. This left me, as usual, between worlds; if you write your first book on a Jewish topic, after all, you’ve pigeonholed yourself: you’re a Jewish writer. Haven’t you seen how so many of those popular “canonical” Jewish writers (and actors, and painters, and critics) reject that title? Write about something else; take the word Jewish out of your title, for heaven’s sake!

Oksman’s book “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Nose?”, of course, has not only been a critical and scholarly success but also allowed her to explore her own relationship to Judaism:

While I still admit to a heavy dose of cynicism when it comes to almost all modes of exposing and expressing my Jewish self — we’ve let our synagogue membership go, having attended only one service (very briefly), and my husband and I actively considered adopting a Christmas tree this year, despite our both having been raised Jewish and despite the hours of therapy both our mothers’ reactions will cost us — there is something, dare I say, cathartic about this embrace of what I once so forcefully rejected. At a certain point, there comes a time when everyone has to face the fact that her career choices are, well, personal. This isn’t to say that, for example, all oncologists grow up having witnessed loved one’s lost battles in the face of cancer, or that television personalities emerge from childhoods spent being silenced, far from the spotlight. But it is inevitable that, if we take a close enough look, the paths that have led us to where we are, however winding, can be traced back to early burgeoning moments, even deeply disguised ones. The scholar of medieval history will, perhaps, be the first to admit this; it’s those of us who feel most naked in researching and writing who we are, where we come from, that are the most active concealers, the most adamant deniers.

Why did I write a Jewish book? Because I was trying to reclaim my Jewish self, however unfamiliar its now ragged shape.