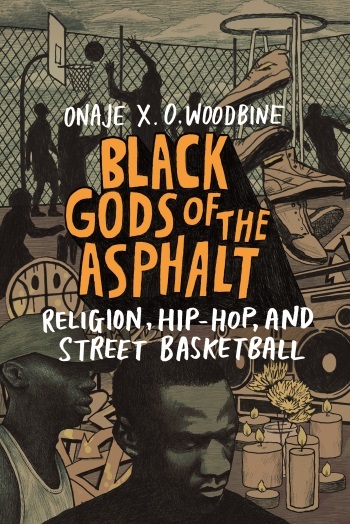

A Media Roundup for "Black Gods of the Asphalt"

“Black men’s bodies are overdetermined by racism and poverty on the court, but to stop there is to strip ballplayers of agency and to overlook their lived experiences of the games. In a twist of irony that rivals the sleight of hand of a crossover dribble, social scientists have attempted to explain black basketball by setting aside the subjective experiences the players have of it. In their desire to remain objective and to adhere to disciplinary boundaries, scholars have reduced basketball to a set of rules predetermined by external conditions.” — Onaje X. O. Woodbine

This week, our featured book is Black Gods of the Asphalt: Religion, Hip-Hop, and Street Basketball, by Onaje X. O. Woodbine. For our final post of the week, we’ve collected a number of the best articles and interviews on and with Onaje X. O. Woodbine looking at his new book.

First, at Killing the Buddha, read an excerpt on the 2013 Fathers Are Champions Too basketball tournament and other streetball tournaments from Black Gods of the Asphalt:

Black men’s bodies are overdetermined by racism and poverty on the court, but to stop there is to strip ballplayers of agency and to overlook their lived experiences of the games. In a twist of irony that rivals the sleight of hand of a crossover dribble, social scientists have attempted to explain black basketball by setting aside the subjective experiences the players have of it. In their desire to remain objective and to adhere to disciplinary boundaries, scholars have reduced basketball to a set of rules predetermined by external conditions. The powerful socioeconomic forces of poverty, racism, and masculine role constrain black male bodies, pushing them toward limited definitions of self as ballplayers, gangsters, and hustlers. This “symbolic violence,” as Bourdieu refers to it, is often embodied and internalized by the players. But to stop there is to leave us with only a thin sense for the human and lived dimensions of these games. The experience of the court as a vehicle of self-emancipation is stripped away. The living dimension of this urban religion is lost.

Woodbine was interviewed twice at WBUR, Boston’s NPR news station. First, listen to Woodbine discuss how his desire to tell the stories that come up in his book led him to take Black Gods of the Asphalt to the stage.

“It was storytelling,” Woodbine says. “This was inner-city, street-level storytelling. And I thought, ‘Why not actually, consciously, do this on the stage and create a conscious, ritual space in the theater? And so, I wrote a script with my father and my wife to try to tell these stories in a way that can impact audience beyond the streets.”

In his second interview, Woodbine delves into his decision to leave the Yale basketball team, and runs through his story of the experiences that led him to write Black Gods of the Asphalt.

At NewsOne, Woodbine discussed “the interesting connection between hoops and African-American inner-city culture” with host Roland Martin:

What I found in my interviews and observations was that Black men were going to the court really after somebody had died or been stabbed or shot, and they would experience the presence of this person on the court and it became sort of this ritual space where they could grieve, where they could put the thought of the streets in abeyance for a moment and experience some form of transcendence.

In the Boston Globe, James Sullivan wrote a great profile of Woodbine:

It took years for Woodbine to get over what he calls his “survivor’s guilt” — being the one who found his way out of the neighborhood. Many never had the chance.

“When I’d go back, I would feel anxiety,” he said. “My heart rate would go up — I’d remember the trauma I’d experienced. I never was injured, but I saw people injured and was very close to it.”

Now, though, he thinks of himself as a bridge between cultures. At BU, one teacher posed a question that has stuck with him: When you think of the word religion, what comes to mind?

“I couldn’t help but think that the most sacred place I had been was on the basketball court,” he said.

Finally, on ESPN.com, Brendan C. Hall profiles the stage version of Black Gods of the Asphalt that Woodbine is putting up at Phillips Academy:

At one point in the play, one of the main characters, C.J., realizes he is a descendent of African women. That brings about a flashback, wherein the basket becomes a metaphor for the mind of God.

“There’s a line in traditional West Africa that says, ‘It’s a heavy load to carry death’s basket’, and what they are referring to is the ancestors,” Woodbine says. “There’s a form of good nature when you look into a basket and get messages from the ancestors, so the basket is a metaphor for memories.”