Colin Dayan’s Ethics Without Reason

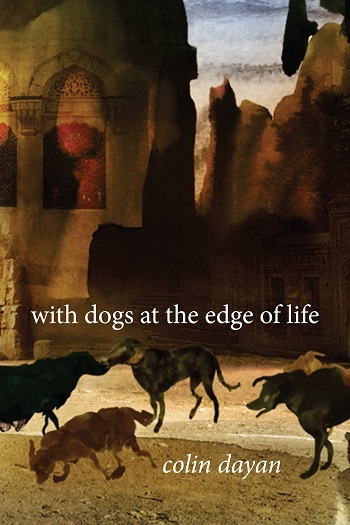

Simon Waxman of the Boston Review recently wrote an excellent reaction/review to With Dogs at the Edge of Life, by Colin Dayan, “Colin Dayan’s Ethics Without Reason.” We have a short excerpt from his article here, and we can’t recommend the full article highly enough.

Colin Dayan’s Ethics Without Reason

By Simon Waxman

Dayan, a longtime friend of Boston Review and valued contributor to the magazine, has explored related matters in our pages before. Her discussions and conclusions are often unsettling, questioning “the pretense of humane treatment” promoted by organizations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and humane societies, which routinely and systematically kills the animals of whom they market themselves as protectors. Dayan also is not a supporter of animal rights, which, like the human equivalents that inspire them, can foster in their bearers the quality most desired by the elites who seek to control and exploit them: docility. Meanwhile, the rights paradigm legalizes punishment of those animals that must be lived with, as opposed to above. In essence, the animal rights agenda has enshrined in law the social acceptability of the dumb, pocket-sized accessory who can only breathe and eat—and, then, only with a human hand to feed it—while subjecting to suspicion and penalty any animal of vigor, independence, intelligence, and, yes, capacity for danger.

Alongside her perhaps-surprising misgivings about rights, Dayan harbors sympathies that many abhor. One chapter of With Dogs at the Edge of Life traces the life, legal struggle, and philosophy of Bob Stevens. A downhome pit bull breeder, Stevens has been prosecuted by the state of Louisiana for distributing dogfighting films and earned the enmity of preening urban pet owners who like to dress up their twelve-pound toys and parade them at parties. These owners lack something that Stevens, for all his hard edges, does not: “admiration and respect for an animal’s sheer bodily strength, fierce intelligence, and courage,” which “promise a reciprocal engagement that has been lost in most human experience.”

…

Dayan’s goal is not just to scrutinize the pieties of animal rights activists, however. Doing so is an element of a larger project in which the boundary between human and non-, between reason and simply being together with other beings, becomes unstable. Following displaced and disdained dogs, purged from increasingly genteel cities everywhere, Dayan pursues a critique of enlightenment itself, particularly that version on which capitalism is founded. “Through the dogs’ eyes, we sense a world devoid of spirit, ravaged of communion,” she writes, inspired by films shot from the standpoint of dogs. These animals who once owned the city alongside human residents are no longer welcome among “the high-rise developments, the spruced-up neighborhoods of the neo-Western globalized citizen.”

There are no answers, easy or hard, in With Dogs at the Edge of Life, and this, finally, may be the point. “The bold enmeshing of humans and dogs—and the seagulls, pigeons, chickens, and cats in their midst—requires that we suspend our beliefs and put aside our craving for final answers.” The answers are themselves the problem. We have—by force, persuasion, and trickery—been drawn to a single answer: money and the comforts it buys. Call it progress in the capitalist mode. The issue of this progress is visible everywhere, from the comfort of killing law never seen in action, to the comfort of gleaming cities devoid of untamed life, to the comfort of faith in a human reason that eradicates all ambiguity and mystery. Indeed, one of the starkest, most material visions of this progress is the puny, slavish body of the dog lived above rather than with.

The full article can be read at the Boston Review website.