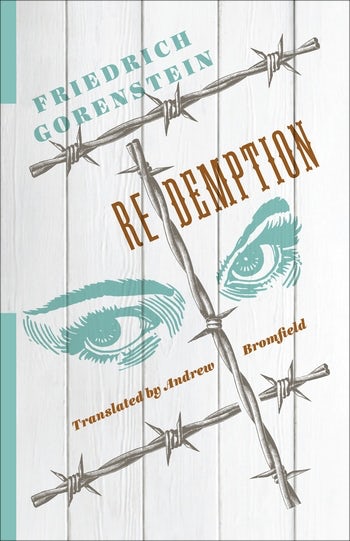

Is Friedrich Gorenstein’s Redemption a Holocaust novel?

“Set immediately after World War II in a Soviet town emerging from German occupation, Friedrich Gorenstein’s Redemption is a small masterpiece of post-Holocaust fiction.”

~ Val Vinokur, The New School

This week we are featuring Redemption, by Friedrich Gorenstein and translated by Andrew Bromfield. Today, we are featuring an analysis of the book by Sandra Chiritescu, PhD Candidate in Yiddish Studies at Columbia University.

Enter our drawing for a chance to win a free copy of the book!

• • • • • •

As a student of German and Yiddish literature it is unavoidable to grapple with Holocaust history and literature. One inevitably develops a sense for the different modes of representing the “unrepresentable” or “unspeakable,” and for the variety of ways in which Holocaust testimony and memory penetrate texts, films, and interviews throughout the decades. Nonetheless, Friedrich Gorenstein’s Redemption startled me in a way that made me reexamine what I consider to be the boundaries of the Holocaust literature genre.

With the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht looming large this past November, Holocaust commemorations across the country and globe became even more visible than they have been since the Eichmann trial in 1961 broke through silence on the matter. Considering the prominence – popularity, even – of Holocaust stories in popular media and in the public consciousness, we might think we know exactly how to delineate what does and what does not fall under the umbrella of the term “Holocaust”: Auschwitz, Anne Frank, Poland, Nazis, Jewish extermination – absolutely. Such a subset of figures, sites and names has become definitively linked with the event we call the Holocaust, serving as a shorthand for an expansiveness that may often seem too overwhelming to comprehend and render intelligible.

In its categorization and cataloging efforts the Library of Congress has settled on the subject heading “Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)”, thus giving us a framework whose definite borders a novel such as Redemption questions. The novel was originally written in 1967 in Russian and its plot is set a few months after the end of World War II, right around New Year’s Eve 1945. The basic premise of the novel is a love affair between the teenage protagonist Sashenka – who also informs on her mother with the police – and a Jewish soldier returning home to give his family members a proper burial. The unfolding of this plot is, of course, inextricably linked to what had happened in the small town (perhaps Berdichev where Gorenstein grew up?) in the preceding years.

“The question, then, of what comprises Holocaust literature is equally difficult to settle.”

Our certainty about the temporal and geographical limits of the Holocaust is easily challenged and the terrain we had felt so secure on becomes muddy very quickly. What about the Holocaust in the Soviet Union? Or the Holocaust in North Africa? Murder beyond the gas chambers? Jews in German DP-camps? Pogroms against Jews returning to their Polish hometowns? Holocaust or just Holocaust-adjacent?

One outgrowth of these palpable uncertainties are such – often unnecessarily vicious – debates as: Who is a Holocaust survivor? Anyone who spent time in a concentration camp, ghetto or in hiding? Those who fled in time but remained physically unharmed? The stakes of these debates are, naturally, not merely semantic: at a time when the number of living survivors is rapidly dwindling, holding on to demarcations becomes ever more important. The author Friedrich Gorenstein is, perhaps, an ideal example in this regard. Gorenstein was born in 1932 in Ukraine, his father was killed in a gulag in 1935, and he and his mother fled Berdichev in 1941 heading to Orenburg in the Urals. There his mother died of tuberculosis. Like many Soviet Jews, Gorenstein thus survived the Holocaust by fleeing deep into the Asiatic parts of the Soviet Union where he remained physically unharmed by Nazi violence but plagued by hunger and deprivation. This lesser-told story of survival sits at the margins of what we often consider a typical survivor narrative and shifts our conception of Jewish survival in Eastern Europe.

The question, then, of what comprises Holocaust literature is equally difficult to settle. A broad and inclusive working definition of what we might consider Holocaust literature is proposed by scholars David Roskies and Naomi Diamant in their volume Holocaust Literature: A History and Guide: “Holocaust literature comprises all forms of writing, both documentary and discursive, and in any language, that have shaped the public memory of the Holocaust and been shaped by it.” How, then, does Gorenstein’s Redemption fit or challenge these criteria?

“Gorenstein’s novel complicates our notion of Holocaust literature not only because it is set in late 1945 and early 1946 – after the end of World War II – but also because it lacks what we might think of as “Holocaust staples” . . .”

Gorenstein’s novel complicates our notion of Holocaust literature not only because it is set in late 1945 and early 1946 – after the end of World War II – but also because it lacks what we might think of as “Holocaust staples”: there are no Nazis, no ghettoes or concentration camps and the only Jewish character is a Red Army soldier returning from the front. Again, the uncertainty whether he might be considered a Holocaust survivor pushes us to think about questions of victimhood and survival beyond a Nazi versus shtetl-Jew binary.

Nonetheless, there are Jewish victims in this novel: namely, the soldier’s family to whom he returns in order to give them a proper burial. But the circumstance of their murder lies outside of what we generally conceive of as the Nazi genocide of Jewry. The Jewish family is murdered by their neighbor, the motive remains unclear: anti-Semitism? Greed? Anger fueled by the difficult living conditions during war-time? The matter is further complicated by the fact that the murderer is not a German Nazi or even a Ukrainian, thus undermining any expectations we may have had of a story about a local nationalist encouraged to collaborate with Nazis in the extermination of Jews. The murdering neighbor is, in fact, an Assyrian, part of a small minority in Ukraine in the 1940s who themselves fled the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. We learn no other details about the perpetrator, or the victims, for that matter, and are thus left with a universalized perspective on Holocaust violence and atrocities: there is a primal and inexplicable core to murder, and pure love can fuel forgiveness which overcomes despair and lust for vindication.