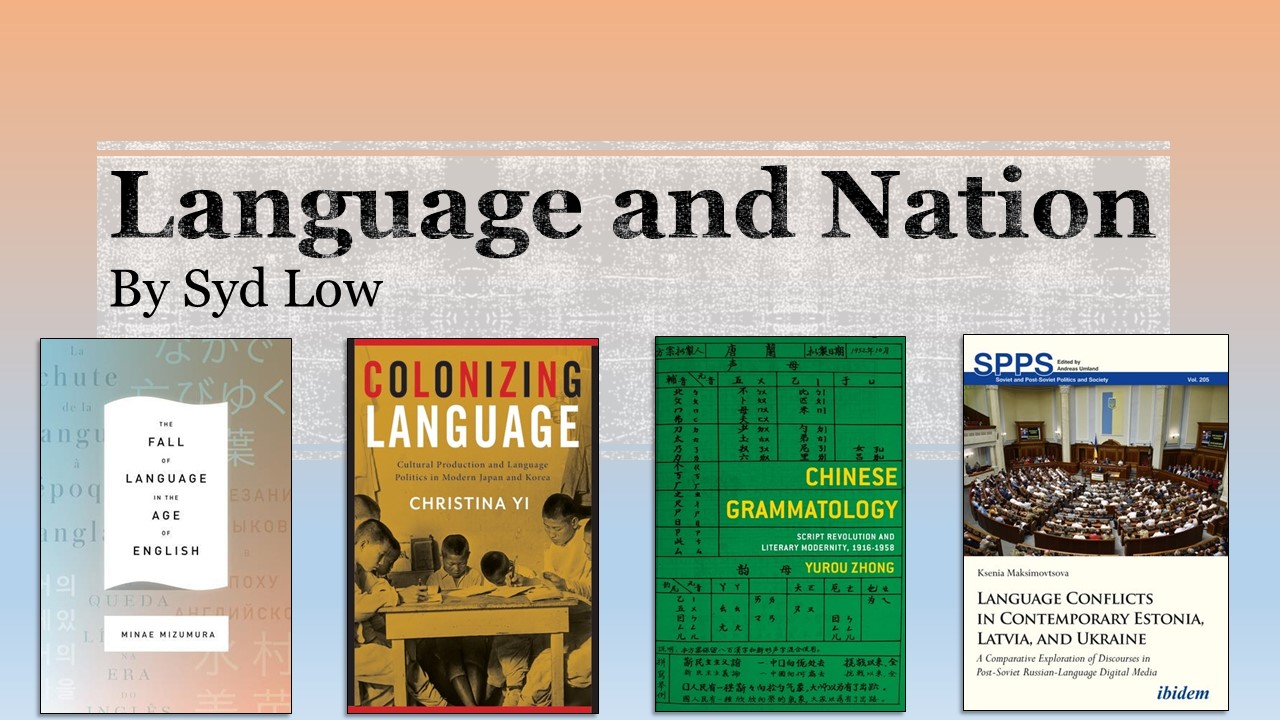

Thursday Fiction Corner — Minae Mizumura As Novelist

Minae Mizumura, author of The Fall of Language in the Age of English is also a well-known novelist. Her most recent novel, A True Novel, is a reimagining of Wuthering Heights and has been widely praised, including a glowing review in the New York Times.

Recently, The White Review, a literary magazine, ran an excerpt from Mizumura’s novel published in Japanese as Shishosetsu from left to right. The unusual title, a mixture of Japanese and English, represents the novel’s content and form. The novel is narrated by a Japanese young woman who, like the author, grew up in the United States in a bilingual environment. ‘Shishosetsu’ refers to a genre of autobiographical novel that characterizes much modern Japanese literature. Since English words and phrases are woven into the text, the novel was written horizontally, from left to right, unlike other Japanese novels, which are written vertically on the page and read from right to left.

THE TELEPHONE RANG AT 9:45 THIS MORNING.

As white morning sunlight poked through the cracks in the blind, I inserted the cord into the telephone jack, digesting the usual sick realisation that another day had begun. No sooner was the telephone plugged in than the ringing gave me a start.

Sudden fear shot through me. It might be the French Department Office.

Is this Minae Mizumura?

Yes it is.

What on earth are you doing?

What on earth was I doing? If they asked me, what could I say? I could not explain it even to myself. I was afraid that somehow the way I was living—holed up in this apartment that remained dim even in the daytime, fearful of the dawning of each new day, for all the world like a snail coiled tightly in its shell—might become shamefully and unmistakably exposed to the light of day.

As hopes of an international call from Tono gradually faded, I fell into the habit of unplugging my telephone every night; apart from the practical desire to avoid being awakened by my sister, the main reason was this very fear.

It is of course a neurotic fear. Every department has one or two delinquent graduate students on its rolls, and there is no reason why the department should care if I put off my orals indefinitely on the pretext that my advisor is in and out of the hospital. It’s not only the department—in the whole huge United States, apart from Nanae hardly anyone is aware that I even exist. And why should they be? Still, I am afraid. From the time I wake up in the morning till five in the evening, when the office closes, I live in fear that at any moment the telephone will ring and I will be given final notice—Your time is up!—and stripped of my identity as a graduate student.

The telephone went on ringing.

Wait. It might be a wrong number, I thought hopefully, someone trying to reach the Social Security Office first thing in the morning. This often happened, as my number was similar to theirs. I reached for the phone, faintly anticipating an old lady’s gravelly voice.

‘Hello? ’

‘Hello. Hi there.’

That voice had already given me an earful. Indeed the voice and my ear had become virtually inseparable. It was Nanae. Along with relief, I felt irritated at her for calling so early in the morning and putting my nerves on edge.

Nanae’s phone calls are never over in a minute or two.

I had been lying on my stomach, propped up on my elbows with the receiver pressed to my ear, but now I flipped over on the mattress so that I was lying flat on my back.

Nanae is a telephone addict. If you added up all the time the two of us spend on the phone together, you would probably reach the logical conclusion that I am no less of an addict, but that is only because she calls so often. After an interval of two days with no communication she will call and ask, ‘Still alive?’

Mostly she calls late at night, since after eleven the rates go down by more than half. Just last night, she called past midnight about some trivial matter, going on and on till my right ear started to hurt, and I transferred the receiver to my left ear and back again. I certainly had not expected to hear from her first thing in the morning.

That the telephone rang the moment I plugged it in suggested that she had been on the edge of her seat, waiting impatiently to get through. This happens frequently, generally when she has some distressing tale to relate such as how her old clunker of a car was stolen from where she left it parked in the street for the night (only to mysteriously reappear in the same place a few days later), or how the plumbing she just had installed broke down, or how one of her two cats was taken sick. The problem is never anything that calling me will fix.

Nanae’s voice is low, with distinct variations: it can be brimming with resentment and malediction, distraught with loneliness, quavering with illness, straightforwardly cheerful, or, rarely, filled with exaltation. Fortunately, today’s ‘Hello. Hi there’ sounded fairly upbeat.

I felt my irritation give way to a rising tide of relaxation. ‘What’s going on? You’re calling early.’

‘You unplugged the phone again, didn’t you?’

‘Well, last night after we talked I was up late.’

‘Jesus, how can you study all the time like that?’

‘I don’t study. That’s the whole trouble.’

Despite my protests, Nanae never takes such claims seriously. Full of self-pity for being out on her own in Manhattan, she is unable to conceive how I, firmly embedded as I am in the university system with a proper identity as a graduate student, a scholarship to pay my living expenses, and university health insurance to boot, could have any problems whatsoever. If she so much as catches a cold, she will call me up and cough into the receiver: Do you know how lucky you are? I can’t even afford to go see a doctor. You have no idea what kind of money they charge for your first visit! —as if this is my fault. And naturally, she believes that she endures far greater loneliness than I do, when in fact she has several people whom she talks to on the telephone or eats lunch with and a place of work that she goes to, however irregularly, so her social life is considerably more normal than mine. She also has a pair of cats that she lavishes affection on. For a good year now I have rarely left the apartment, and I have hardly had a real conversation with anyone but her. Even so, she is convinced that she is more to be pitied than me. Strangest of all, I feel the same way.