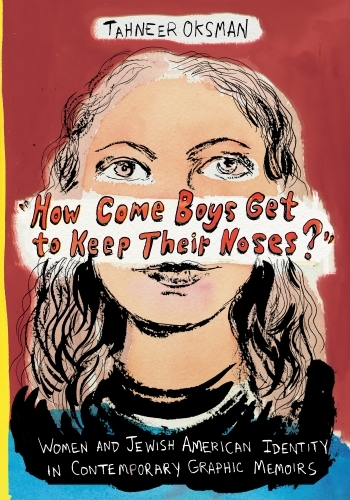

An Interview with Tahneer Oksman, author of "How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?"

“What’s interesting about comics is that you have artists drawing versions of themselves over and over on the same page. You can actually see their serial selves, their past, present, and future self-portraits in relation to one another.”—Tahneer Oksman

The following is an interview with Tahneer Oksman, author of “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?”” Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs:

Question: The graphic memoirists you write about in your book have complicated relationships to Jewish identity. What are some of the ways they express or articulate their ambivalence?

Tahneer Oksman: For someone like Aline Kominsky Crumb, her reflections on Jewish identity read, at least initially, like a general distaste for the Jewish Long Island community that she grew up in. Her memoir is saturated with visual and verbal stereotypes about Jews, and Jewish women in particular. But the more closely you examine her work, the more you recognize its complex push-pull: she incorporates those stereotypes in order to fully explore her own sense of self. In a way, she is continually mocking her own mockery.

Some of the other cartoonists I write about tend to be more overtly ambivalent. Vanessa Davis, for instance, expresses a clear adoration for various tenets of her Jewish identity, many of these associated with childhood and family. But within images portraying precious memories—of her Bat Mitzvah, for example—she incorporates words or body language that contradict the celebratory, engaged atmosphere depicted around her. Other artists, like Lauren Weinstein, express ambivalence indirectly, as when her young persona writes a letter to Mattel, complaining about how “All your Barbies look like Aryans!,” and then later laments her own so-called Jewish looks (including her nose).

Q: How does this differ from the ways in which Jewish male graphic artists might grapple with these questions in their own work?

TO: I don’t believe there’s any essential difference in the ways that Jewish women and men—or women and men more generally—portray identity in comics. In the book, I selected seven memoirists who, to my mind, successfully model this ambivalent Jewish identity that I set out to explore. There are plenty of other Jewish cartoonists who didn’t make it into the book, not because they don’t fit into this model but because I had to set limitations in order to effectively develop my ideas. The book is meant to introduce a way to start thinking about how identity functions in comics, and not as any kind of end point.

To my mind, crucial differences emerge when it comes to how different kinds of comics (and artistic and literary works more generally) are perceived. Certain subjects and styles are still considered amateur or frivolous both in and out of academic contexts. It’s still a very male-dominated medium in this way, no matter how many women skillfully assert themselves in various forms of print and online. This reception ultimately influences the ways that comics get made. In other words, there’s going to be an awareness, for artists and writers who have been marginalized, of certain critical tones, and that will inevitably find its way into the work, for better or worse.

Q: In what ways does the comics form allow for questions of identity to be expressed that distinguishes it from other forms?

TO: What’s interesting about comics is that you have artists drawing versions of themselves over and over on the same page. You can actually see their serial selves, their past, present, and future self-portraits in relation to one another. The layering that goes into this kind of storytelling—thought bubbles, verbal narrative, and various other visual cues—allows certain contradictions about identity to surface.

In a sense, what you’re looking at when you read autobiographical comics is the way a person sees herself, her history, the world around her. But since it’s a visual medium, and since all of us are always influenced by how others see us, you’re also witnessing the influence of others. When Kominsky Crumb draws her mother as a hideous monster, the reader experiences how stereotypes of Jewish women have shaped not only the artist’s view of her mother but also the artist’s view of herself.

Q: Do you have a favorite image from the book?

TO: There’s one image that I identify as a kind of centerpiece because it really gets at what I’m trying to say about what comics can show us about identity. The image is Lauren Weinstein’s 2008 drawing of a map, titled “The Best We Can Hope For.” Ironically, although I talk about the juxtaposition of images and words throughout the book, and although I focus all the while on what Scott McCloud refers to as “sequential art,” this image is a cartoon (a single frame) with no words incorporated into it. It tells the story of four central figures and offers not just a single depiction of any of them, but a series of portrayals unfolding all over the page. The map gets at some of the major points I address over the course of the book: diachronic and synchronic frameworks, the relational nature of identity, the power of scope and scale in establishing how we see ourselves and those around us. It’s a deep and imposing image.