Santiago Zabala on Signs from the Future

Spending a day without being warned about the dangers of climate change, artificial intelligence, or financial crisis is challenging. We are constantly warned but seldom listen—that is, interpret and take action. But why? Santiago Zabala’s new book, Signs from the Future. A Philosophy of Warnings, attempts to answer this question by thinking of philosophy as a warning rather than a system or method. He argues that warnings—unlike predictions—invite us to see the possibility of a radical break from the present. While predictions tell us to submit to the inevitable, warnings ask us to take part in an alternative, in shaping a different future. Zabala’s book interprets renowned philosophers’ warnings on God, science, gender, and evil, illustrates through popular culture how we ignore them, and envisions a politics of warnings to help us confront hidden emergencies through collective listening, interpretation, and action.

Q: What is the central idea behind Signs from the Future, and why do we need a philosophy of warnings today?

Santiago Zabala: This book aims to think of philosophy as a warning, and its goal is to outline a “philosophy of warnings.” Although no one has ever written a formal philosophy of warnings, many philosophers have warned us about God, science, and many other concepts. But unlike the philosophy of religion or the philosophy of science—which have become distinct subdisciplines—my philosophy of warnings does not pretend to expertise in the applications of the field. Also, unlike recent philosophies of animals, plants, or insects, this philosophy is more than a philosophical elucidation of a global environmental emergency; it is the ontology within which these issues and philosophies exist. Like animals, plants, and insects, warnings have been a topic of philosophical investigation for centuries. The difference lies in the meaning they have acquired now. The problem is that too often, warnings are dismissed—much like the artists, scientists, environmentalists, and intellectuals who deliver them. Why don’t we listen?

Q: Why don’t we listen to them? What holds us back?

Zabala: Primarily the ongoing “global return to order through realism.” This return is not only political, as demonstrated by the various right-wing populist forces that have taken office worldwide, but also cultural, as shown by the return of some intellectuals to Eurocentric Cartesian realism. The idea that we can still claim access to truth without being dependent upon interpretation presupposes that knowledge of objective facts is enough to guide our lives or listen to warnings. Within this realism, warnings are cast off as unfounded, contingent, and subjective, even though philosophers and historians of science such as Bruno Latour and Naomi Oreskes continue to remind us that “no attested knowledge can stand on its own” because only “the social character of scientific knowledge makes it trustworthy.”

Q: Isn’t the suspicion of warnings also a consequence of antiestablishment voters rejecting authority?

Zabala: Yes, they reject authority because it often seems sanctioned only by institutional powers. But this prejudice—as Hans-Georg Gadamer pointed out—does not take into consideration the difference between “authoritative” and “authoritarian”: the latter has not earned its authority and is concerned primarily with power, order, and obedience; the former instead earns its authority through a foundational consensus and receives not so much obedience as trust. The distinction between warnings and predictions is also founded on this difference.

Q: So what is the difference between warnings and predictions?

Zabala: Warnings, unlike predictions, are weak, vague, and subtle statements in the form of announcements that are often ignored. This is why they can be understood only through interpretation, an involvement that concerns our existence, rather than an objective representation in the mind. Referring to them as signs from the future is a way of recalling such weakness, in other words, their call for interpretation. While predictions belong to futurology—where the future is forecasted from the present trends in society—warnings are hermeneutical; they strive to change the future by reinterpreting the past.

Q: Which warnings can we trust?

Zabala: To respond to this question, it is first necessary to understand that truth is not the condition that determines whether we should listen to warnings. Whether a warning comes to pass is secondary to the intensity and pressure it exercises against hidden emergencies because it depends on our willingness to listen and interpret. Although most warnings we are used to come from scientists, they work better when they come from activists, artists, or journalists, as I explain in the book. Jonathan Glazer, for example, described his 2023 movie The Zone of Interest—loosely based on Martin Amis’s novel about the life of commandant Rudolf Höss and his family next to Auschwitz—“not a document. It’s not a history lesson. It’s a warning.” Glazer’s warning—regarding the danger of repeating another genocide—through a movie does not have less validity than that of the Holocaust historian Timothy Snyder, who begins Black Earth by making a similar point: the “Holocaust is not only history, but warning.” The difference between the two warnings is not one of kind but rather of degree, intensity, and depth. The truth of this genocide is not debatable—just like the scientific evidence of climate change or Julian Assange’s revelations—but whether we listen and interpret its signs, messages, and meaning is.

Q: In the book’s first part, you interpret Simone de Beauvoir’s famous sentence, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” as a warning. Why is this a warning?

Zabala: Unlike predictions, which would claim to know a person’s gender because they presuppose a rigid definition linking gender to inherited facts, warnings are announcements meant to preserve us from the threat implied by categories of knowledge, rationality, and realism. For Beauvoir this threat is the reduction of women to “what she has been, to what she is today,” in other words, to “the Other.” Her warning was meant not only to protect the identity of women from having a fixed destiny but, most of all, to understand femininity as a reaction to a situation rather than the consequence of biological facts. Although “these facts cannot be denied,” she wrote, “in themselves they have no significance” because becoming a woman is a matter of embodying a specific set of habits, behaviors, and choices that can only be explained existentially. Her goal, like that of other thinkers such as Judith Butler and Paul Preciado—whose contribution I discuss in the book’s second part—is not to tell people how to live their gender but rather to allow them to find their way in a world that often judges their identity in an inappropriate, cruel, and narrow way.

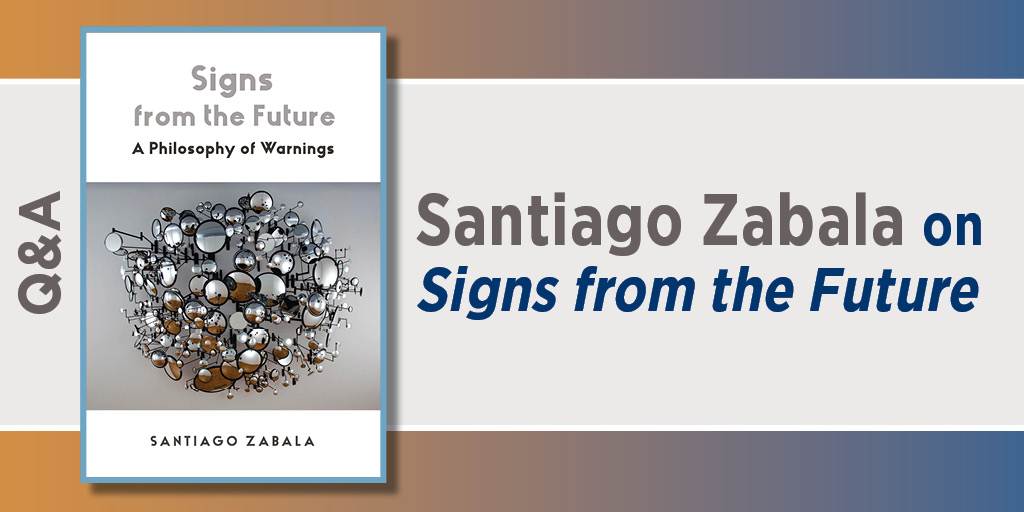

Q: Is the cover image supposed to illustrate what warnings are and what constitutes them?

Zabala: Yes, as one walks toward Graham Caldwell’s sculpture, the horizon of what one sees through the mirrors widens, giving a feeling of intensity and pressure that calls for a response. These mirrors, like the rear-view mirrors on cars, are not only different sizes but also positioned in such a way as to force us to select which one to look at, that is, to change the future.

Categories:Philosophy

Tags:philosophy of warningsSantiago ZabalaSigns from the Future