Russian Literature Week 2019

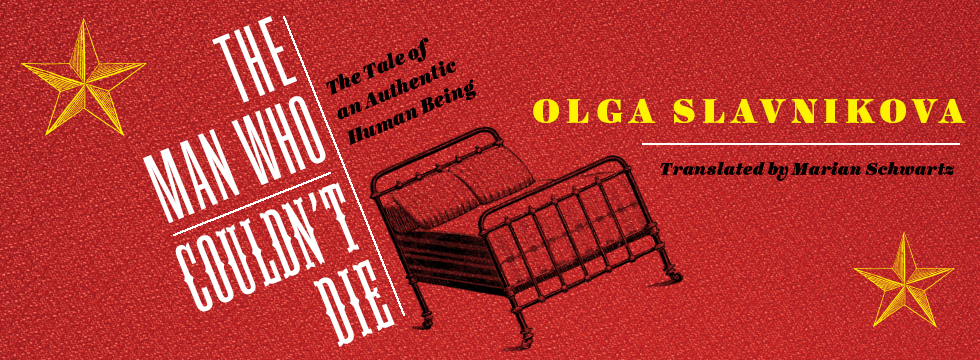

It’s Russian Literature Week! All week (May 20-24) there will be events with acclaimed Russian authors, famed translators, and leading scholars and critics celebrating Russian literature. We’re bringing the #RussianLiteratureWeek celebration online by sharing excerpts throughout the week from our Russian Library series. Today we are sharing an excerpt originally published in Lit Hub from The Man Who Couldn’t Die, a novel by Olga Slavnikova, translated by Marian Schwartz, that tells the story of how two women try to prolong a life—and the means and meaning of their own lives—by creating a world that doesn’t change, a Soviet Union that never crumbled.

Among this year’s Russian Literature Week festivities, there will be discussions of the novel The Man Who Couldn’t Die in New York, DC, Philadelphia. If you are in New York City, join us for an event this evening at the Grolier Club at 6:30 pm with author Olga Slavnikova, translator Marian Schwartz, and poet / translator Ian Dreiblatt.

• • • • • •

The Man Who Couldn’t Die by Olga Slavnikova, translated by Marian Schwartz

It had been Marina’s idea. Keep Alexei Afanasievich from finding out about the changes in the outside world. Keep him in the same sunny yet frozen time when the unexpected stroke had cut him down. “Mama, his heart!” Marina had pleaded, having grasped instantly that, no matter how burdensome this recumbent body might be, it consumed far less than it contributed. Initially, clear-eyed Marina may have been moved by more than primitive practicality. There had been a period of infatuation between her and her stepfather, when the little girl would crawl all over Alexei Afanasievich, who seemed as big as a tree to her. She would go through all his pockets and invariably find chocolates planted there for her. Alexei Afanasievich taught her how to fish and how to toss plywood rings on a post. Once the two of them had cleaned out every last gaudy toy with the digger claw on a Czech grab-n-go.

All that lasted about a year. For a while, the dragonfly pond out back of their brand-new nine-story apartment building had sucked on their two red-and-white fishing floats as if they were pacifiers; by the next summer, the pond had turned into a swamp plastered poison green with plants—and now there were stalls on the spot. Marina couldn’t forget this entirely, at least not until that rather bizarre moment when, a month after Brezhnev’s television death, she hung a medal-strewn, beetle-browed portrait of that official paragon on the wall.

In retrospect, Nina Alexandrovna could only wonder at young Marina’s perspicacity. You’d think she had nothing on her mind beyond Seryozha and her synopses. Yet, at the first historic tremor, she had divined in the decrepit general secretary’s replacement by a younger, more energetic one not a pledge of Soviet life’s continuity but the beginning of the end. She immediately began preserving the substance of the era for future use and purging it of any new admixtures, no matter how harmless they seemed at first. . .