With and After Orientalism — Carrie Preston

“After almost forty years of important and illuminating discussions of orientalism and ironic responses to the scourge of empire, I think a new space is opening for global or transnational scholarship and intercultural art. Participants in this space are not naïve about the continuing ramifications of empire … [b]ut they also want to move beyond irony and make room for pleasure, inspiration, even enchantment in the fraught encounters between cultures.”—Carrie Preston, author of Learning to Kneel

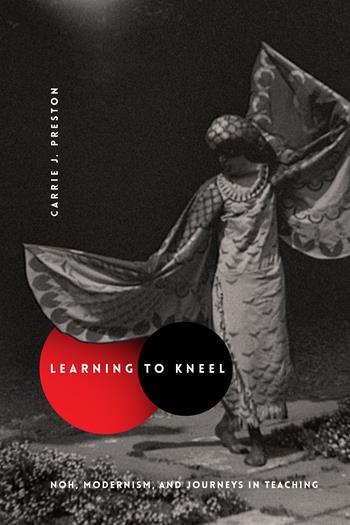

The following post is by Carrie Preston, author of Learning to Kneel: Noh, Modernism, and Journeys in Teaching:

A century ago, W. B. Yeats’s first noh-inspired play for dancers, At the Hawk’s Well, was performed in Lady Emerald Cunard’s London drawing room with an invited audience that included Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot—one time we know for certain that these three great modernist poets were all together in the same room.

Also in the room was Ito Michio, the Japanese-born performer who choreographed and danced the role of the Guardian of the Well and went on to have an important career in American modern dance.

(Ito Michio as the Guardian of the Well in At the Hawk’s Well (1916))

The French artist Edmund Dulac designed full wooden masks, made costumes, and composed and performed the music.

(Edmund Dulac with other musician and the cloth to be folded and unfolded at the beginning and end of each play for dancers.)

It was a fascinating collaboration and avant-garde modernist performance experiment. Eliot, also a great critic, claimed that Hawk’s Well made him think differently of Yeats, “… rather as a more eminent contemporary than as an elder from whom one could learn.” For him, Yeats soared into the new modernist generation with Hawk’s Well. Plenty of critical ink has been spent on Yeats in the past century, but this play has tended to be something of an exception and embarrassment, largely because it’s a pretty good example of orientalism, exoticism, and cultural appropriation.

There were many warnings against writing a book focused on Hawk’s Well and modernist noh, certainly against moving to Japan to take lessons in noh performance technique. I was literally becoming an orientalist, part of that academic tradition Edward Said famously defined in 1978 as being based on essential distinctions between the so-called “Orient” and “Occident.” The “Orient” (primarily the Middle East for Said) is imagined to be spiritual, passive, effeminate, exotic, traditional, and inscrutable, while “the Occident’” is rational, aggressive, masculine, central, modern, and knowable. Said argued that scholarly and aesthetic accounts of “the Orient” justified empire, even when, as with Yeats and noh, the artists were celebrating nonwestern achievements to counter white European cultural stagnation. In later works, Said clarified that he viewed modernism as an “ironic” rather than “oppositional” response to empire. And in the decades that followed, critics have recognized that cultural exchange is inevitable in modernity and can’t simply be deplored, but few models of transmission emerged that did not emphasize irony, mimicry, or appropriation. Warnings from Said and other postcolonial theorists have contributed to my feeling that I should have been more ironic, certainly less enthralled, as I took noh lessons and researched modernist noh.

Yet, studying and participating in collaborative intercultural exchange, however fraught and full of mistakes, tended to encourage my optimism rather than irony. Accusations of orientalism and appropriation begin from a desire for cultural sensitivity, but they can unintentionally reinforce the notion of an unbridgeable divide between east and west. Certainly we can identify plenty of orientalist assumptions in Yeats, Pound, Dulac, and their collaborators, including Ito, one of the most successful performers to build a career out of orientalist performance.

But, after almost forty years of important and illuminating discussions of orientalism and ironic responses to the scourge of empire, I think a new space is opening for global or transnational scholarship and intercultural art. Participants in this space are not naïve about the continuing ramifications of empire, the offense of cultural appropriations that look more like theft, and the ways that outdated polarities like east and west still encroach upon our thought. But they also want to move beyond irony and make room for pleasure, inspiration, even enchantment in the fraught encounters between cultures.

As part of a centenary celebration of At the Hawk’s Well, the Japan Society Gallery in New York will be hosting a fall exhibition called Simon Starling: At Twilight that reimagines the 1916 production of At the Hawks Well with a sort of triptych approach: Modernist masterworks associated with Yeats’s play are set beside new noh-inspired masks, costumes, and dance, as well as traditional noh masks from the plays in Pound’s first noh translations. I imagine Learning to Kneel as part of an effort to work across cultures and time periods while being wary of orientalism but also of the ways it can, like all vast critical rubrics, shut down conversations and collaborations and shut off sources of inspiration and enchantment.