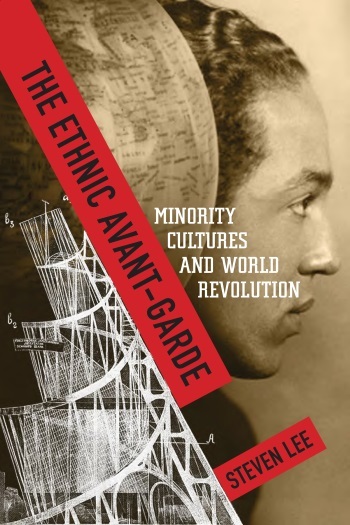

An Interview with Steven S. Lee, author of "The Ethnic Avant-Garde"

“Up until Black Lives Matter, there was a lot of talk about ‘post-race’ and ‘post-identity,’ which now seems awfully naïve. I think my book helps us to grasp the ongoing salience of racial and ethnic divides, namely, by explaining how these divides were reinforced after the interwar years.”—Steven S. Lee

The following is an interview with Steven S. Lee, author of The Ethnic Avant-Garde: Minority Cultures and World Revolution:

Q: What do you mean by “the ethnic avant-garde”?

Steven S. Lee: Two things. First, it’s a historical grouping comprised of minority writers and artists from around the world who, particularly in the 1920s and 30s, drew inspiration from the Soviet Union. They saw interwar Moscow as a beacon of both world revolution and cultural experimentation—Moscow as a center for both the Communist International (Comintern) and the international avant-garde. Rather than shared phenotype or descent, what bound this group were the forms in which it trafficked, namely, the defining techniques of the Soviet avant-garde—montage, fragment, interruption. For instance, the ethnic avant-garde encompasses Langston Hughes’s translations of Vladimir Mayakovsky; abstract suprematist shapes depicting the Bolshevik Revolution as Jewish messianic arrest; and a Soviet futurist play about China that became Broadway’s first major production with a predominantly Asian American cast.

But I also present the ethnic avant-garde as a utopian aspiration, one that exceeds the interwar years and the Soviet Union and that persists into the present. It’s the dream of advancing simultaneously ethnic particularism, political radicalism, and ar¬tistic experimentation—a dream largely crushed by Stalinism and the Cold War, but which I trace forward to Red China, 1960s activism, and contemporary American writing. As a result, we get to see the global scope and experimental potential of minority cultures, debunking the notion that particularism yields provincialism.

Q: How did you arrive at this grouping?

SSL: It’s been a roundabout journey. The project began in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, where I spent a year comparing Soviet Korean and Korean American literature. In 1937, Stalin deported approximately 180,000 Koreans from the Russian Far East to Central Asia, suspecting that they might serve as Japanese spies. And yet this wasn’t only a tragedy. The strides that Soviet Koreans made and continue to make, particularly in the cultural and political spheres, are just astounding. For instance, the Soviet Union’s greatest cult rock star, Viktor Tsoi, was half-Korean.

While working on this project in Tashkent, a friend told me about Langston Hughes’s 1932 visit to Uzbekistan and about his little-known, Moscow-published book that favorably compared the Soviet “East” to the American South. From there, the project began to grow broader in scope—from Soviet Koreans to Soviet “national minorities” as a whole, and to the contrasts between American multiculturalism and its Soviet counterparts. I became particularly interested in the long, troubled history of American minorities who saw the USSR as a “frontier of hope” (to quote the Jewish American philosopher Horace Kallen).

Of course, many of the figures I follow eventually became disillusioned with Soviet policies; some of them perished during the Stalinist terrors. However, in trying to understand the allure of what Claude McKay called the “magic pilgrimage” to the USSR, it’s important to keep in mind that these writers and artists weren’t just interested in official policies. They were also drawn to the creative possibilities opened by the likes of Sergei Eisenstein and Vladimir Mayakovsky—this lionized branch of the international avant-garde which, as Slavists well know, had itself long been fascinated by minority and non-Western cultures.

Q: How does the ethnic avant-garde change our understanding of the historical avant-garde of the interwar years?

SSL: One of my aims has been to highlight the interwar avant-garde’s inclusive, decolonizing potential, and the key has been to think about avant-gardism as the estrangement of time and history. Following the lead of Walter Benjamin and Peter Osborne, as well as Slavists like Masha Salazkina and Jane Sharp, the book uses “ethnicity” (with its connotations of the past and descent) to highlight the avant-garde’s ability to interrupt linear progress.

Allow me to elaborate. Typically, we see the avant-garde as future-oriented—the revolutionary vanguard and artistic avant-garde as agents of progress—but of course, there are plenty of instances of cutting-edge artists and writers looking to the past for inspiration. Picasso’s incorporation of African masks, Pound’s interest in Confucianism, and Eisenstein’s Mexican film project are well-known examples. The book adds several more to the mix: for instance, we see the futurist Mayakovsky attempting poetry in an “Afro-Cuban” voice, praising Diego Rivera for painting the “world’s first Communist mural,” and then relaxing at a leftist Jewish summer camp on the Hudson.

What I argue is that Mayakovsky and his fellow Soviet avant-gardists embraced (and often identified with) minority peoples and cultures in order to rethink linear progress, and in the context of the Comintern such efforts had a uniquely radical, decolonizing function. This is because the Soviet avant-garde’s efforts to estrange history complemented the Comintern’s efforts to do the same—to coordinate a world revolution that would include peoples of all backgrounds and all stages of historical development.

Q: You mentioned that the ethnic avant-garde persists into the present. What contributions does it make to contemporary discussions surrounding race and ethnicity?

SSL: Up until Black Lives Matter, there was a lot of talk about “post-race” and “post-identity,” which now seems awfully naïve. I think my book helps us to grasp the ongoing salience of racial and ethnic divides, namely, by explaining how these divides were reinforced after the interwar years. In the 1920s and 30s, the dream of world revolution attracted peoples of all backgrounds, which allowed for the cross-cultural encounters and coalitions that I explore. But then in the face of Stalinism and the Cold War, many people turned inward. Over the course of the book, we see instances of minority cultures—African American, Asian American, Jewish American—advancing first socialist internationalism, and then, after World War II, liberal pluralism.

Of course, much good came from this turn, namely, the hard-won advancement of civil rights, a more inclusive literary canon, and a potent language for combating prejudice. But a lot was lost as well. The boundaries separating different races and ethnicities became far more entrenched. In addition, it became increasingly difficult to think about race and ethnicity in relation to class inequality and global capitalism. My sense is that this lost horizon lies at the heart of Black Lives Matter. We’re hitting against the limits of liberal multiculturalism, and the book tries to mine the past for more radical configurations of identity.

Q: The book concludes with a discussion of the 1991 Soviet collapse and the notion that this pointed to “the end of history,” that is, the lack of any alternative to liberal democratic capitalism. What does it mean to, in your words, advance “beyond ‘the end of history’ by resisting nostalgia and cynicism alike”?

I’m not at all interested in resurrecting twentieth-century communism. One of the challenges of writing the book was to capture the ethnic avant-garde’s allure while simultaneously emphasizing Stalinism’s often violent, near-destruction of it. In short, the book confronts both the promise and failure of world revolution—both its “horror” and “glory” as Richard Wright put it in his 1944 disavowal of communism.

But the fact that this tragic history cuts across racial, ethnic, and national lines gives me hope. I focus on the United States and the Soviet Union, but similar exchanges played out all around the world. Going forward, it would be wonderful to bring these histories into dialogue with one another. And so at the end of the day, the book points not to repeated revolutions, but to new scholarly and creative communities, bound by shared encounters with the vanguards and avant-gardes of the last century. I think from there, it becomes possible to imagine new ways of estranging the present.

3 Responses

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thank you so much for this blog.

Good to read