Stepping Ashore the Fennoscandian Shield in the Åland Archipelago

Markes E. Johnson

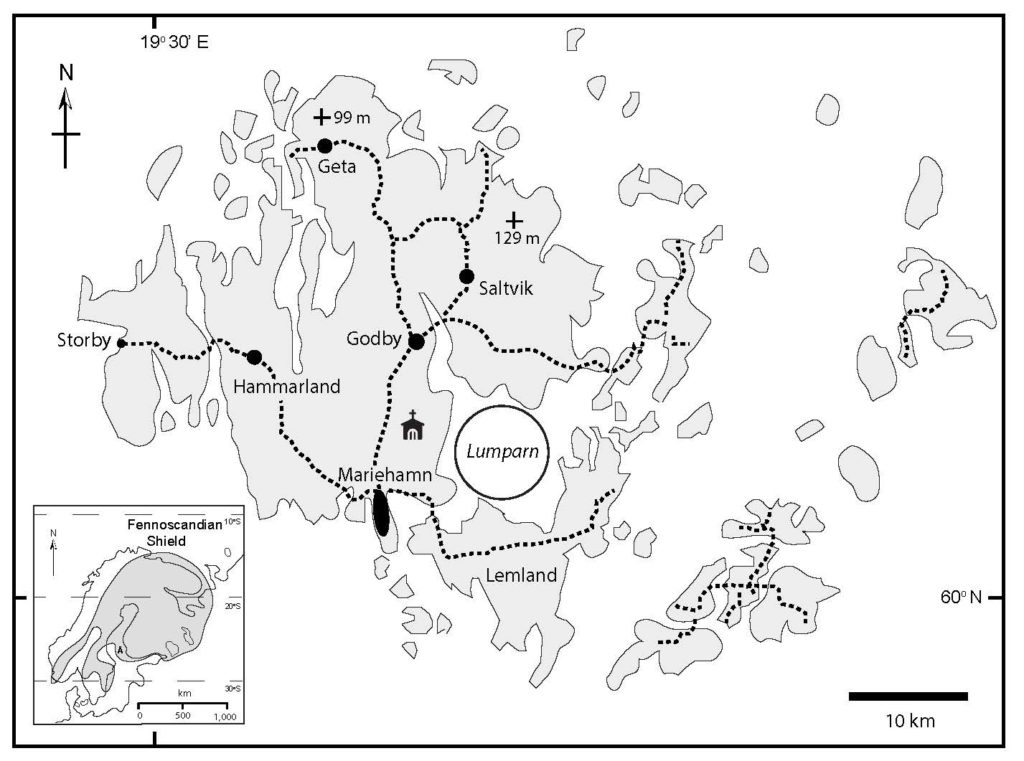

In the narrow Gulf of Bothnia between Finland and Sweden, the Åland Islands are dominated by exposures of the 1.6-billion-year-old Rapakivi granite. Limestone is scarce and its fossil content largely unknown to the outside world. Sixty islands are inhabited, surrounded by thousands of barren islets and rock skerries having a composite area of 600 square miles (1,554 km2). The largest island is Fasta Åland, with the principal town of Mariehamn (population 11,757). Orrdalsklint is the highest point, with an elevation of 423.5 ft (129 m) above sea level. It is a bucolic landscape with small hamlets scattered over a gentle, patchwork terrain of meadows, apple orchards, and evergreen forests interspersed by lakes. Bare granite dominates the convoluted shores of the main island and its related islets. For the geologist, the archipelago presents a friendly and accommodating landing place on the greater Fennoscandian Shield that crowns much of Finland and Sweden. Like the great Canadian Shield, it occurs at the core of a major continent. Fasta Åland offers additional appeal on account of an ancient crater flooded by seawater in a central basin called Lumparn. The technical term is an astrobleme, and the Lumparn crater (6 miles or 10 km in diameter) is an erosional remnant left by the impact of an extraterrestrial object. Sunken limestone deposits dating to around 450 million years ago from the Ordovician period are lodged within and were preserved from erasure by the advance of continental glaciers during the last 800,000 years.

Dolostone (limestone rich in magnesium) strata described in Islands in Deep Time (chapter 3) are on the Jens Munk Archipelago at Churchill on Hudson Bay, and there they represent a slightly younger package of Ordovician rocks on the edge of the Canadian Shield.[i] My partner, Gudveig Baarli, and I worked the Churchill shores and also contributed to studies on limestone strata of comparable age in the Oslo district of Norway off the Fennoscandian Shield.[ii] During that time, Scandinavia was subject to major storms not unlike those signaled by coeval strata at Churchill. Today, Canada’s Churchill in northern Manitoba, Norway’s Oslo region, and Finland’s Åland align close to a latitude around 60° north from the equator. Some 450 million years ago, all were located south of the Ordovician paleoequator in a more temperate climate devoid of winter snow and ice. To visit Churchill, Oslo, or Åland is for the geologist a passage into deep time, where it is possible to set foot on the shores of truly ancient continents brushed by warm seas.

Our July 2023 excursion was by air from Stockholm to Mariehamn, a short hop of barely half an hour. The archipelago is a curious outlier of Finland, where the 30,000 inhabitants speak Swedish and enjoy home rule within a demilitarized zone. Their capital dates to 1861, during a period of Russian influence when the city was named after Maria Alexandrovna, the spouse of Tsar Alexander II. The region flies its own flag, which mimics the national flag of Sweden with its yellow cross on a field of blue—but with a red cross superimposed. Published literature on Ordovician geology is hard to come by, and the single English-language source available prior to our visit was by an American paleontologist who described microfossils called conodonts, extracted mainly from limestone underwater along the northern rim of Lumparn.[iii] The same source from 1980 proposed that the basin was formed by the impact of a meteorite or comet but offered little direct evidence beyond its circular shape. Moreover, the author suggested that the Kalkskär limestone in Lumparn was largely devoid of body fossils due to deposition in brackish water. On visiting the Åland Museum in Mariehamn at the outset of our visit, we were astonished to find an exhibit with a huge diversity of marine invertebrates from the local limestone. The fossils were collected by a local rock hound named Keijo Hiltunen, and one of the museum curators told us how to find him. It had been my ambition to see the Kalkskär for myself, even if it meant I had to take a swim in the brisk summer waters of the Lumparn. Clearly, we needed to see this person and get his advice on where exactly to go for the best access around the crater shores.

Our next surprise occurred on our foray out of Mariehamn toward Godby, where we had arranged for a few days’ accommodation. The highway passed Saint Olav Church in Jomala, and we stopped to see the medieval building, parts of which date from the thirteenth century. The building stone used for the main edifice is the red Rapakivi granite, but the front portal to the church was constructed from local limestone. A more substantial source of limestone had once existed for use as building stone. A church brochure stated that no other church in Åland (or anywhere else in Finland) featured limestone construction or other limestone artifacts.

It was not difficult to find Mr. Hiltunen, who is a local celebrity and whose efforts as a rock hound had been honored by the issue of postage stamps bearing the likeness of his most treasured fossil discoveries. Among other sovereign rights, Åland issues its own postage stamps independently from the rest of Finland. We found him to be a gregarious individual only too happy to share a wealth of information with visitors stopping at his home on short notice. On entrance to the well-equipped workshop in a separate building next to his home, we were again astonished to find the place overflowing with limestone samples being prepared for extraction of well-preserved trilobites, various mollusks, and an extraordinary array of crinoids (sea lilies). All came from Åland, and the abundance and diversity of material showed that normal marine salinity had been in effect during intervals of the later Ordovician period. His unique discoveries from the Lumparn featured meteorite fragments of various sizes embedded in limestone, as well as limestone that had been brecciated on impact and infused with matter far more dense than ordinary limestone. In brief, Mr. Hiltunen possessed the golden fleece of the Åland archipelago, and we were privileged to bear witness.

The same day, we were conducted on a field trip to visit some of the spots where Mr. Hiltunen works his magic as a skilled amateur paleontologist. Descending the steep granite shore on the west side of the Lumparn, we were brought to a spot where slabs of limestone are visible in shallow water directly offshore. Winter storms break some of the limestone loose, and it washes ashore. Gudveig bent down and picked up a small coral (Favosites) characteristic of Ordovician strata elsewhere in Scandinavia and North America. Finally we were taken to a site near Saint Olav Church where a farmer had piled loose blocks of granite and limestone cleared from his fields after upheaval during the spring thaw. Mr. Hiltunen knew what kind of limestone to hunt and in short order pounded out a fossil brachiopod (Porambonites), which he handed to me as a souvenir. We had come to Åland not to take its fossils but to experience the atmosphere of a granite seascape inundated long ago by ephemeral contact with an Ordovician sea that left barely a surviving trace. It was a meteor, not a comet, that struck a spot where a cover of limestone was already in place; it left a crater where additional limestone would be deposited and embed bits of the fragmented meteor as well as an extraordinary array of marine invertebrates and even rare fish. The limestone is not exclusive to the Lumparn basin but also occurs beneath the plain on which Saint Olav Church resides at a slightly higher elevation outside the crater. During the remainder of our visit, we hiked some of the trails in the modest highlands in the northern part of Fasta Åland, which gave a sense of the granite landscape and its modern seashore with a sparse intertidal biota dominated by seaweed. Indeed, the Gulf of Bothnia is noted for its low salinity (only 5 to 7 parts per thousand in the south, whereas normal marine salinity is 35 parts per thousand). We left with the surety that fully marine waters washed this place during the late Ordovician period, but only barely and likely never advanced farther inland over the greater Fennoscandian Shield.

Markes E. Johnson is the Charles L. MacMillan Professor of Natural Science Emeritus at Williams College and the author of Islands in Deep Time: Ancient Landscapes Lost and Found.