Back to School with Anne Campbell — Mike Chasar

The following post is by Mike Chasar, author of Everyday Reading: Poetry and Popular Culture in Modern America. The essay was also published in Arcade:

A little less than a year back, I wrote about Edgar Guest, the longtime poet of the Detroit Free Press who published a poem in that paper seven days a week for thirty years. The national syndication of his verse made Guest a household name, got him dubbed the “people’s poet,” turned him into a popular speaker, and made him a very rich man even if it didn’t secure him a place in scholarly histories of American poetry. Indeed, after mentioning Guest as part of a Modernist Studies Association panel a few years back, I happened to run into a prominent poet-critic in the airport and, in making small talk about the panel while we waited for our flights, he confessed that until my talk he’d never even heard of Guest. By contrast, my mother-in-law owned several of Guest’s books before she moved out of the family house and into a retirement home; when I was helping her move and opened them, other poems by Guest that she’d clipped from newspapers and magazines and stored between the pages came fluttering out.

If the poet-critic I just mentioned had never heard of Guest, it’s probably safe to say that he’s never heard of Anne Campbell either—the poet whom the Detroit News hired in 1922 to better compete with the Free Press. Called “Eddie Guest’s Rival” by Time and “The Poet of the Home” by her publicity agents, Campbell would go on to write a poem a day six days a week for twenty-five years, producing over 7,500 poems whose international syndication reportedly earned her up to $10,000 per year (that’s about $140,000 adjusted for inflation, folks), becoming a popular speaker in her own right, and proving that neither the Free Press nor Guest could corner the market on popular poetry. Indeed, a 1947 event marking her silver anniversary at the News drew fifteen hundred fans including Detroit’s mayor and the president of Wayne State University.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Campbell lately. For starters, I’ve been working on an essay about women’s poetry and popular culture for the Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century American Women’s Poetry, and Campbell’s clearly a central part of that history. Then I had the excellent good fortune of meeting Campbell’s granddaughter, who’s been very helpful in sketching out some of the details of Campbell’s life for me. Anne was born in rural Michigan on June 19, 1888, possibly finished high school, married the Detroit News writer and future Detroit city historian George W. Stark when she was twenty-seven, had three children, performed and recorded regularly with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra doing readings during intermissions in the 1930s, read on local and national radio, was active with the March of Dimes, and with George was a fixture of Detroit’s cultural life and friends, of course, with Guest. She published her first poem (where else, right?) in the Free Press when she was ten, won a state prize for a Memorial Day story and poem when she was fourteen, was first paid for her poetry when she was seventeen, gave a popular talk called “Everyday Poetry” on the Lyceum circuit, and published at least five books of poetry, one co-written with George. (For a bunch of blurbs and publicity materials about her, check out the pamphlets here and here.) She died in 1984.

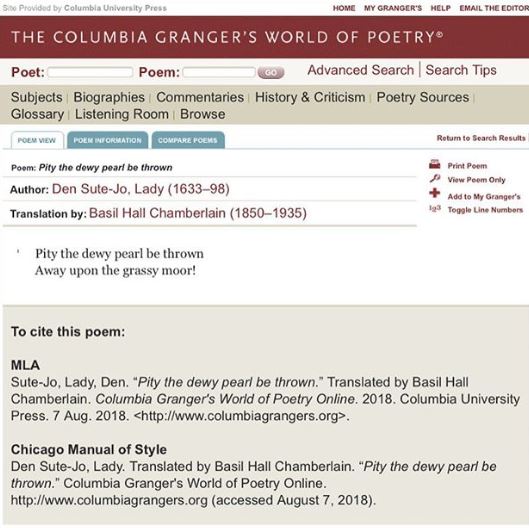

I’ve also been thinking about Campbell because it’s back-to-school season, and, along with a new Trapper Keeper, I just purchased the card pictured above, which features Campbell’s poem “Visitin’ the School” and is identified as “A Souvenir of Anne Campbell’s Visit to Your School, Compliments of The Detroit News.” (The back of the card is blank, by the way, but it has glue marks on its four corners, suggesting that someone saved it in his or her poetry scrapbook; in fact, I’ve seen poetry scrapbooks dedicated entirely to collecting Campbell’s poems.) Here’s “Visitin’ the School”:

Oh, dear, I feel like sich a fool

When folks come visitin’ the school.

I never git my problems well,

An’ jist can’t read an’ write and spell.

When teacher asts me to recite,

Although I try with all my might,

I feel the red burn in my cheek,

An’ my throat swells so I can’t speak.

My both knees shake an’ sweat rolls down.

An’ nen when I see teacher’s frown,

I git so scared, I wish fur fair

That I was any place but there.

When I git big an’ have a boy

I’ goin’ to make his life all joy.

No matter what the teacher’s rule,

I’ll not go visitin’ the school!

It’s an odd little poem, isn’t it? It’s kitschy in a way that Daniel Tiffany’s recent book My Silver Planet: A Secret History of Poetry and Kitsch can help us to understand, and although the second and third stanzas don’t disclose the exact content of the recitation, they nevertheless call most readily to my mind the history of poetry memorization and recitation that Catherine Robson takes up in Heart Beats: Everyday Life and the Memorized Poem; seen this way, “Visitin’ the School” is thus a poem about poetry.

But under the cover of innocence—the kitchiness, the schoolroom, the slightly baby-talk language, the rudimentary rhymes, etc.—I think Campbell’s poem’s got something more going on. Noteworthy for how it doesn’t assign a gender to teacher, student, or classroom visitor (thus making a role in the child’s predicament available to all students, teachers, and classroom visitors), “Visitin’ the School” is super concerned with the subject of reproduction: whether or not the child’s oral expression can be reproduced in print; whether or not the child can faithfully reproduce what “teacher asts me to recite”; how the child will “git big an’ have a boy”; and, ultimately, how the child vows to not reproduce the cultural practice of “visitin’ the school.”

Locating a voice of protest and dissent in the child—the weak, scared, young, and nearly voiceless (“my throat swells so I can’t speak”) subject put under pressure by multiple forms of surveillance—Campbell’s poem becomes unexpectedly politicized, questioning, rather than confirming, the legitimacy of normative educational practices. If we do not hear this protest, it’s not because it’s not there, but because we who teach and visit classrooms at all levels fail to afford its apparently rudimentary poetic expression—by someone who “jist can’t read an’ write and spell”—the seriousness it deserves. As school begins, and as many of us may feel moved to lament the poor writing skills our students bring with them, that’s a lesson worth keeping in mind.