The Con Game

“To be honest, I wanted to get some of the cash the man flashed. I had greed in my heart, and that’s what got me into trouble.” — Terry Williams

This week, our featured book is The Con Men: Hustling in New York City, by Terry Williams and Trevor B. Milton. In today’s post, Terry Williams describes his first encounter with a con game in New York, how he was duped, and how this experience led him to study con games in his scholarly work.

Don’t forget to enter our book giveaway for a chance to win a free copy of The Con Men!

The Con Game

By Terry Williams

I first got involved in a con game by chance: I happened to be strolling down the wrong street at the wrong time. However, stumbling into a con made it possible for me to better understand how the con game might be studied in an urban setting.

I was a young student at the time, with only five dollars in my pocket, trying to find my way around the city. On this particular day I became a modern version of Voltaire’s Candide, only instead of finding my fortune I found myself standing on an isolated city street explaining to two strangers why I could be trusted.

Let me go back to the beginning

I saw a man standing near 125th Street. He stopped me to say that he was not from New York (he had an accent), was lost, and needed my help. He showed me a piece of paper, which upon a brief inspection listed an address close to where we were standing, but as I tried to look more closely at the paper, he took it from me and handed it to another passerby with the same question. This time, however, he took out a wad of money and made a generous offer for help finding the address on the paper. He said he had been given $10,000 of insurance money after his brother lost his leg in an accident. He just wanted to “get some pussy before I leave the city.” I didn’t see exactly how much money he had, but it was a big bundle of bills and he said he would give some to both of us if we helped him.

To be honest, I wanted to get some of the cash the man flashed. I had greed in my heart, and that’s what got me into trouble. At this point the other passerby, who of course was a second con man working with the first, said that he knew the address on the paper; in fact, it was just around the corner and down the street. He offered to walk with me to find it. Walking slightly ahead of me, he told me the first guy was a fool for showing so much money. He also said that he would protect me from any bad people in New York City because he could be trusted and would show me that trust.

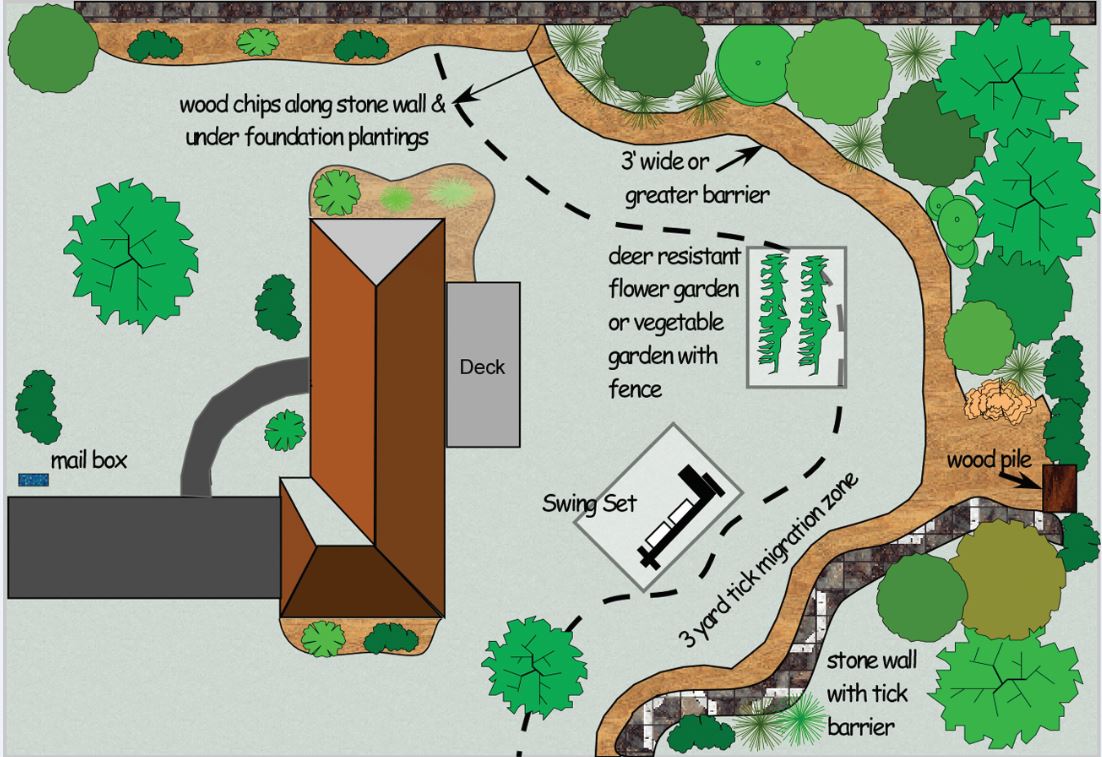

Before I knew it, I was walking on 126th Street, behind the old Apollo Theatre where many of the great rhythm and blues performers hang out between shows, and then I was in a desolate, isolated area with no one around.

I realized later there is a kind of pre-surveillance to the con game: the lay of the land has to be studied and a series of advanced actions must be arranged before a mark is decided upon. As we stood there, my companion asked me if I could be trusted. Of course, I said yes, and he said that he could be trusted too. To prove it, he showed me his wallet with some money in it and asked me to prove my trust by reciprocating and showing him my wallet. At that point he said I should hold all the money in a bag for safe keeping because he trusted me. But, as I put the bag into my pocket, he claimed that that was the wrong way to hold it. “No, let me show you.” He showed me the way the bag should be held, and I did as told. After a few minutes, the original lost man left, supposedly to get the pussy he said he was going to get, and the second man said that he had to go pee. After waiting alone for my companions for an hour, my curiosity got to me and I reached into the bag with the money, only to find a small, wrinkled wallet filled with greenish play money and nothing more.

After this personal experience, I wanted to know more about con games and how they worked. My professor asked us students to write about what he called “ethnomethodology,” a method used to study the everyday activities of people and how what is concealed behind and underneath meaning in conversation is a crucial part of those activities. Around this time I talked to my professor about con games, quite popular in the city at the time, but neither he nor anyone else could explain to me how they worked.

I decided to ask my sister’s boyfriend, who was into thug life and hustling and knew about these types of scams in the city, if he would school me. Though he didn’t admit to being a con man per se, or at least not at first, he gradually expressed an interest. Over time, we did become close enough that I became privy to the con games life and to his methods.

I ended up writing The Con Men: Hustling in New York City, fueled by my curiosity about con games. I realized that in order to be engaged in the con you have to be vulnerable, and to be vulnerable is to take risk; knowing and exploiting this vulnerability is part of the world of the con artist.

I came to realize the importance of architecture, the role that “place” plays in a con as a part of the success or failure of the game. The local ecology such as the weather (rain, snow, sun, etc.) helps determine the particular site of the con, and must be investigated before the con game is actualized.

The moral of the story

The act and the circumstances of the con game represent the ultimate irony and paradox in the sense once expressed by Ricky Jay the Illusionist:

“You wouldn’t want to live in a world where you couldn’t be conned.” His logic is simple, direct, and so brilliant it almost evades you: he said that a world where you cannot be conned would mean “a world where no one could be trusted, not your friend, not your neighbor, not your lover, not your parents, not your government. No one.” The existence of such a world would be devastating to the true tenor of a civil society. As seen in the account recorded above, the essence of the con is trust and trust implies confident belief that another human being will not fail in performance. I think there is a caution here to be aware of these types of noble, general proclamations. Those proclamations are what the con man want you to believe. We do not have to agree or disagree with Ricky Jay the Illusionist, but there is complexity in my tale and in others like it, and the con men can use that kind of complexity in a situation to his advantage because people have to live in the world and they must trust each other.

I have been captivated by the con for many years, and I feel a need to get to the essence of its mystery not only for its own sake but also as a consequence of a need to know as much as possible about what is happening in New York City.