Capturing the tone in the translation of City Folk and Country Folk

Enter the City Folk and Country Folk Book Giveaway here

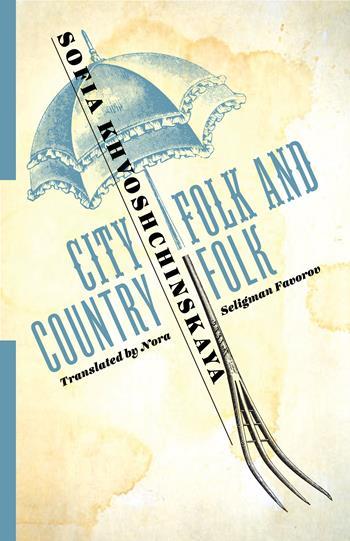

Welcome to the Columbia University Press blog! This week we are featuring Sofia Khvoshchinskaya’s City Folk and Country Folk, which has recently come out in the Russian Library series. Today Elaine Wilson, a PhD candidate in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Columbia University, explores some of the decisions Nora Seligman Favorov made in translating the book.

As a fledgling translator, examining the work of other, more experienced translators is consistently an informative and reflective exercise for me. Translating a work of literature is more complex than simple transmission of meaning across language, for a story is more than the sum of its parts. Often there are cultural and political stakes in the game, factors not easily separated and compartmentalized thanks to the curious way in which words and their arrangement bear the weight of multiple and varied ideas. Sofia Khvoshchinskaya’s novel, City Folk and Country Folk, is one such work that contains multitudes: It is a feminist novel, a satirical piece, a reflection on social change in nineteenth-century Russia, and, an entertaining read to boot. Nora Seligman Favorov is the first translator to deliver this literary gem to the English-speaking world, and she has done so with a keen ear for her Anglophone audience.

The beginning of a book sets the tone for the rest of the story. Any translator will tell you that the initial pages are crucial, that these early paragraphs introduce and establish both a sense of the author’s style from the original text and the translator’s stylistic sensibilities within the translation language. In City Folk and Country Folk, one of the first things a reader will notice is the narrative voice. At turns loving and sardonic, the third person omniscient narrator of Khvoshchinskaya’s novel tells the story using language that hints at familiarity. In the original Russian, the tone even feels conversational at times—Khvoshchinskaya practically concludes her opening paragraph with the colloquial “И что же?”, a Russian expression whose meaning, depending on context and intonation, can range from “so what?” to “big whoop” and “can you imagine?” This narrative style guides the audience with omniscient authority, but the tone conveys a figurative wink and a nod, the suggestion that the reader, like the narrator, gets it. Khvoshchinskaya employs the first person plural possessive “наш” (our)—a staple more of Russian speech than prose—to qualify the countryside, the climate, the food, and it ultimately invites the reader to consider these things from an internal perspective. The economic troubles of the day, the laughable habits and opinions of certain characters—these are presented to the reader as they might be to a friend or, perhaps fellow conspirator, and this implicit understanding between reader and narrator is what gives the novel so much of its charm.

Favorov’s English rendering of the opening pages of City Folk and Country Folk demonstrates her sensitivity both to Khvoshchinskaya’s Russian style and conventions of English writing. She maintains the inclusive “our” to bring the English reader into a sense of communion with the narrator, but she adjusts the colloquial quality in search of a more traditional English literary style. Nastasya Ivanovna, a landowner, country resident, and the leading heroine to whom we are first introduced, prefers traditional Russian ceramics and mushrooms to their more fashionable, Western European counterparts. By the social standards of her day, such tastes are “unrefined,” but Nastasya Ivanovna is only somewhat conflicted about this.

“Грубых вкусов своих она не выражала при всех, но зато с людьми, которые были ей по душе, смиренная и откровенная, она каялась в этих грехах своих. Она сознавалась сама, без чужих понуждений; не ясно ли отсюда, что она была способна совершенствоваться?”

[“She did not admit her unsophisticated tastes to just anyone, but, humble and frank, in the presence of people with whom she felt at ease, she repented these sins. Nobody forced her—she confessed them freely. Surely this suggests she was capable of self-improvement,” (Khvoshchinskaya, 4).]

The final line of this excerpt, the matter of improving oneself, is posed as a question in the Russian original: “не ясно ли отсюда, что она была способна совершенствоваться?” In the form of a question, the issue is framed in doubt, but it is unclear on whose part. If Nastasya Ivanovna’s, the question implies self-examination, a bit of desperation in the face of her failings before society; if the narrator’s, it reads more as an inference into Nastasya Ivanovna’s constitution. Favorov’s English translation does away with the question entirely, rendering Nastasya Ivanovna’s self-awareness as a rather definitive aspect of her character: “Nobody forced her—she confessed them freely. Surely this suggests she was capable of self-improvement.”

The switch from interrogative to declarative is a conscious move on the translator’s part, one whose intent I understand to be a departure from the more personal, dialectic quality of nineteenth-century Russian literature. (If you’re hungry for examples, see War and Peace.) With the declarative, Favorov’s prose shifts towards the English literary style. And while the frequent comparison may be tired, it is valid—City Folk and Country Folk is reminiscent of the works of Jane Austen, and Favorov’s choice in this instance seems to embrace the comparison. Treatment of Nastasya Ivanovna’s dilemma with a statement through free indirect discourse lends the translation the kind of third person narrative authority with which Austen presents the opinions of her British characters. As a result, some of the underlying anxiety Nastasya Ivanovna feels with respect to her own potential for “refinement” in the Russian text falls away, but what the translation gains is greater Englishness.

Favorov’s careful attempts to honor Russian and English stylistic norms operate at the word level, too. In the very first paragraph, the reader learns that Nastasya Ivanovna qualifies everything that happened that fateful summer using the word “напасть.” This word can be translated in English in various ways; its meanings including “tribulation,” “bad luck,” and “disaster.” But “напасть” also contains implications of action and transitivity. It suggests assault or attack. Favorov renders this word as “calamity,” a choice that initially seemed odd. For me, “calamity” carries connotations of natural disasters, but it also calls to mind ironic, almost cartoonish imagery (i.e., “Calamity Jane” or dialogue in Looney Tunes set in the Wild West). The latter implication stems from the rarity of this word in modern spoken English. It feels hyperbolic, old-fashioned. But given these considerations, “calamity” is in fact a rather apt translation. It works to convey an old-timey feel and the meaning of an onslaught of misfortunes. Nastasya Ivanovna considers the events of the story to have happened to her, events that were out of her control. Khvoshchinskaya’s Russian text implies this with the word “напасть” and a character named Nastasya, as they appear together in the old Russian saying “Пошла Настя по напастям,” a version of “when it rains it pours.” For Nastasya Ivanovna, there was no calculated attack on her peaceful country life, but rather these events were fated. Favorov’s English underscores Nastasya Ivanovna’s exaggerated perception of the events as a string of disasters imposed upon her: “It is… a shame that fate did not earlier, before the events of last summer, send Nastasya Ivanovna someone who could have prepared her for these events, who could have warned her, for instance, that proclaiming a fight for one’s convictions to be a disaster and a punishment from God is far more shameful than blurting out a preference for local mushrooms over truffles” (Khvoshchinskaya, 4).* These words are, of course, dripping with irony, throwing the intended meaning of “напасть” against a backdrop of absurdity, and this shows the choice of “calamity” in a favorable light: its semantic shades bridge the gap between expressions of misfortune and the nonsense of the circumstances.

Favorov’s translation is full of potential for this kind of analysis, but the opening moments of City Folk and Country Folk demonstrate Khvoshchinskaya’s style. Her comic and astute observations illustrate and poke fun at her nineteenth-century reality, and so landing the narrative voice in the English is key. Our introduction to Nastasya Ivanovna, with her simple tastes and her bouts of anxiety, sets the stage for the story to follow, but it is also a proving ground for style. These early pages show Favorov’s thoughtful work; her translation captures Khvoshchinskaya’s wit and wisdom. And though reflective of traditional English literary conventions, in her translation the novel’s charm—its Russianness—shines.

*After writing this piece, I learned that Favorov finally decided upon “calamity” after consulting English translations of the Bible. A brilliant insight into her problem-solving process, this fact also bolsters what Nastasya Ivanovna wishes to convey, that she was subject to greater forces.