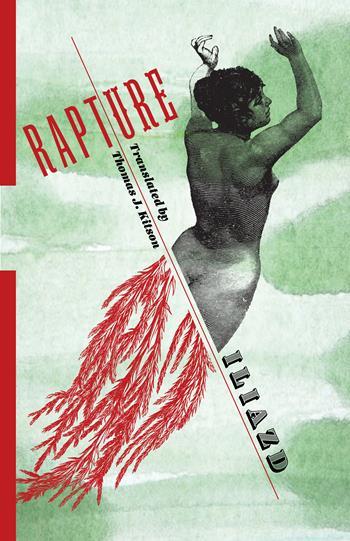

Interview with Thomas J. Kitson, translator of Iliazd's Rapture

Iliazd’s Rapture is the newest title in the Russian Library, a series that seeks to demonstrate the breadth, variety, and global importance of the Russian literary tradition to English-language readership through new and revised translations of premodern, modern, and contemporary Russian literature.

Thomas J. Kitson will be speaking about Rapture with Jennifer Wilson on Thursday, May 4th at 5:00 PM at NYU’s Jordan Center. More information here

Enter the Rapture Book Giveaway here

Today Veniamin Gushchin, CC ’18, Russian Library Intern interviews Thomas J. Kitson about his translation of Rapture by Iliazd

What makes Rapture a classic of literary modernism, worthy of being read alongside the works of James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and others? Why has it been ignored for so long?

I’ll take your second question first. Rapture got off to a bad start in the politically touchy and rapidly shifting Russian publishing milieu of the late 1920s, both in the Soviet Union and in the Emigration. But Iliazd took a stance that tended to undermine his own cause – and eventually, this became a fully conscious campaign to create art that would “vanish idly,” like the storied hidden treasures in the novel. When Iliazd began writing his novel in 1926, there was every indication Soviet publishers wanted to establish ties with left-leaning émigré writers. Iliazd sent the first chapters to his brother Kirill in the USSR, expecting it would appear alongside works by “fellow travelers” like Isaac Babel, Boris Pilnyak and other authors who had been moving more or less fluidly between Moscow, Berlin, and Paris. Kirill submitted the manuscript just when those publishing opportunities started disappearing. A new “proletarian” campaign in literature, not just against fellow travelers and their favored journal, Red Virgin Soil, but also against the avant-garde gathered around the journal LEF, including Vladimir Mayakovsky, coincided with Stalin’s consolidation of power within the Party. Iliazd’s manuscript was rejected on a combination of aesthetic and ideological grounds (reads like it’s been translated, “clumsy,” even “illiterate”; opens with a monk, displays “aesthetico-contemplative indifference to characters” and entertains a “mystical state of the spirit”). Iliazd wrote an exaggeratedly tendentious, almost mocking rejoinder to the Soviet editors emphasizing his “internationalism” and asserting that he’d been in the crowd that greeted Lenin at Finland Station in April 1917. But under conditions in the Soviet Union in 1928, his avant-garde pedigree and émigré status made him profoundly suspect. To my knowledge, his contacts in the USSR never made another attempt to publish the novel, although copies of it circulated among a small group of admirers in the 1930s. So for the vast majority of Russian readers, the novel never existed at all.

In Paris, Iliazd had taken a resolute stance against the anti-Soviet émigré arbiters of culture who controlled access to the Russian-language press, and there simply wasn’t a sufficiently large Russian-speaking audience independent of those organs. Iliazd’s associates, like the Dada writer and painter Sergei Charchoune and the younger poet Boris Poplavsky, had, one by one, “compromised” for the sake of being able to publish. Again, as far as I know, Iliazd never made any overture at all to the main Russian-language publishers, and even preferred unrealized schemes to translate the novel into French. He gave away a large number of the 750 copies he published at his own expense in 1930, and Russian bookstores refused to carry what was left on the pretext that it included several obscenities. Iliazd’s marketing strategy was openly challenging to potential buyers: “If you’re that inhibited, don’t read it!” So it disappeared there, too.

When Iliazd later gained a reputation in France as a printer and publisher of artists’ books, Rapture didn’t have the visual appeal to overcome its inaccessibility to non-Russian readers. It’s an indication of how thoroughly forgotten the novel was that it didn’t have champions to publish it during the Glasnost explosion. Luckily, there have been connoisseurs over the last thirty years, in and outside Russia, to keep pushing it forward in small editions. I find myself thinking that this is probably the most high-profile publication the novel has ever had, and that puts a lot of responsibility on me.

The novel’s modernism lies primarily in its post-Great War, post-Christian exploration of human desire for transcendence. Humans are thoroughly unnatural, time-bound, dying animals whose relentless artifice inevitably creates nostalgia for Nature, or the Infinite, or Unchanging Eternity, or Ideal Beauty, and efforts to “recover” these unattainable states exact a certain quantity of violence of one kind or another. Beneath his entertaining adventure story, Iliazd introduces Freudian drives, linguistic minimal phonetic pairs, Nietzschean jenseits, chivalric quests and fairy-tale tasks, mythologies of metamorphosis, including Christian Transfiguration and Resurrection, Romantic and Symbolist longing for the Eternal Feminine, and various strains of apocalypticism, among other features, to generate layers of meaning. Iliazd considered his novel above all a “commentary on… poetry as an always vain endeavor.” It is full of allusion, but also poetically structured (circularly, like many other modernist works) with rhyme, inversion, and recapitulation. And it wears all this remarkably lightly.

What new insights about the competing literary movements at the beginning of the twentieth century can be gained from Rapture?

Laurence, the protagonist, is said to be a portrait of Vladimir Mayakovsky, and the bare storyline grows out of a transparent pre-war polemic in which Zdanevich (not yet known as Iliazd) described a film scenario called “The Fallen Man,” a melodrama about a promising young revolutionary’s utter degradation and dishonorable death. While Iliazd could still be intransigent, I think what he saw during the war took away his unforgiving polemic edge, and Rapture is suffused with sympathy and self-deprecation – all poets are necessarily failures. We know that when Futurist and Acmeist poets rejected their Symbolist fathers, they retained, as with any Oedipal response, many of their fathers’ techniques and attitudes. The French scholar Régis Gayraud is absolutely right to see in Rapture “a return to a species of Symbolism bearing the experience of the avant-garde.” I suspect there may be a much harsher inscription of Nikolai Gumilev, the Acmeist leader executed by the Bolsheviks, lurking in the novel, but that’s something I haven’t dealt with.

I also hope, since Iliazd was close to Paul Eluard and frequently attended Surrealist meetings where Freud, Gothic novels, and German Romanticism were among the topics, someone will put this novel in conversation with the Surrealist prose emerging at the same time, like Louis Aragon’s Paris Peasant and André Breton’s Nadja.

In translating Rapture, how did you navigate the multiple layers of cultural distance between the English-language reader and the text: first Russian, then Georgian?

Oddly, I didn’t feel that I needed to mediate much here. There’s an ongoing debate about where the novel is set (Soviet editors, to start with, didn’t like its lack of specified time and place). I lean toward agreeing with Elizabeth Beaujour that it’s simply set among mountain peoples, and there’s no need to specify more than Iliazd does. Iliazd loved the village culture of Georgia (and of the Anatolian areas he explored during a wartime archaeological expedition), but he also loved the Pyranees, and Petr Kazarnovskii makes a case for linking Rapture to the Albanian mountain settings that inspired Zdanevich’s first play. There are features that suggest a setting in the Russian Empire, but, once again, I don’t feel compelled to set that down in stone, and, in fact, I think the novel gains, especially on the mythical and fairy-tale levels, by leaving the question open. I deliberately translate vodka as “brandy” just for that reason. There’s a lovely interplay between the openness of “Once upon a time, in a kingdom far, far away” and maddeningly detailed descriptions of seemingly fantastic ethnographic practices and beliefs that turn out to be lifted almost verbatim from Iliazd’s notes about specific villages he visited. I want English-language readers to be immersed in minute detail when Iliazd decides to give it without breaking the effect of fantasy – and the same holds for the urban settings with their commercial phantasmagoria and the Party’s revolutionary striving for “expedient coercion.”

Rapture is rich in literary and historical references, especially to the Russia literary scene at the turn of the century. For English-language readers with little to no knowledge of the Russian literary tradition, do you believe this text is truly accessible? To what extent?

I think the novel can be enjoyed without being able to catch all the allusions (I certainly haven’t). Many English-language readers are familiar with Dostoevsky and will certainly find that characters and situations from his major novels come to mind. Readers who know modern French poetry will find echoes of Baudelaire and Rimbaud (for instance, the monk Mocius sees a satyr gnawing a rifle barrel). I have incorporated some vocabulary and phrasing from the King James Version of the Bible, which I hope will sound in many English-language readers’ ears. Some allusions, like Laurence’s invocation of Boris Pasternak when he vows to wed the government’s soldiers to “our sister death,” are extremely fleeting, but will probably register with some readers. I think the book will reward any level of reading experience for curious, intelligent readers.

When I’m feeling very inadequate as a translator, I imagine Rapture could warrant something like Yale University Press’s simultaneous publication of two versions of Máirtín ´O Cadhain’s Cré na Cille (The Dirty Dust and Graveyard Clay), where the alternate version would focus sharply on another level of puns and allusions that results in an entirely different book.

Translators generally fall along a spectrum regarding how faithfully they believe a translation should adhere to a source text. Where do you fall on this spectrum of remaining to true to the text and making it accessible to the reader?

I don’t think of remaining true and making it accessible as mutually exclusive tasks. I think the text can have some odd features and still be accessible, especially because I imagine a reader with a generous tolerance for what’s unfamiliar. In part, remaining true to this text meant taking into account the specific kinds of incomprehension or bewilderment evident in the fragmentary accounts of the manuscript’s effect on its first readers. I was particularly drawn to the impression that the novel had been translated from another language into Russian. How should I handle that in my own, actual translation? I retained a few syntactic and punctuation features I thought might create just a slight edge of unease. They were flagged at the proofreading stage, so they were perceptible, but we agreed that they didn’t impede reading. But my sense of hitting the right balance depends on the text. If I were tackling Zdanevich’s beyonsense plays, I’d have a very different feeling for what I want readers to have access to.

What are your hopes for this publication? Do you have any particular expectations for its reception or impact both on academia and general readership?

As I mentioned above, I feel like this translation has the potential to introduce Rapture to readers on a scale it’s never achieved. Today, the sheer fact of making it available in English already provides a huge advantage. I fantasize that bilingual Russian speakers will encounter it and want to read Iliazd’s Russian.

At the same time, I hope Rapture finds a place for general readers alongside Dostoevsky and Bulgakov, but also alongside Woolf and Lawrence and Mann. And, in a sense, I hope readers will think of it not as a Russian novel, but as an important element in a much broader literary heritage.

Are you interested in translating any of Iliazd’s other novels or works?

I’m currently translating Iliazd’s Philosophia, set in 1921 among Russian refugees in Istanbul — a psychologically and referentially paranoid novel moving toward a terrorist plot to blow up Hagia Sophia. It feels very timely.