China Trans Formed

“After Eunuchs deftly explores how the introduction of Western biomedicine transformed understandings of gender, sexuality, and the body in Chinese contexts from the twentieth century onward.”

~Ari Heinrich, University of California, San Diego

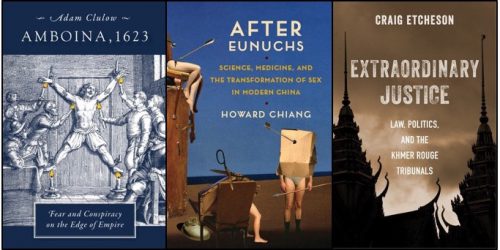

Today we are happy to bring you a guest post by Howard Chiang, author of the newly published work, After Eunuchs: Science, Medicine, and the Transformation of Sex in Modern China. In this book, Chiang traces the genealogy of sexual knowledge in China from the demise of eunuchism to the emergence of transsexuality, showing its role in the formation of Chinese modernity. Theoretically sophisticated and far-reaching, After Eunuchs is an innovative contribution to the history and philosophy of science and queer and Sinophone studies.

Remember to enter our drawing for a chance to win a copy of this book!

• • • • • •

In the twenty-first century, we have witnessed two astonishing developments. The first is China’s growing strength as a global (economic) superpower. The second is the worldwide political movement for queer and transgender rights. On the surface, they do not seem to be directly related to one another. While these developments may have surprised some people, both have more so confirmed the anticipation of others.

In the case of China’s recent rise, some economic historians (e.g., Andre Gunder Frank) have argued that the century of humiliation since the Opium Wars was merely a blip in China’s long history. The “Middle Kingdom,” and East Asia more broadly, has moved toward recovering its traditional dominance in world economy in the last few decades. With respect to queer and transgender recognition, many activists and scholars alike have considered it a logical extension of the gay and lesbian movement born in the 1960s and 1970s. Around the turn of the new millennium, it seemed inevitable for queer- and transgender-identified people to question the limits of binary thinking and to advocate for a more fluid conceptualization of gender and sexuality. These efforts in rethinking, of course, have had a wider bearing on the life of straight and cisgender individuals as well.

For over a decade, I had sought ways to make sense of these two historical developments and translate them into a synthetic narrative. The result of that effort culminated in the publication of After Eunuchs: Science, Medicine, and the Transformation of Sex in Modern China. In fact, I discovered that Chinese people did not wait till the end of the twentieth century to talk about sex change. My story begins with the ending of a historical epoch: the demise of castration. Toward the waning decades of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), China’s reputation as a weak and lacking polity reciprocated the global perception of Chinese eunuchs—castrated male servants of the emperor—as “diseased” and backward subjects. The late nineteenth century, moreover, witnessed the first explosion of visual, oral, and archival records documenting the details of castration. By turning the eunuch’s body inside-out, the circulation of these ideas about Chinese castration decisively feminized male eunuchs—and thereby subordinating China’s global image.

A hand-drawn image of a Peking eunuch produced by a French doctor. Source: Richard Millant, Les Eunuches à travers les ages (Paris: Vigot, 1908), p. 234.

My narrative ends with the social origins of a new era: the media reports of the alleged “first” Chinese transsexual, Xie Jianshun, in Cold War Taiwan. When Xie first commanded widespread media attention, journalists often called her the “Chinese Christine.” With this label, they were referring to the American transsexual celebrity, Christine Jorgensen, who glamorized the pursuit of sex reassignment and became a worldwide household name in the 1950s. After Xie’s story made headlines, Taiwanese newspapers began to report in an unprecedented rate stories of gender variance and non-conformity. The subject of sex transformation suddenly moved to the center of national spotlight in Taiwan.

The success of Xie Jianshun’s sex transformation. Source: Zhongyang ribao [Central daily news], September 9, 1955.

Yet as After Eunuchs shows, the path from the demise of eunuchs in imperial Peking to the emergence of transsexuality in post-World War II Taiwan was anything but straightforward. This trajectory interweaved several significant developments in the first half of the twentieth century: the consolidation of a biomedical concept of sex and the naturalization of the human body; the introduction of an empirical style of reasoning about sexuality; the emergence of a scientific theory that places everyone somewhere on a continuum between absolute maleness and femaleness; and the way anomalous bodies (e.g., eunuchs and hermaphrodites) served as a conceptual anchor for people to grasp new and foreign ideas about sex mutability. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, the Chinese press reported on cases of male-to-female and female-to-male transformations from both within domestic contexts and abroad.

Yao Jinping’s female-to-male transformation. Source: Shen Bao [Shanghai news], March 17, 1935.

The story of Lili Elbe (also known as the “Danish Girl”) reported in China. Source: Chen Yucang, Shenghuo yu shengli [Life and physiology] (Shanghai: Zhengzhong shuju, 1937), p. 246.

Ultimately the book shows that alongside the changing conceptualizations of “sex,” the very idea of “China” had also evolved over the course of the twentieth century. Pivotal to this parallel transformation was the making of “two Chinas”: the People’s Republic of China ruled by the Communist Party on the mainland and the Republic of China governed by the Nationalist Party in Taiwan. My study shows why debates over gender and sexual identity offer a luminating lens into larger concerns over political and national sovereignty. The rise of China and the growing queer/transgender visibility, then, can no longer be conceived as independent of one another, but are intimately connected in the history now documented in After Eunuchs.

• • • • • •