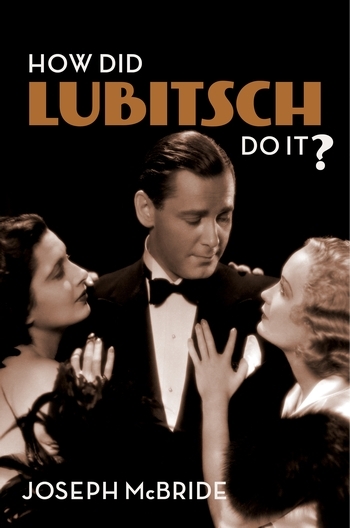

Is Lubitsch’s a “Lost Art”?

This week, our featured book is How Did Lubitsch Do It?, by Joseph McBride. Today, we are happy to present an excerpt from the book’s introduction.

Enter our book giveaway by 1 PM today for a chance to win a free copy!

• • • • • •

Although generally regarded as a comedy director, Ernst Lubitsch could blend comedy and drama with seeming effortlessness. He displayed that gift, for instance, in filming Oscar Wilde’s classic play Lady Windermere’s Fan as a silent film that finds greater emotional depths beneath Wilde’s brittle epigrams (not one is used as an intertitle). And his romances and musicals were able to pivot with breathtaking gracefulness from farce to feeling. That skill is epitomized when Jeanette MacDonald’s title character in The Merry Widow, pretending to be the kind of Parisian prostitute fancied by Maurice Chevalier’s Count Danilo, expresses her deeper sensibilities by waltzing pensively around him in Lubitsch’s most dazzling tracking shot. In To Be or Not to Be, Lubitsch executes his own most daring and sustained directorial pirouettes from comedy to historical tragedy, which aroused the acute discomfort and disapproval of some of its contemporary observers but amazed admiration from audiences today.

The cigar-chomping, slyly grinning Lubitsch could be scathing in his satire, although he usually favored a rapier and not a pistol as his weapon of choice. Though Lubitsch’s films help define romanticism in cinema, his is always tinctured with a bittersweet dose of irony. His disciple Billy Wilder was more caustic than Lubitsch and has been both celebrated and flayed for his supposed “cynicism” and “misanthropy,” but he had his own broad streak of romanticism, a tendency that, however submerged earlier, came out of the closet in his later work, while other filmmakers were reveling in shock, crudity, and brutality. Wilder’s longtime writing collaborator I. A. L. Diamond more precisely defined his partner’s approach and with it the cultural affinity Wilder shares with Lubitsch: “It’s an old Viennese tradition that comes down from [playwright Arthur] Schnitzler. It is a Middle European attitude, a combination of cynicism and romanticism. The cynicism is sort of disappointed romanticism at heart — someone [critic Andrew Sarris] once described it as whipped cream that’s gotten slightly curdled.”

Lubitsch’s films, with their “Middle European attitude,” do show an unusual and generous tolerance for human foibles, stemming from a worldly lack of surprise over such failings. That is one of his major strengths. Especially in such a puritanical country as the United States, both Lubitsch and Wilder are often chastised for their frankly unsentimental attitudes toward human nature, especially where sexual relations between men and women are concerned. Their satirical viewpoints are sometimes reductively labeled as cynicism and treated as if they are detached from human feelings. One perhaps inadvertent by-product of this problem is a strange lack of warmth and humor in much of the critical writing about Lubitsch. Although some of the books about him are illuminating about his style and themes, they tend to focus more on formal or intellectual aspects of his work than on the basic stuff that makes them play so well with audiences: laughter and emotion.

Lubitsch’s reputation today rests largely on his comedies. It is hard to argue that his German historical spectacles, for all their considerable merits, have as much lasting importance or artistic originality as the comedies, whether German comedies, which seem fresher and more original to modern eyes, or his Hollywood classics. For Lubitsch, in both kinds of films, politics is seen through the prism of human behavior rather than the other way around. Critics argue about the value of seeing history through a partly comic vantage point, as Lubitsch does; that argument is partly a matter of taste and sensibility. Some of those charges are overwrought and overly doctrinaire, but some are on the mark in analyzing the films’ limitations. Lubitsch’s German comedies, in their more modest goals of providing zany entertainment, hold up much better today than the historical spectacles, which were seen as more impressive at the time because of their subject matter and scale of production.

From today’s perspective, it can be seen that Lubitsch’s formative work in Germany in both kinds of filmmaking made him as important a figure in the artistically fertile postwar Weimar Cinema as Fritz Lang and F. W. Murnau even if they generally received more favorable reviews in that period. Those directors, who also went to Hollywood (with less sustained success than Lubitsch), have tended to be more highly regarded by film critics and historians ever since because they consistently worked in a more obviously “serious” and “respectable” vein. However, despite Lang’s often-stunning pictorial values, his ponderous style and lack of humor make much of his output heavy going today; Murnau’s body of work, just as powerful stylistically, has more variety and flair, more sense of poetry. But neither attempts the kind of witty and incisive social commentary that Lubitsch staked out as his personal domain. The humorous and bawdy aspects of Lubitsch’s historical spectacles make them more watchable today than most of the spectacles made by Hollywood filmmakers of the time who were still under the spell of Victorianism.

Dismissing Lubitsch as merely licentious or frivolous in his satire of sexuality and the human weaknesses of royalty and aristocracy is to miss the point that his work is “only superficially superficial,” as Noël Coward said in defense of his own plays. This censorious approach to Lubitsch, among other limitations, ignores the emotional and moral dimensions of his views on social relations. But these questions are complex, not to be dismissed lightly, and they deserve full and searching exploration in this book.

In a 1967 tribute to Lubitsch for the Directors Guild of America magazine, Billy Wilder wrote, “Oh, if we were lucky, we sometimes managed a few feet of film here and there in our work that momentarily sparkled like Lubitsch. Like Lubitsch, not real Lubitsch.

“His art is lost. That most elegant of screen magicians took his secret with him.”

But is it lost, irrevocably? That is one of the questions How Did Lubitsch Do It? will explore. It is a question of greater urgency as mainstream American filmmaking sinks into the mire of frenetic hit-’em-over-the-head sensationalism and coarse anti-humanism and as it gets farther from the kind of humane, subtle, sophisticated values Lubitsch’s films embody. A greater celebration of his work may not restore him to the centrality he deserves to occupy in our film culture, but perhaps it can repair some of the cultural damage.

A seriocomic romantic exchange in Lubitsch’s greatest film, Trouble in Paradise, best reveals the profundity beneath his lighthearted surface. In this romantic comedy involving a love triangle, Herbert Marshall’s suave jewel thief, Gaston Monescu, is the partner of a pickpocket, Lily (Miriam Hopkins), but he has been conducting a serious flirtation with a wealthy woman, Mariette Colet (Kay Francis), whom they have come to rob. Eventually Gaston falls in love with Mariette, a conflict that makes him doubt his mission and feel guilty over his deception of both women, but when his criminal activities catch up with him, he has to abandon Mariette and escape with Lily. Lubitsch exquisitely balances our sympathies among all three characters; rather than loading the dice toward one woman or the other as movies usually do, he makes it as hard for us to choose between Mariette and Lily as it is for Gaston. Finally, as Gaston is leaving, he ruefully, if presumptuously, asks Madame Colet, “Do you know what you’re missing?” Even though by now she is now fully aware of his deceit, she closes her eyes and nods, evidently thinking of romantic bliss. Then Lubitsch springs one of his most delicious ironic twists. “No,” says Gaston, pulling out a strand of pearls he has stolen from Mariette as a consolation prize for his (regular) mistress. “That’s what you’re missing. Your gift to her.” Displaying infinite grace, Mariette tells him, “With the compliments of Colet — and Company.” This most moving scene in Lubitsch’s work is a consummate example of his mingling of romance and regret, tenderness and pain. It is an exchange that shows how he could evoke the complex interplay of seriocomic human emotions better than almost any other director.

There is nothing on that level of subtlety or grace in American films today. Much of what passes for American film entertainment today would benefit greatly from a fresh infusion of the sparkling Lubitsch tradition of cinematic wit and intelligence. By examining the gifts Lubitsch has given to our culture, even if much of his legacy has been lost, misplaced, and forgotten, I hope to show exactly what it is that we are missing in shortsightedly shunting aside his salutary influence. So it is not with despair but with quixotic hope that in this book I find how that missing spirit might not be lost after all, and how it might again be felt in our filmmaking, or at least in our film viewing.