Why Only Art Can Save Us, Part I

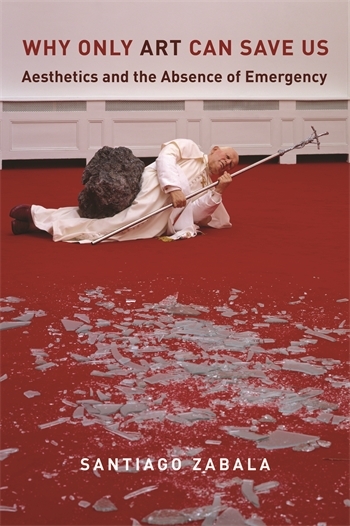

The following is part I of an interview with Santiago Zabala, author of Why Only Art Can Save Us: Aesthetics and the Absence of Emergency. Part II of the interview will appear tomorrow.

Question: Is this book for the philosophical community or the art world?

Santiago Zabala: It’s for both. I’m more interested to know what the art world will have to say about it as I can predict the philosophical community’s reactions to theories such as the one I explore here. A philosopher who posits that only those who thrust us into the “absence of emergency” are intellectually free today risks being marginalized as a radical who is surpassing the limits of rationality or common sense. But the problem is precisely this common sense. To be intellectually free today means disclosing the emergency at the core of the current absence of emergency, thrusting us into knowledge of those political, technological, and cultural impositions that frame our lives. I think the art world (from artists to curators and art historians) is better prepared for challenges, change, and even emergencies.

Q: How does this new book relate to your previous books?

SZ: Why Only Art can Save Us, like Hermeneutic Communism (coauthored with Gianni Vattimo), further develops my ontology of remnants, which I first illustrated in The Remains of Being. While in Hermeneutic Communism we tried to respond to what remains of Being through politics, here I attempt to respond to what remains through art, that is, how existence discloses itself in works of art. As with other post-metaphysical questions there is no straightforward response here, but simply an indication or sign from the future that we are compelled to interpret. In this book I’m interested in not only the signs but also the obligation this question implies, that is, the existential responsibility. This is why I agree with Slavoj Žižek when he calls for “a refined search for ‘signs coming from the future,’ for indications of this new radical questioning of the system … the least we can do is to look for traces of the new communist collective in already existing social or even artistic movements.” Recently, Vattimo and I explained why hermeneutic communism is still the most viable way to confront political emergencies such as the refuges crisis, ISIS attacks, or Trump’s presidency. Now the point is to tackle other emergencies that politics does not reach.

Q: You say that politics does not reach these emergencies because “the absence of emergency… has become the greatest emergency.” Can you explain the difference between “emergencies” and “essential emergencies”?

SZ: In order to explain this difference, it is first necessary to distinguish Heidegger’s “absence of emergency” (“Notlosigkeit”) from the popular “state of emergency” (“Ausnahmezustand”) of Walter Benjamin, Carl Schmidt, and Giorgio Agamben. The latter is a consequence of the former. Heidegger’s emergency does not refer to the “sovereign who decides on the exceptional case,” but rather to “Being’s abandonment,” which also includes the decision of a ruler to announce an emergency. If a political leader can decide upon a state of exception or emergency when Being has been abandoned, then the epoch’s metaphysical condition is its greatest emergency, and this condition explains the rise of the term “emergency” in the work of Bonnie Honig, Elaine Scarry, Janet Roitman, and many others. When Heidegger, in various texts of the 1940s pointed out how “lack of a sense of emergency is greatest where self-certainty has become unsurpassable, where everything is held to be calculable, and especially where it has been decided, with no previous questioning, who we are and what we are supposed to do,” he was concerned with this metaphysical condition. For example, we now live in a world where we are constantly under surveillance, and even the future is becoming predictable through online data mining. The problem has become not the emergencies we confront but rather the ones we are missing. These are the essential emergencies.

Q: Is the Trump presidency an emergency or an essential emergency?

SZ: He is an essential emergency. The fact that we did not predict he could win the presidency does not constitute an emergency per se; we all knew that whoever won the election would pursue or intensify the previous administration’s policies. Unfortunately, Trump is intensifying them and concealing even more the essential emergencies of climate change, civil rights, human rights, and others, which are now hidden behind his new appeal to order. He seems to be the incarnation of the absence of emergencies, determined to deny the most obvious emergencies by creating a condition that defines an emergency as anyone’s saying he is wrong. If the greatest emergency has become the lack of a sense of emergency, then art’s alterations of imposed reality, the new interpretations it can demand, disclose this emergency and demand a different aesthetics. The goal of this book is to outline this aesthetics of emergency or an ontology that posits art as fundamental to saving humanity from annihilation.

Q: And how can art save us from this?

SZ: Even though a work of art, such as a song or a photograph, is not that different from other objects in the world, it often works better than commercial media or historical reconstructions as a way to express emergency. The difference is one of degree, intensity, and depth. Media photographs can be truthful, but they are rarely as powerful as a photographic work of art. The series Soldiers Stories from Iraq and Afghanistan by Jennifer Karady or the Rwanda Project of Alfredo Jaar are paradigmatic examples here. Genuine art has the ability to disclose this emergency and help us grapple with it practically and theoretically. This is why Heidegger believes there is a fundamental difference between “those who rescue us from emergency” and the “rescuers into emergency.” The former are a means for “cultural politics,” that is, a way to conceal the emergency of Being; the latter are events that thrust us into this emergency. This distinction between artists and creators does not define who is more original but rather what is more essential: the emergency or its absence? If many artists have lost touch with the absence of emergency it’s not only because they are framed within cultural politics but also because as professional artists they have become the means of such culture. This is probably why Heidegger emphasized how the “growing ‘affability’ of the ‘profession of art’ . . . coincides with the secure rhythm that originates from within the predominance of technicity and shapes everything that is instable and organizable.” While some may consider this aesthetic theory a simple contribution to the discipline, its primary aim is ontological, that is, to specify how Being and existence are no longer givens but are rather the points of departure to overcome oblivion or annihilation. In sum, art should not simply be treated as an aesthetic object, but rather as an existential event that can save us from the essential emergencies.

Q: Is this why you call for the overcoming of aesthetics?

SZ: Yes, but this does not mean aesthetics must disappear. Rather, it has to surpass those metaphysical frames that conceal the absence of emergency. Against the ahistorical mode of aesthetics, which represents, orders, and manipulates beings and leaves us without a sense of emergency, emergency aesthetics dwells in this emergency. Contemplations of indifferent beauty, which rest on the correspondence between propositions and facts, are overcome in favor of interpretation and interventions that retrieve what is ignored by this traditional reflection. The emergency aesthetics I present does not simply overcome measurable representations and indifferent beauty but most of all creates the conditions to respond to the existential call of art in the twenty-first century. Only art can save us because, as Hölderlin pointed out “where danger is, also grows the saving power.”

Q: How is the book structured?

SZ: The book is divided into three chapters, each of which responds to the others. So while the last chapter, “Emergency Aesthetics,” outlines how to answer the ontological call of art in the twenty-fist century through hermeneutics, the second chapter responds to the “Emergency of Aesthetics” that I begin with. This emergency consists in the “indifference” that characterizes beauty as well as its “measurable” contemplation. Given that each chapter responds to the others, the reader is invited to read the book forward or backward as long as the works of art considered are interpreted as representing the possibility of salvation from metaphysics, that is, as revealing an aesthetics of emergency.

Q: Chapter 2 is divided into four sections that analyze contemporary social, urban, environmental, and historical emergencies through twelve works of art. Did the works of art suggest the emergencies or the other way around?

SZ: The artworks suggested or, better, “thrust” me into essential emergencies. So, for example, when I confront the works of Néle Azevedo, Mandy Barker, and Michael Sailstorfer, who create works out of melting ice, ocean pollution, and trees, we are thrust into environmental emergencies caused by global warming, ocean pollution, and deforestation. The same occurs with the “social paradoxes” generated by the political, financial, and technological frames that contain us: the “urban discharge” of slums and plastic and electronic wastes and the “historical accounts” of invisible, ignored, and denied events. These are not addressed properly in the public realm and have become essential emergencies.

Q: And in addition to the aesthetic examination, how do you document the nature and history of each emergency?

SZ: There is a lot of research behind my discussion each emergency, and I rely on the work of renowned economists, political scientists, and investigative journalists. In the case of social media, represented by Filippo Minelli’s Contradictions series, the investigations of Jose van Dijck, Lev Manovich, and Evgeny Morozov were very useful as they also indirectly explained how the artist’s work emerged in the first place. I also use the work of the political scientist as Georg Sorensen, the urban theorists David Harvey, and the historian Ilan Pappé. The reconstruction of these emergencies through renowned thinkers allows the reader to see how serious the concern of the artist is. If truth in art has become more important than beauty, as Arthur C. Danto once said, its because artists “have become what philosophers used to be, guiding us to think about what their works express. With this, art is really about those who experience it. It is about who we are and how we live.”

Part II of the interview will appear tomorrow.