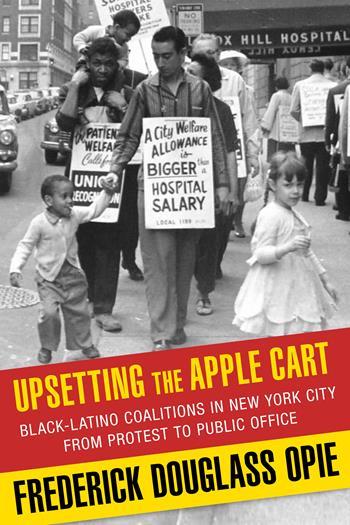

The Fate of Black and Latino Politicians in New York City — Frederick Douglass Opie

As suggested by the subtitle, in Upsetting the Apple Cart: Black-Latino Coalitions in New York City From Protest to Public Office, Frederick Douglass’s book tracks the rise of Black and Latino politicians, which in some ways reached its apex with the 1989 election of David Dinkins as the first African American mayor of the city. He was also the last New York City mayor of color.

In the conclusion to the book, Opie considers why gaining citywide or statewide offices has proven so difficult for Black and Latino politicians and what can be done:

There were a number of Black-Latino Progressive coalitions that waged battles before the creation of Latinos for Dinkins. David Dinkins’s campaign victory and his administration’s support for the political reapportionment and increase in the number of seats in the City Council from thirty-five to fifty-one have ensured that blacks and Latinos are today well represented among New York City elected officials. But representation in higher citywide or statewide offices still remains elusive, largely because of racial fragmentation within the Democratic Party.

A number of problems remain among black and Latino elected officials in Albany. They need to clearly articulate issues relevant to the communities they represent, but, most of all, their efforts and reputations have been seriously hampered by the rampant corruption in Albany. Officials have to do a better job investigating allegations of improprieties among elected officials. For example, just as the 2013 New York mayoral election began to rev up, corruption scandals and the arrest of black and Latino legislators from New York City rocked Albany. “You have a better chance” of being led out of the Assembly or the Senate in Albany in “handcuffs than you do being voted out of office,” says Ken Lovett, Albany bureau chief for the Daily News.

In order to regain the strength that had helped Dinkins into office, black and Latino elected officials need to mobilize around issues important to Progressives in the same way that labor leaders did in hospitals in the 1950s and 1960s, as student activists did on college campuses in the late 1960s, as activists did on the streets and in tenements in the 1960s through the 1980s, and as various groups did in 2012 (under the aegis of Occupy movements that first began in New York City).

The demands of black and Latino Progressive coalitions from 1959 to 1989 were consistent and remain important concerns today: a living wage in which to provide better housing, health care, food, and educational opportunities for them and their families; the end of police brutality; and greater black and Latino representation among elected officials. On the question of ending police brutality, Progressive coalitions have been engaged in a campaign for almost two decades to end the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk crime-prevention program. It is viewed as a civil rights violation, which police officers most often carry out against male youth in black and Latino communities across the city. In fact, stop-and-frisk remained a constant part of the debate among candidates vying for the Democratic nomination for mayor of New York.