Donald Trump and the Destruction of the American Century — Brian Edwards

In a recent article in Salon, They’ve destroyed us worldwide: Donald Trump, George W. Bush and the destruction of the American century, Brian Edwards, author of After the American Century: The Ends of U.S. Culture in the Middle East, examines what has happened to the more hopeful version of America that the country once exported. While acknowledging that the idea of “The American Century,” always had the ulterior motive to strengthen the United States militarily, economically, and politically, there was also a sense that American culture was infused with a sense of hope and innovation that could be taken up by others. Edwards writes, “The American century was built on a positive aura, not hate. From the romantic comedies of classic Hollywood to Coke’s ‘I’d like to teach the world to sing,’ America exported the promise of love.”

Even during the “American Century,” anti-Americanism, of course existed, but the recent events surrounding Donald Trump’s comments about Muslims coupled with recent U.S. policies have presented a very different portrait of the United Stated, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa. As Edwards suggests, “Trump’s bearing is all swagger, but he and his zealous supporters project a weak and defensive stance to the world. They have redefined the United States as hostile and fearful.”

Recent developments also represent a shift from the post-9/11 period Edwards explores in his book. In the wake of the terrorist attacks, many advocated for and implemented initiatives that resurrected the cultural cold war policies:

So, Hillary Clinton could be found championing the hip-hop initiatives that looked a lot like the jazz tours of a half-century earlier. In 2011, commenting on a state-sponsored trip of a hip-hop artist to Damascus, she said: ‘Hip-hop is America. . . . I think we have to use every tool at our disposal.’ As secretary of state, she was early to embrace what was called digital diplomacy, with young staffers leading the charge.

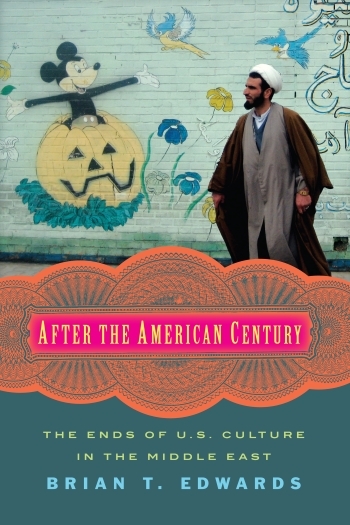

Over the past decade and a half, I have been charting the fate of American cultural products in the Middle East and North Africa, with extensive research in the region during a remarkable time. From Fez to Tehran, young Arabs and Iranians are intimately familiar with American popular culture. As I argue in my new book, After the American Century: The Ends of U.S. Culture in the Middle East, a newer generation across the Middle East and North Africa made a distinction between America as a creator of cultural products and the United States as a geopolitical entity. That meant that through the 1990s and 2000s, they could continue to enjoy and consume our attractive culture without contradicting their increasing dismay regarding our policies in their region.

As Edwards suggests, it is somewhat ironic that the Web, one of the greatest technological achievements by the United States in recent memory and one that has the potential for understanding and liberation has contributed and been the engine for spreading this more hostile version of America. Edwards concludes by writing:

Ironically, we have the greatest technological success of the American century to blame for the demise of the American century itself. Can we still harness the positive attitude of optimism, hope and ingenuity that represents the best of the previous era and restart a new relationship to the world based on respect, trust, and partnership?