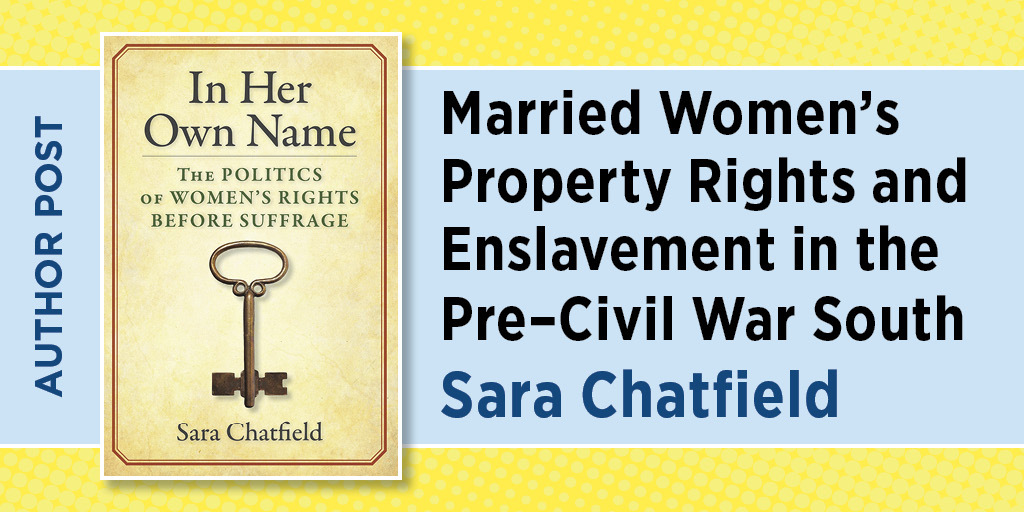

Married Women’s Property Rights and Enslavement in the Pre–Civil War South

Sara Chatfield

When we think about women’s history, the suffrage movement is often one of the first topics that comes to mind. But individual states, largely before women had the right to vote, enacted reforms that significantly expanded the economic rights of married women. Beginning in 1835 and continuing through 1920, U.S. states passed laws that granted married women new rights to own and control property. As I discuss in my forthcoming book In Her Own Name: The Politics of Women’s Rights Before Suffrage, these new laws were used by male politicians for a wide variety of purposes. One of the main takeaways of the book is that male elites were able to use these reforms to achieve goals that often had little or nothing to do with women’s empowerment, and those goals varied a lot depending on both the region and time period.

Today, I’ll explore one of these region- and time-specific purposes of married women’s property acts. In the pre–Civil War South, these reforms played a particular role of upholding the institution of slavery by including special provisions relating to enslaved humans owned by married white women. At least five slave states—Mississippi, Maryland, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Texas—explicitly identified enslaved people in their married women’s property laws, often treating enslaved people differently from other sorts of property. Even where slave states did not explicitly list enslaved human property in laws relating to married women, those laws still had important implications for slavery.

At least five slave states—Mississippi, Maryland, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Texas—explicitly identified enslaved people in their married women’s property laws, often treating enslaved people differently from other sorts of property.

For one thing, southern white women were especially likely to hold enslaved people as property as compared to other types of property. Slave-owning parents were especially likely to “gift” enslaved people to their daughters, and enslaved people were perceived as easier for women to control than other types of property, such as land. If you’re interested in learning more about white women slave owners, I highly recommend Stephanie Jones-Rogers’s recent book, They Were Her Property.

In addition to being perhaps the most significant form of property brought to marriages by white women, enslaved people also played central roles in southern credit markets. Slave owners saw many benefits to the use of enslaved people as collateral for loans, and most southern states that passed married women’s property laws before the Civil War included a debt-relief component in those laws. These provisions stated that a wife’s enslaved human property could not be seized to pay her husband’s debts but often also guaranteed that the husband would have control over the labor of these people as well as ownership of profits from their labor. Thus, these laws provided a continuing revenue stream and economic stability to white slave-holding families during a time of economic turbulence.

Mississippi’s 1839 statute illustrates some of the dynamics at play. Four of the five provisions of the statute deal explicitly with enslaved human property. These sections of the law gave wives ownership over enslaved people they brought into a marriage, exempted this property from their husbands’ debts, and gave control, management, and profits to the husbands. You can view two of these sections from Mississippi’s 1839 statute book here:

Even after the Civil War, when married women’s property acts were written using race-neutral language, they still had effects on racial patterns of property holding. On a basic level, laws protecting the property of married women were beneficial only to women who had property to protect. Around the country, state laws relating to property, land, and marriage differed, but in general white women were most likely to bring property to their marriages, and thus they were the most likely to benefit from the new reforms.

Both formal laws and informal practices around the nation made it more difficult for Black citizens to purchase land and obtain homesteads, and Native people were being stripped of their lands through the settlement of the West. Together, these laws and practices made it less likely that Black and Native women would hold property, especially land, after marriage. State courts in states with laws prohibiting interracial marriage also became increasing likely to deny inheritance rights to Black and Native widows and multiracial children in favor of white relatives. Although the particulars differed between states and regions, the constellation of state laws and policies added up to a system in which white married women were granted substantially greater protection of property by state governments than were Black and Native women. Married women’s property laws were ultimately just one piece of this bigger picture.

Sara Chatfield is assistant professor of political science at the University of Denver and the author of In Her Own Name: The Politics of Women’s Rights Before Suffrage.