A Soviet Futurist in Beijing Sergei Tretyakov’s Internationalist Aesthetics Edward Tyerman

Edward Tyerman

“You are travelling to Beijing. You must write travel notes. But not just as notes for yourself. No, they must have social significance.”

These are the opening words of “Moscow—Beijing,” a 1925 travel sketch written by the Soviet writer Sergei Tretyakov. An immensely talented poet, playwright, journalist, and theorist, Tretyakov has long lain in the historical shadow of his more famous friends and colleagues from the interwar avant-garde. My book Internationalist Aesthetics: China and Early Soviet Culture, the first book-length study of Tretyakov’s work in English, places him at the center of a crucial but understudied period of intense Soviet engagement with China in the 1920s and 1930s. Tretyakov’s attempts to produce cultural forms that could mediate an internationalist Sino-Soviet relationship constitute a vital experiment in socialist aesthetics and an important precursor to many of the insights of postcolonial studies.

A Futurist poet whose first publications appeared in Vladivostok during the Russian Civil War, Tretyakov became a key member of the Left Front of the Arts, or LEF—a collection of avant-garde artists who sought to align their work with the task of creating a new, postrevolutionary culture. Publishing in the journal LEF alongside such luminaries as Vladimir Mayakovsky, Dziga Vertov, and Alexander Rodchenko, Tretyakov emerged as one of the group’s major theorists. His account of socialist art and the socialist artist as actively engaged in the transformation of social life profoundly influenced contemporaries like Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht. In the theater, his scripts were staged by Vsevolod Meyerhold, the doyen of the Soviet revolutionary stage, and a young Sergei Eisenstein. Tretyakov also collaborated with Eisenstein in the cinema, co-writing the intertitles for Battleship Potemkin, perhaps the most famous Soviet film of the 1920s. The two even planned to shoot a trilogy of films about China in 1926, though sadly the project never got past the planning stage. By that time, Tretyakov’s own work was profoundly bound up with the Soviet relationship with China.

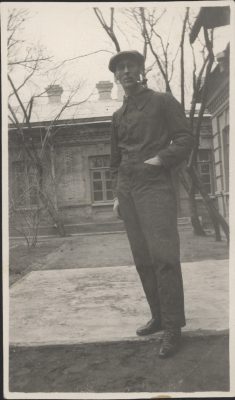

In 1924, Tretyakov travelled with his wife and child to Beijing, where he would spend eighteen months teaching Russian at Beijing University. While there, Tretyakov published around fifty articles about contemporary China in a dozen Soviet newspapers and journals. His stay in Beijing coincided with a moment of heightened Soviet investment in China’s domestic politics. The Soviet-led Third Communist International (Comintern) sponsored an alliance between the Chinese Nationalists and the Chinese Communists in the hope that a revolution would eject Britain and other imperialist powers from their positions of economic and political power in the country. At the same time, this was a moment of enormous intellectual and political ferment in China. The New Culture Movement of the 1910s and the May Fourth Movement of the 1920s had generated a profound reevaluation of tradition and a search for viable forms of cultural modernity. Tretyakov’s colleagues at Beijing University included Li Dazhao 李大釗, one of the pioneers of Chinese Marxism, and Lu Xun 魯迅, the pre-eminent Chinese writer of the period and a keen reader and translator of Russian literature. Tretyakov even helped Lu Xun complete a translation of Alexander Blok’s famous poem of the Russian Revolution, The Twelve. There was a growing interest in the Soviet experiment among Chinese intellectuals and revolutionaries, and several of Tretyakov’s students in Beijing would go on to study in the Soviet Union.

Tretyakov sought to position himself as a mediator between these two worlds: the postrevolutionary society taking uncertain shape in the Soviet Union, and the politically unstable, intellectually dynamic China of the 1920s. The problem, as he diagnosed it, was that no one in the Soviet Union knew very much about contemporary China. Though Soviet newspapers constantly exhorted their readers to feel a sense of solidarity with the revolutionary struggles of their Chinese comrades, most people’s perceptions of China were trapped in exotic stereotypes. Tretyakov provides an ironic summary of these stereotypes at the beginning of his 1925 essay “Loving China”: “A mysterious country. An inscrutable people. Chinese porcelain. Chinese shadows. Chinese silk. Chinese tea. The Chinese wall. Chinese writing. Chinese umbrellas. . . . This is the knowledge of China held by ninety percent of our average men-in-the-street.” He argues that his readers will only come to “love” China when they understand that country as inhabiting the same present moment as themselves, a disruptive time of uneven and even violent modernization with the potential for revolutionary transformation. For Tretyakov, this required documentary accounts of contemporary China that could adequately express its shifting and unstable reality to a Soviet audience.

What is so striking about Tretyakov’s writings on China is the way that he places this tension between egalitarian solidarity and hierarchical leadership at the heart of his own work.

Beyond his journalistic articles, Tretyakov experimented with new documentary forms in his attempts to link China and the Soviet Union. His Futurist poem “Roar China” used onomatopoeia to capture the sounds of Beijing street peddlers and highlight their exploitative economic conditions. A documentary play with the same name, Roar, China!, premiered at Meyerhold’s theater in Moscow in 1926. Based on a recent incident in Sichuan, where a British naval captain had compelled the execution of two Chinese boatmen accused of murdering an American businessman, Roar, China! went on to achieve global success, with high-profile productions in Germany, New York, Japan, and China itself. Most originally of all, Tretyakov worked with one of his Beijing students, an aspiring writer named Gao Shihua 高世華, to produce a collaborative account of Gao’s life. This experiment in co-authorship, which Tretyakov called a “bio-interview,” appeared in print under the pseudonym Den Shi-khua, and offered Soviet readers an extensive account of contemporary Chinese society as seen from the perspective of a single young life.

Central to Tretyakov’s work on China, as well as to the project of socialist internationalism itself, was the question of authority. The Comintern, founded by the Bolsheviks in 1919, explicitly set itself the task of expanding the scope of world revolution beyond Europe and North America to encompass the anti-imperialist struggles of the colonized world. This expansion of the revolutionary project held out the possibility of decentering Europe and overcoming the civilizational and racial divides produced by imperialism, providing a framework for European and Asian communists to fight together in a common struggle. At the same time, however, the activities of the Comintern became increasingly subordinated to Soviet control, which led to a prioritizing of Soviet theory, Soviet experience, and Soviet interests.

What is so striking about Tretyakov’s writings on China is the way that he places this tension between egalitarian solidarity and hierarchical leadership at the heart of his own work. Tretyakov constantly reflects on the nature of his own role as a Soviet mediator of China, flagging up his limitations as an outsider with limited knowledge of Chinese even as he asserts his privileged capacity to interpret China’s revolutionary reality as a veteran of the Russian Revolution. His claims to analytical insight or artistic veracity are undercut by constant reminders of his own dependence on Chinese mediators and imperfect processes of translation. These meta-reflections reach a kind of apotheosis in the bio-interview Den Shi-khua, produced from a series of interviews between Tretyakov and his former student Gao over a period of six months. This 300-plus-page book ends not with revolutionary triumph, but with confusion and uncertainty. Gao returns to China, Tretyakov loses touch with him, and another student suggests that much of what Gao told his former teacher may have been lies. Tretyakov’s book coincided with the defeat of Soviet policy in China; the Chinese Nationalists turned on their Communist allies in 1927 and drove Soviet advisers out of the country. But Tretyakov turned defeat into a new method, insisting that a mode of aesthetic production that seeks to be truly internationalist must also be one that questions its own grounds of authority, the limits of its knowledge, and its right to represent the other.

Edward Tyerman is an associate professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of Internationalist Aesthetics: China and Early Soviet Culture.