Book Excerpt! How to Read Chinese Poetry in Context

On Saturdays throughout National Translation Month we have been featuring poetry titles. Continuing this week’s theme of Chinese literature we have an excerpt from How to Read Chinese Poetry in Context edited by Zong-qi Cai. The book is latest addition to the “How to Read Chinese Literature” series, a series of innovative guided anthologies that join language acquisition with the study of literature and culture.

The excerpt below focuses on the prominent Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu, a poet whose work we have also published in The Selected Poems of Du Fu translated by Burton Watson

• • • • • •

Du Fu: The Poet as Historian

By Jack W. Chen

The Tang dynasty (618–907) was notable for its great political, economic, and cultural achievements, which rivaled the heights of the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and provided a model for later dynasties to emulate. At the same time, the historical memory of the dynasty was inextricable from the An Shi Rebellion, which spanned the years 755 to 763, brought about the death of possibly millions of people, and almost ended the dynasty. For traditional historians, the key actors at the heart of this event were the Emperor Tang Xuanzong (r. 712–756); the beautiful Yang Yuhuan (719–756), often referred to as “Prized Consort” (Guifei); the Turko-Sogdian general An Lushan (ca. 703–757) and his childhood friend Shi Siming (703–761); and the reviled prime minister Yang Guozhong (d. 756). The blind infatuation of Xuanzong for Yang, the Prized Consort, and the bitter enmity between An Lushan and Yang Guozhong, would result in a historical trauma that marked the political decline of the Tang over the next century and a half.

Although the events of the rebellion were commemorated in a host of literary and historical writings, no single writer has been as closely identified with this moment in Chinese history as the famed Tang poet Du Fu (figure 15.1). Du Fu (712–770) was born to a distinguished official family in the capital region of Chang’an. He was unsuccessful in his early attempts to pass the civil service examinations and only secured an official appointment by submitting three rhapsodies to the emperor. However, before he could take up his new position, the An Shi Rebellion broke out, causing Xuanzong to flee to Sichuan and Du Fu to embark upon a lifetime defined by sometime employment and much wandering.

He wrote many poems over the course of his life, and while many of them celebrate the private aspects of family life or address personal moments of happiness, the critical reception of Du Fu has often emphasized his role as a witness to the age, cementing his image as “poet-historian” (shishi). This is noted as early as the second part of the Tang dynasty, by the anecdotist Meng Qi (fl. 841–886), who wrote, “Du Fu met with the An Lushan disaster and wandered in exile through Longyou and Shu. He set it all forth in his poems, and by parsing the lines, one can understand his underlying intent. There was perhaps nothing that he omitted, and thus his contemporaries referred to him as the ‘Poet-Historian’ ” (LDSHXB 15). The sobriquet Poet-Historian would be repeated in Du Fu’s biographical entry in the New History of the Tang Dynasty (Xin Tang shu) (XTS 201.5738) as well as by numerous later scholars in the following centuries.

Yet it should be noted that Du Fu’s acts of witnessing were never simply reportage but were born of a combination of historical reference, personal experience, and literary invention. The sense of historical realism that later readers have noted in Du Fu’s testimony was more than just a reflection of the hermeneutical expectations of traditional Chinese literary culture; it was also the product of Du Fu’s extraordinary poetic imagination, of his compelling powers of vivid description. Du Fu reimagined his wartime experiences through poetry, and the fidelity of his representations was not to historical facticity as much as to the truth that could paradoxically be accessed through the fictive strategies of literary form.

This productive tension between historical experience and literary representation informs the poems that are now collectively known as “The ‘Three Officers’ and ‘Three Partings’ Poems” (“Sanli sanbie shi”) (DSXZ 7.523–539; QTS 217.2282–2285). Each of these poems takes the form of a vignette—a brief, evocative, anecdotal narrative. In this way, Du Fu is able to represent the broader sweep of the An Shi Rebellion, which was complex and not easily reduced to linear narrative, within the more manageable scale of exemplary individual experience. Du Fu’s poetic vignettes provide compelling specificity, the sense of personal drama, and the human stakes, locating the vast consequences of the event within accounts of a telling moment or encounter.

The “Three Officers” Poems

We begin with the “Three Officers” poems. The first poem of this set, “The Officer at Xin’an” (“Xin’an li”), has a short preface attached to it: “Composed after retaking the capital. Though the two capitals have been retaken, the rebels still flood the lands.” Traditional and modern scholars have latched on to this detail, along with other historical references made in the poems, to identify a date of 759 for composition of the set. The retaking of the capitals in that year was without question a significant turning point in the rebellion, though the war was far from over.

Some historical context is useful to understand the background to the poems. The emperor was by that point Tang Suzong (r. 756–762), who had claimed the throne in 756, shortly after his father, Xuanzong, had decamped to Sichuan. An Lushan had died in 757, assassinated by his own son, An Qingxu (d. 759), who carved open his bedridden father’s belly, spilling his guts on the floor. By the end of 757, the Tang forces had succeeded in retaking both Chang’an and Luoyang, and were increasing pressure on the rebels, who had split into two main factions, one led by An Qingxu and the other by Shi Siming. In 759, An Qingxu was in danger of being captured by Tang forces, when Shi Siming came to An Qingxu’s rescue, defeating a vastly larger imperial army commanded by Guo Ziyi (697–781) at Yecheng. Shi Siming then executed An Qingxu, ostensibly for the crime of patricide.

Nevertheless, what immediately concerns Du Fu is not so much the grand theater of imperial disaster but the small-scale hardships that take place in the lives of the ordinary people. After all, the sufferings of the commoners would continue, no matter who was victorious on the dynastic level. The ongoing troubles of the rebellion therefore become the backdrop to Du Fu’s real focus: how the wartime circumstances were experienced within the domain of the ordinary, at the level of the human.

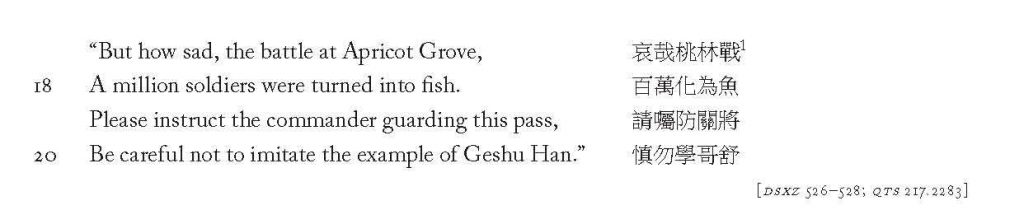

I will begin somewhat out of order with “The Officer at Tong Pass” (“Tongguan li”), the second poem of the “Three Officers” poems, which differs significantly from the other two in theme and in terms of historical context. Here, Du Fu encounters an officer in charge of rebuilding the defensive structures at Tong Pass, the fortification that the Tang general Geshu Han (d. 757) had commanded. Although Geshu Han counseled patience and caution, believing that the best strategy would be to outwait An Lushan and allow dissension to arise among the rebel troops, the prime minister, Yang Guozhong, insisted that the general lead the troops out of his strategic position and engage with the rebels on open ground. Having no other choice, Geshu Han went to meet the rebels in battle, and the resulting battle was a disaster for the Tang army. The rebels not only seized Tong Pass but also captured Geshu Han (who was handed over by his own soldiers).

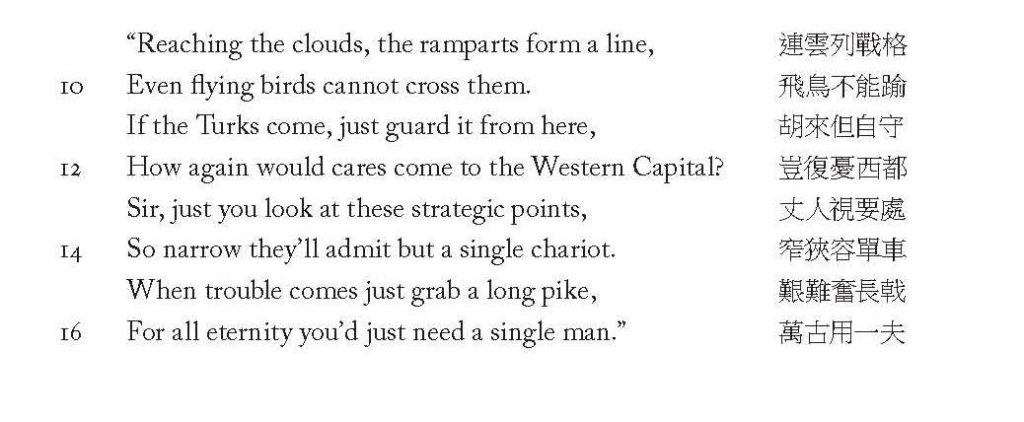

In the poem, Du Fu begins by describing the bustling scene of construction and the impressive height of the fort’s walls. He then asks the officer whether the defenses will ward off barbarian invaders. The officer replies:

The officer’s confidence is born of the technological intelligence built into the fortifications. The soldiers who man the fort are almost an afterthought; all that is needed is one man with a long pike. Yet, as Du Fu points out in his response:

The main problem, as Du Fu notes, is that even the most cunningly designed fortification may be undone by unwise commanders. His rejoinder to the officer shifts between rumination and direct address, ending with a reminder that Geshu Han, too, once thought his position safe. Du Fu is a humanist, and thus it is the man who matters most of all to him, more than any cunning strategy or technical savvy. Baldly didactic in ways that the other two “Officers” poems are not, “The Officer at Tong Pass” reads more like a parabolic scene of instruction.

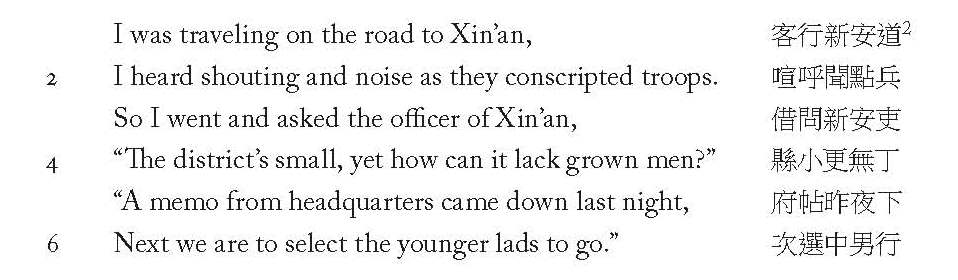

The thematic and tonal difference is not immediately evident in the opening lines of the first poem of the set, “The Officer at Xin’an,” which begins with Du Fu meeting an officer in charge of the conscription of troops:

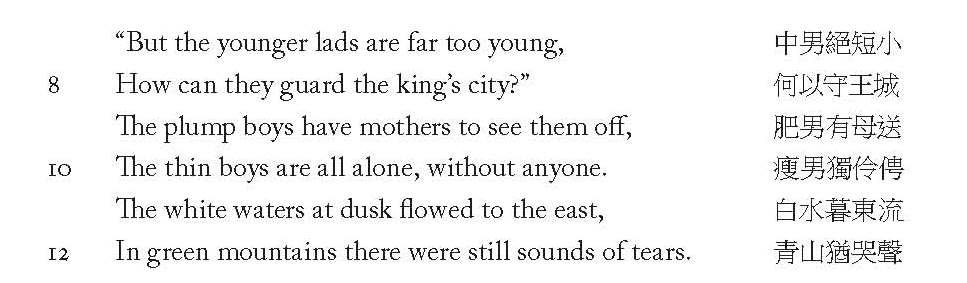

The poet’s initial question conveys his surprise that the officer is conscripting mere youths, and in reply, the officer dully repeats the orders that he is carrying out. Du Fu’s next question is addressed to the officer and yet it also provides an apostrophic transition from the scene of the encounter to the ruminative lines that follow:

Even though the conscription is community-wide, Du Fu perceives an inequality that exists between the relatively privileged and the impoverished: the “plump boys” still have their mothers, while the “thin boys” have no one left to them at all. Missing for all of the youths, of course, are the fathers, who have already gone to war, never to return. From this scene, the poet’s eyes follows the waters’ flow, out toward the east, and yet he still cannot escape the misery of separation, the sounds of crying following him even as he turns away. Drawn back into the scene, Du Fu now addresses all of the wailing mothers and sons, as a community that is united in its grief:

There is no comfort that he can give the conscripts and their mothers; for Du Fu, the purpose of poetry is not to assuage their grief but simply to bear witness to their suffering. In any case, what can he say that would make a difference? The universe itself is uncaring, without feeling, and the poetic imagination can do nothing to change this.

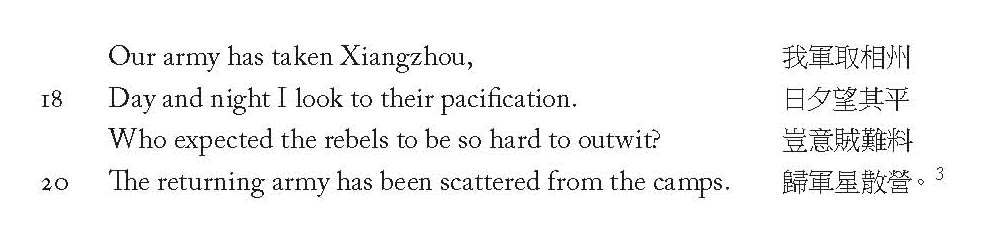

Du Fu turns away again, this time to comment on the historical situation that has impelled this conscription. He writes:

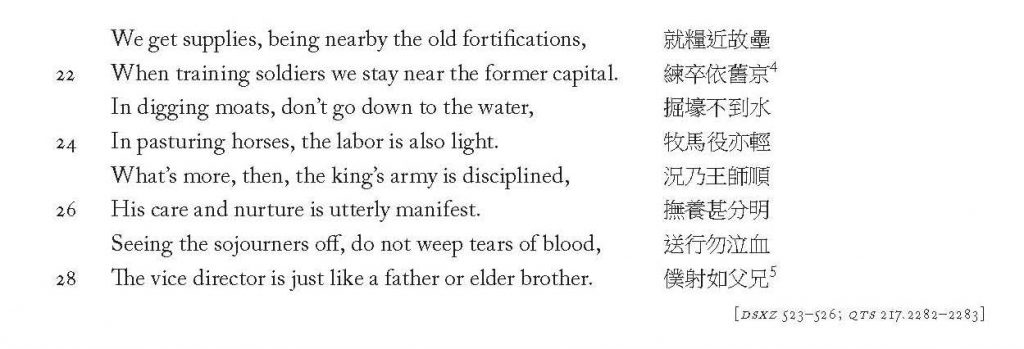

Here we find reference to the battle at Yecheng (referred to by the name of Xiangzhou). Although Guo Ziyi may have “taken” Yecheng, laying siege to An Qingxu, he would not succeed in its pacification. Du Fu softens the description of the Tang armies’ defeat, referring to them as the “returning army,” though it is clear that the rebels have “scattered” them “from the camps.” Thinking on this recent setback, Du Fu attempts to provide a small measure of comfort to the conscripts, telling them that life in the army will not be that bad. He writes:

It is not clear whether Du Fu truly means what he says, or whether he believes it. Perhaps, in the face of wailing women and boys, he finds that he must speak a comforting falsehood to give some hope to those who would otherwise “weep tears of blood” in their despair. Whereas he earlier had proclaimed the heartlessness of heaven and earth, here he attempts to convince his audience that the emperor truly cares, that Vice Director Guo Ziyi is like a father or an elder brother. The bitter truth, of course, is that the emperor does not know the sufferings of these mothers and boys and that the conscripts’ true fathers and elder brothers are likely dead, killed in the rout that was the battle at Yecheng. Though Guo Ziyi might yet lead the troops to victory, he is but a poor substitute for their loss.

The poem “The Officer at Shihao” (“Shihao li”), the third of the “Officers” poems, shares with the first poem the common theme of conscription. In this last poem, Du Fu describes officers coming into the village of Shihao to round up any able-bodied person still available.6 He sees an old man escape by leaping over a wall and then witnesses the old man’s wife pleading with the angry officer. This monologue takes up most of the poem:

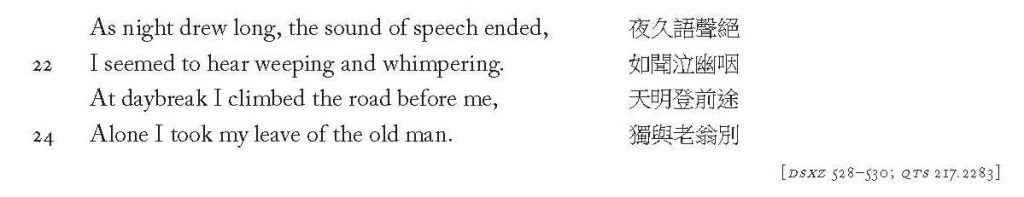

To this plea, there is no response, though the officer seems to grant the old woman her request. The poem ends with a bleak scene:

It would appear that the old woman has left with the officer, saving her husband from certain death, though he now has no one left in the village to care for him, or to care for. The poet offers no words of comfort now, nor has he any advice to give to the old man who remains by himself in the desolate village. When the exigencies of war impel the government to take both the young and the old to fight its wars, there is no restitution that poetry can provide. All the poet can do is to bear witness to the old couple’s powerlessness, as well as his own impotence in the face of such suffering.