Iris Barry, the Askew Salon, and The Museum of Modern Art

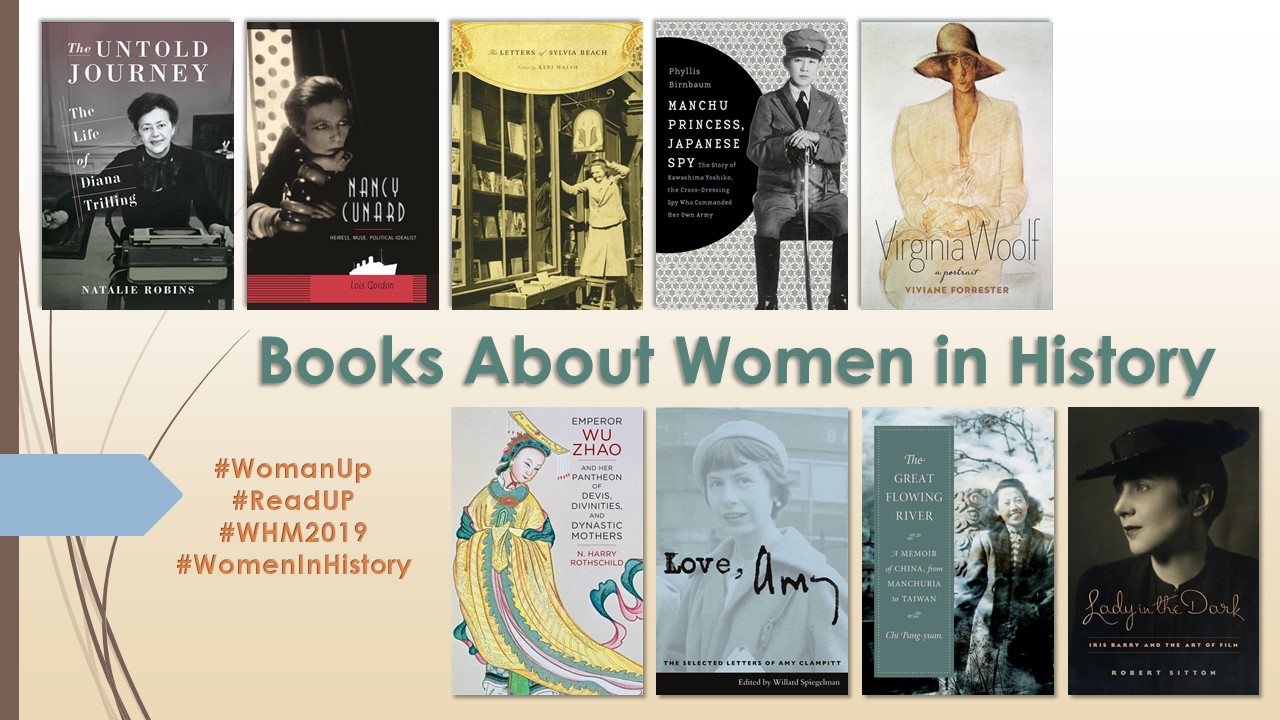

We conclude our week-long feature on Lady in the Dark: Iris Barry and the Art of Film with an excerpt from the book.

Iris Barry had made her mark in England as a film critic for The Spectator in the 1920s. She co-founded the innovative London Film Society in 1925 and in the next year published a book, Let’s Go to the Pictures, explaining why film is an art form. Nonetheless, she struggled in New York from her arrival in 1930 until she achieved some measure of stability as the first Curator of Film at the Museum of Modern Art in 1935. This reversal of fortune came through meetings at the Askew salon, where she was introduced to the young director of MoMA, Alfred H. Barr Jr.

Iris Barry’s connection with Museum of Modern Art Director Alfred Barr came through the Askews. Kirk Askew was a Harvard graduate who worked for the New York office of Durlacher Brothers, a major European art dealership. His wife Constance was much admired as a hostess and became Iris’ life-long friend. The Askew salon comprised a petrie dish of modernism, in which movers and doers in all the arts met to exchange ideas. In his Memoir of an Art Gallery, art dealer Julien Levy recalls that “the best and most culturally fertile salon I was to know in the thirties grew from little Sunday gatherings at Kirk and Constance Askew’s, where many of my Harvard and New York friends gathered. Kirk’s system of invisible manipulation kept the evening both sparkling and under control [and] combined the hidden rigidity of as carefully combed a guest list as any straight and proper social arbiter might arrange, with the frothy addition of the uninhibited of Upper Bohemia, plus, one at a time, to avoid jealousy and sulks, a single real lion. Two were asked together only if they expressed a desire to meet or already knew and liked each other and admired each other’s work. There developed and was maintained a colorful variety of conversations, many fruitful contacts, some light flirting, some sex, and a little matchmaking, with an occasional feud for spice. A small group of regulars came every week and provided the dependably witty core of the parties, so that on rainy or otherwise off nights there still would be no risk of boredom….”

Despite the fact that many members of the Askew salon were homosexual, the rules of conduct of the period discouraged overt activity. As Steven Watson, author of Strange Bedfellows, a study of the sexuality of modernist culture put it, “once a man made a pass at another man, the butler brought him his coat. The rule was, we do not camp in public.”

A second salon Iris sometimes attended, hosted by Muriel Draper, took on a more political tone and had rules of conduct more permissive than the Askews. Muriel Draper had entertained artists in a well-known London salon between 1911 and 1915, and since her return to New York carried on a successful interior design business among the well-to-do. Her leftist leanings later got her into trouble with the House Un-American Activities Committee. Despite her association with left-wing organizations in the 1930s, however, she was apparently not a Communist Party member. Esther Murphy, Paul and Jane Bowles and others in the Draper salon flirted with Communism, but political or, for that matter, sexual orientation made no difference at the Drapers. Virgil Thomson, a frequenter of both salons, referred to the group as “the Little People”, since many there, like Thomson himself, were of short stature. Of the two salons, even the Bowleses preferred the Askew’s. Paul Bowles’ biographer, Gena Dagel Caponi, noted that “despite living separately, Jane and Paul were very much a couple when they socialized. They regularly attended gatherings at the [Askews], who held what Paul called ‘the only regular salon in New York worthy of the name.’ There Paul played the piano and sang his own songs, while Jane visited, sitting first on one man’s lap and then in another’s. omposers Virgil Thomson, Aaron Copland, Elliot Carter, and Marc Blitzstein could be counted on to be there, as could Lincoln Kirstein and George Balanchine and their dancers. Several connected with the Museum of Modern Art attended….Poet E.E. Cummings and John Houseman were often there as well. As Europe headed towards war, artists immigrated to New York and to the Askew salon. Among them were surrealists – Marcel Duchamp, Yves Tanguy, and Salvador Dali — who dominated the intellectual tone of the Askew salon from 1940 on; Paul felt at home with them, but Jane did not.”

At the Askews Iris sized up Alfred Barr as “a kindred soul…a youngish Wellesley College art professor who was a simple, direct Harvard aesthete whose wanderings about the museums of Europe and the salons of Paris had led him to envision the Museum of Modern Art. If he was a visionary, he was so in the best sense of being an intensely practical one.” Possessed of influential friends, Barr “could think on his feet with the best of them and was, to boot, an elegant parlor orator, attributes which beautifully accompanied his deep and abiding sincerity.”

Iris found that she and Barr “entertained a similar outlook on the motion picture as falling within the Museum’s proper scope of activity.” She promoted herself to Barr as the one to head a film component of the Museum. “No time was lost in pointing out to him that the only noteworthy attempt to make the motion picture known as a living art rather than ephemeral entertainment had come from the Film Society in London,” which had been handicapped “by the lack of any central repository from which important films of the past could be booked at will. The inference was plain; the Museum, by its avowed purpose and very nature as an institution for the study of contemporary art, should logically become that central repository.

“With this thesis Barr had no fault to find, but he regretfully elaborated his predicament: the financial set-up was simply insufficient to adequately support even the painting, sculpture and architectural departments of the Museum, much less found new ones at the present time. Indeed, the miracle was they had actually been able to get as far as they had, nor would they have in all likelihood had not the majority of sponsors made their grants prior to the great market crash. For example, at that very moment a librarian was desperately needed, yet there were no funds for the salary.” Iris jumped at the job. Adjusting her new hat, “a fetching trifle from Hattie Carnegie’s,” she told Barr she had been a librarian at London’s School of Oriental Studies, working with Arthur Waley, and would gladly take the job without pay. This provided her with “a toe inside the door” of the Museum. Among the chores she was charged with was the publication of the Museum’s monthly bulletin, in which she “inaugurated a policy of including thumbnail reviews of current films….”

Iris became a favorite of the Askews. She wrote [her friend] Sidney Bernstein that she had “been in and out of their house like an iceman these many moons” and esteemed them as “the sort of people who make America worth living in.” It isn’t clear exactly how Iris made her way into the Askew salon. One scenario has it that she carried a letter of introduction from the Laughtons. Museum of Modern Art historian Russell Lynes, who credits the Laughtons with stirring Iris into the “artistic compote” of the Askew salon, says that Iris met Philip Johnson “at a cocktail party at Joseph Brewer’s” and that Johnson, impressed with Iris’ “wit, agility and knowledge…told her she simply had to work at the Museum, that he would pay her salary and she would be the Librarian.”

Reflecting on these events some years later, Johnson recalled that he “first met Iris Barry at one of the salons at the Askews [or possibly Joseph Brewer’s] in 1930. We at once felt a friendship. I realized that she was hungry, so I gave her some food and bought her a dress. We went to Saks and bought one of the most unattractive dresses imaginable, but she had nothing to wear. She said she was in films and needed a job, any job. I asked Alfred Barr if there were any jobs at the Museum. He said, ‘No, but we are trying to found a library’. So she was made the librarian. She knew nothing about libraries, so she was sent to library school at Columbia, which she hated. I paid her living for a while. She sat in the penthouse of the house at 11 West 53rd Street. I gave my library of architecture books.” It would be some time, however, before a film library would emerge from the book library of the Museum of Modern Art….

Although a small salary as Librarian began to replace the subsidy from Philip Johnson, Iris still scraped along at MoMA. While attending Columbia University “twice a week to study library work,” she wrote Sidney Bernstein, an effort she described as “a vast bore but a bit of politics toward getting more salary,” she labored in the penthouse at 11 West 53rd street that was the first permanent home of the Museum. Between 1929 and 1931 the Museum had been housed in the Heckscher Building on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th street. To escape the confining spaces of the single floor of the building it occupied, the Museum was moved to a brownstone abutting the back of the Rockefeller family home on West 54th street, a building also owned by the Rockefellers. The family leased the building to the Museum’s trustees for a fraction of the cost of renting the Heckscher Building. This 11 West 53rd street address persisted after the original brownstone was razed to make way for the new Museum building in 1939.

Iris decided she needed to live near the Museum. Her decision proved fateful. She took an apartment underneath one occupied by a Wall Street broker named John Abbott. Also known as Dick, Abbott was a tall, handsome man fourteen years her junior, and from an established Delaware family. His neat appearance, slicked-back hair and rimless glasses gave him an air of respectability, and when he confessed to Iris that he preferred art and films to stocks, the statement undoubtedly piqued her interest. She was, after all, on her own if still married. The first thing she did with Dick Abbott was to borrow a painting from his apartment. “It really looks what they call ‘darling,’” she wrote Bernstein of her new apartment, “especially as there’s a ‘real’ painting by Eugene Berman over the sitting room fireplace which comes from upstairs but looks better in my room, lends tone no end.” Iris may have decided at this time that Abbott might lend the kind of “tone” that fit in with the Museum. The two began to date, attending films and art openings until they became associated as a couple in social circles. Iris even took Abbott to the Askews, and he apparently went over well enough, although no one seems to have remembered him. No one could have known that in 1939 Abbott would begin to take control of the Museum away from Alfred Barr.

During the Spring of 1934, again through contacts made at the Askews, Iris attended the premier of Virgil Thomson’s innovative operetta, Four Saints in Three Acts, at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. Thomson’s work was presented by his Askew salon associate, A. Everett “Chick” Austin, director of the Atheneum. The opera, with its all-black cast, scenario by Gertrude Stein, cellophane sets by the Stettheimers, choreography by Frederick Ashton, and music by Virgil Thomson was only one of many innovations emergent from the Askew salon. John Houseman would become influential in the Federal Theater Project, with its Living Newspapers, Voodoo Macbeth production in Harlem in 1936 and the Marc Blitzstein musical, The Cradle Will Rock, now revived on Broadway. Lincoln Kirstein not only brought George Balanchine to America, he was instrumental in introducing vernacular dance to our stages and screens. The New York City Ballet was his inspiration. The legacy of Philip Johnson stands on many New York City streets, from the AT&T Building to the Mies Van der Rohe Seagram Building, which Johnson championed and in which he had his offices. Johnson identified Chick Austin’s house in Hartford, a Palladian-style stage-set 86-feet wide and 18-feet deep with two false windows, as the “first post-Modern house.” And what would a modern art museum look like without the example set by Austin in Hartford and Barr in New York City? Then there was Iris, and the introduction of films into museum programming. The wonder is that these, and many others identified with Modernism, met and exchanged ideas at the same place.