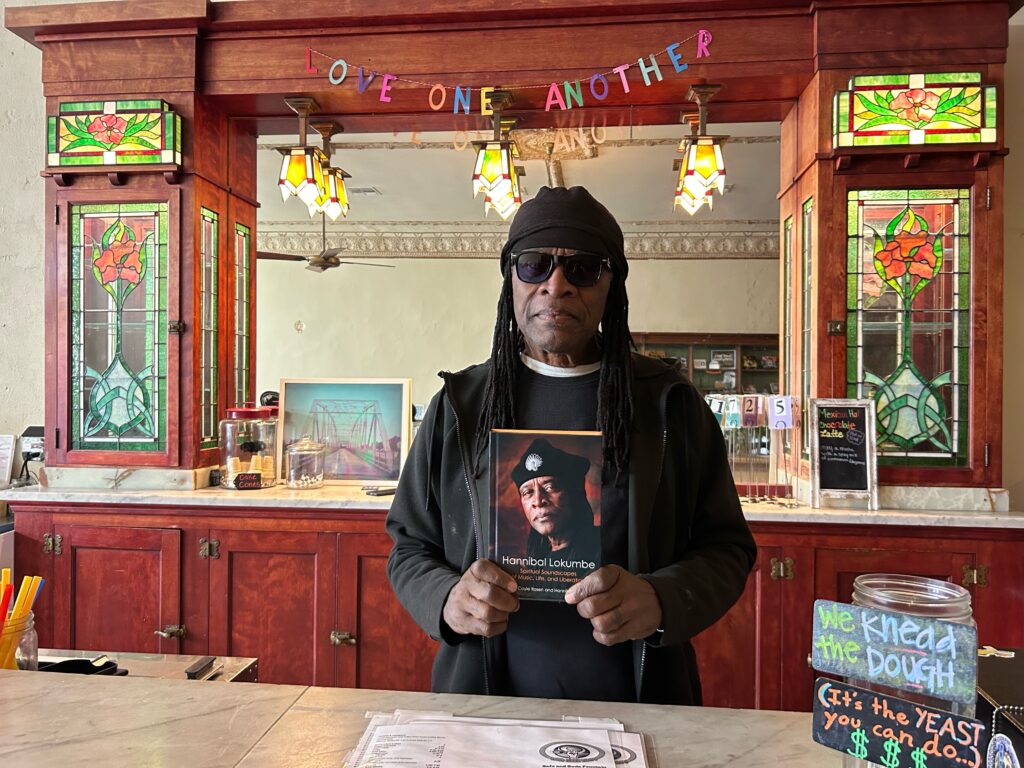

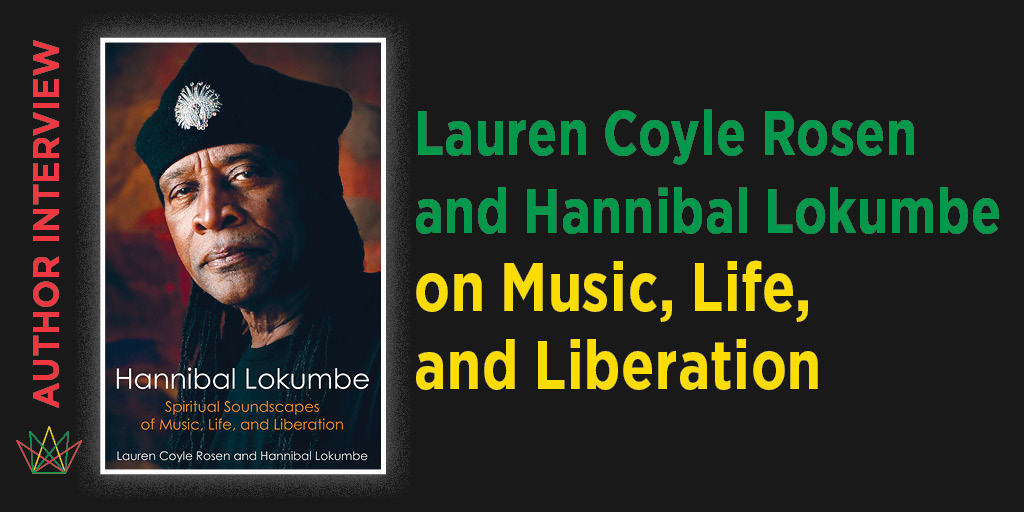

Lauren Coyle Rosen and Hannibal Lokumbe on Music, Life, and Liberation

For Hannibal Lokumbe, music is a profound source of spiritual liberation. A pathbreaking orchestral composer and visionary jazz musician, Lokumbe composes resonant works that give voice to the freedom struggle of the African diaspora, the broader African American experience, Indigenous histories, and humanity. In this exchange, coauthors Lauren Coyle Rosen and Hannibal Lokumbe reflect upon the creative process and publication of their recently released book, Hannibal Lokumbe: Spiritual Soundscapes of Music, Life, and Liberation.

Lauren Coyle Rosen: You mentioned that many things have come into clearer view for you, following the completion of this book.

Hannibal Lokumbe: I think that it was such a perfect time to do the book for me, personally. I think this because I’ve never had one semblance of doubt about it being the right thing to do at that particular time. When I look at the result, at what has happened because of it, I see clearly that it’s something that I needed more than I realized, so that I could achieve my next level of existence.

Now, without the amount of pain and suffering and memories of inhuman things that I had before, I’m able to walk by Lock Drug Store [in Bastrop, Texas] and peek my head in and get a glass of water or soda and give my regards and receive warm wishes. For seventy-plus years, each time I walked by that space, my body and my spirit were transported back to that horrific experience I had there [a racist attack from a woman who worked there] at five years of age. That was the first real, authentic instance where my humanity was set upon and set alight.

Had the book not been done, I’m sure I would still be in the same place I was before the book was created, before the book was presented in that very space. And, I dare say, my heart and soul were not the only ones that were radiant, freed of a lot of trauma, a lot of pain.

Coyle Rosen: Did your experience significantly change after you did the reading aloud in Lock Drug Store?

Lokumbe: Yes. It began when I had the courage enough to approach the current owner. She had known the story. I asked her if I could do the reading there. The first healing began with her reaction, which was to be overcome with emotion and weep for an extended period of time. It was clear to me in her weeping that the ancestors were correct in giving me the courage to approach her and to rectify, in that very space, by reading from our book what I had experienced. And this further proved that, whenever we are forgiving, the first beneficiary of that forgiveness is ourselves.

Coyle Rosen: And that’s a central Music Liberation Orchestra principle, right? The commitment to forgiveness?

Lokumbe: Yeah, that’s right! [Playing with jubilation on the piano.]

Coyle Rosen: Was it the same kind of alchemy you experienced when you bought the old gas station—the one where the white owner wouldn’t let you enter or use the bathroom when you were a kid—and you turned it into your current music studio?

Lokumbe: The exact same. And around the same age as well.

Coyle Rosen: I remember you said that you had never told your mother what had actually happened with the attack in the soda shop. You just told her you wanted to go to the river, and you didn’t want ice cream after all.

Lokumbe: Yeah, I couldn’t do that to her. I couldn’t hurt her like that.

Coyle Rosen: Has she shared a healing and a peace that she also has experienced, from spirit, now that you’ve done the reading there?

Lokumbe: Yes, clearly. And in her visitations. But I’ve come to realize that my mother saw and knew things that were not immediately obvious. And the longer I live, the more I realize the truth of that. It’s not as though you suffer in silence, but more so that you, in silence, trust the perfection of things and of yourself. So, there’s no need to cry out every time your soul is pierced with hatred or with sickness or with fear. I’m convinced this is right, because it helps you to realize that you’re never really alone. Generally, people who are spiteful and hateful, they don’t realize that they are not alone. So, I was able to keep my mother from the horror that I felt because I was so well loved. And when you are loved to that degree, you do as best you can to keep all atrocities possible from those you love.

It’s fascinating, too. In reviewing many of my scores, I always see what I felt from my mother. And that was: life is one extraordinarily miraculous divine gift. That’s why she could help so many people. That’s why Jesus could help so many people, and Trane [John Coltrane] and Billie Holiday. It’s like, you can’t help it.

Coyle Rosen: I was thinking about how you recently reached out to Miles [Evans] and Noah Evans, and to me. You mentioned to us how Gil Evans had just helped you resolve something with your composition in the dream state. Now that you’ve put a lot of your life journey down in book form, has it changed at all, how you interface with those who have crossed over [to spirit], in the music?

Lokumbe: Yes, it’s the same thing. How could a document such as that not affect everything about me and everything that I do, everything that I desire to do in a way that I desire to do it, which always ends up being like the universe—a sense of expansion, a sense of spiritual and physical expansion. So, in my current opera, Once a Place Called Earth, I realized that, in that text, was what the spirits were leading me to do before I approached the lady at Lock Drug Store. That’s the intrinsic power of music. Often, it shows me things that are five, ten years down the line. Yet to come. I see that in every work that I’ve done. I always see where I’m being prepared to do the next work.

Coyle Rosen: One of the things that I cherish so much about this book is how you directly speak to the interconnectedness of everyone and everything, and how everyone has this inherent divine connection in them.

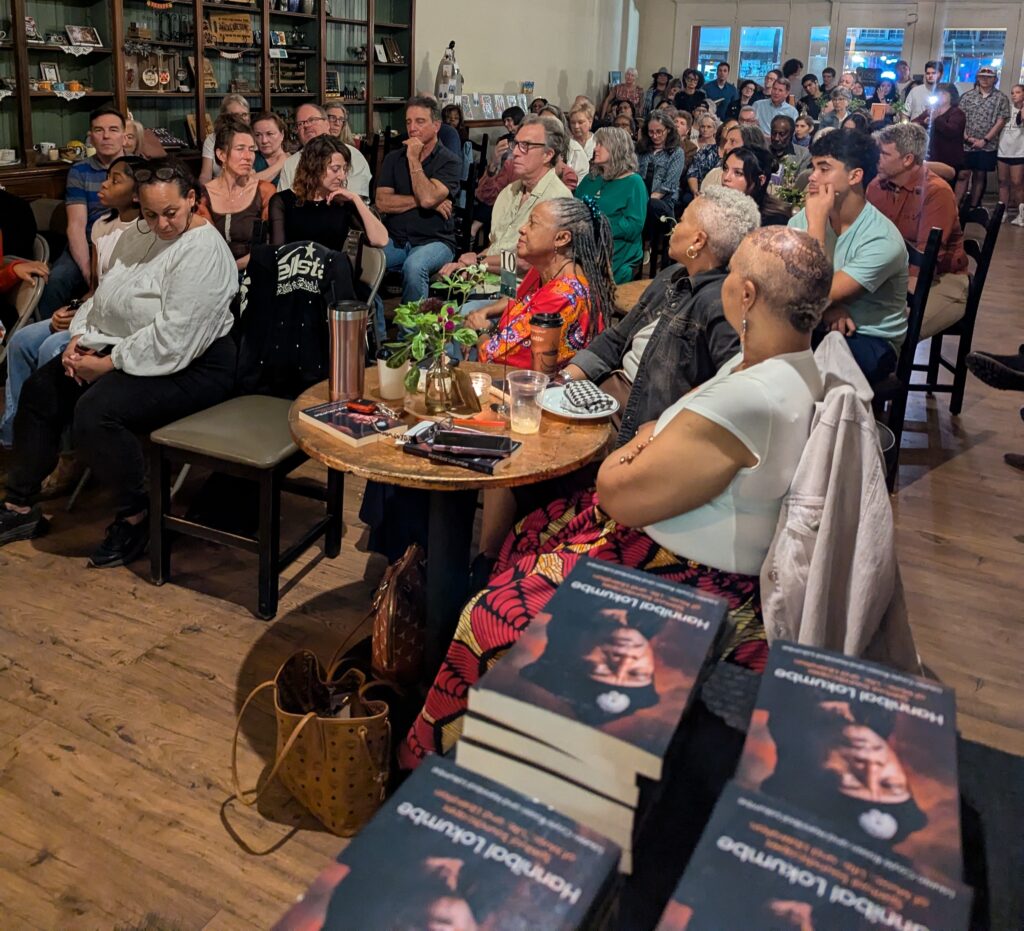

Lokumbe: People feel it, too. I mean, in every space. For example, in Texas City [Hannibal’s hometown], when I read “Oracle” from the book, it was astonishing – the feeling in the space. To be reading something that is so familiar in people’s lives. That was a moment of just sheer—I would imagine, in a way, it’s like the Big Bang. [laughs]

One of the musicians who was in the Texas City High School Band, he stood and said, “I’m Ron. And we played in the band at the same time together, Hannibal. And I always knew that your work would help people because, whenever you would stand and play your solo, it gave me, and it gave the people, a sense of relief and a sense of hope.” It was very powerful. He said, “I was privy to many racist conversations at the school with people I knew. And I found it extraordinary, how you seemed to not be affected by it. But now, I understand that it was the music that took care of you and kept you from turning towards hatred and retribution.”

This reading was in the Moore Memorial Public Library—one which, like here in Smithville [Texas], I and other people of Jonah were not allowed to enter. It’s unbelievable. The readings so far have been like a campaign of liberation.

Creating this book has made me feel more connected to everything, because the journals and my compositions are where the essence of me lies. I’m honored and at peace knowing that the book provides to humanity what I desired to provide.

Coyle Rosen: And how would you describe it?

Lokumbe: My adjective would be liberating. Well, on my horn is [inscribed] “liberation.”

I’m so thankful that we were able to include that quote from Pheta [the Aura/Fire, a figure in Hannibal’s Once a Place Called Earth opera] at the end:

“Soon Being, you will come to know that you are the God and the Gods you seek to worship and praise, and you are the devil and the demons you fear and curse. And in you lies the power to choose which you will be. And as you have chosen, so shall you be.”

Humans, we are miraculous mirrors. As the sea reflects sunlight, our actions and words can reflect. People can reflect upon them. People can be moved by them to the degree that they see how intricately woven we all are. Whenever I’ve mentioned that passage, it’s like, all of a sudden, the people can see, “Okay, this came from another human being who has legs like me, who has bills like me, and joy and tribulations like me. So, then, it’s not impossible that I’m the essence of what he just said. I could possibly be the divine, or I could possibly be the beast.”