Evan Ratliff on the Best American Magazine Writing of 2015

“Great writers will keep finding the wherewithal to chase the bold ideas, and great editors will keep finding ways to say yes.”—Evan Ratliff

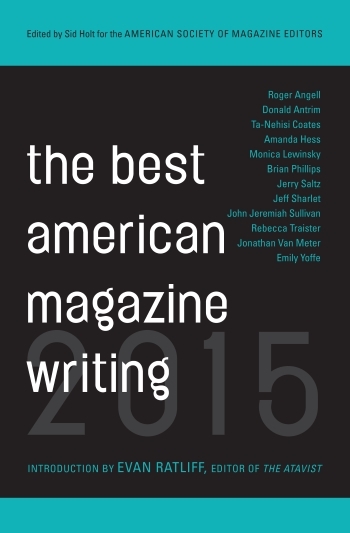

The following is an excerpt from Evan Ratliff’s introduction to The Best American Magazine Writing 2015:

Now, of course, the Internet has decimated the tattered remains of our attention span. Worse, we’re told that it has paradoxically fostered a new scourge for great magazine writing: more of it. In just the last five years, websites and magazines new and old— from Nautilus to BuzzFeed to Grantland to Th e Atavist, which I edit—have engaged in an ambitious resurgence in long, serious magazine writing. While this might seem like a sign of life, critics have explained that in fact such efforts are diminishing this great craft. Terms like “long-form” and hashtags like #longreads— through which readers recommend work they appreciate to other potential readers—only serve to dilute what was once the purview of discriminating enthusiasts alone. “The problem,” Jonathan Mahler wrote in the New York Times in 2014, “is that long-form stories are too often celebrated simply because they exist.” It was bad enough when our capacity to produce and read great stories collapsed. Now it seems we’ve turned around and loved magazine writing to death.

I don’t mean to make light of the real financial and even existential conundrums facing magazines today, of course. I only mean to observe that they have existed as long as magazines themselves. (Except that last one; complaints about too much magazine writing, and what we label it, seem to be this century’s peculiar, philistines-in-the-country-club anxiety.) In truth, I have my share of worries about the future of serious long-form journalism—who wouldn’t, knowing its history? But when it comes to explanations, I’m partial to one from the great Ian Frazier. It appeared in a 2002 essay introducing The Fish’s Eye, a collection of his writing on fishing, with pieces dating back to the 1970s. In those days, Frazier wrote:

Magazines regularly ran long nonfiction pieces, ambitious in style and content, that originated in the thoughts of individual writers, in their experiences and sensibilities, and in what they believed was important to say. . . . I’m not sure why this emphasis on writers took hold. Maybe it had to do with the fact that in those years America had recently and unexpectedly come unglued; perhaps people suspected that a writer out walking around in the midst of it would know more of what was going on than an editor behind a desk in New York. Neither do I know why that writers’ era should disappear. But it pretty much has, in magazines at any rate.

Frazier’s speculation—that perhaps the role of writers changes in relation to how often a chaotic world forces itself onto editors’ desks—strikes me as more believable than most. I would argue that the trend is not linear, however, but cyclical. Just as great magazines have always come and gone, so, too, have the periods where editors were more or less willing and able to assign ambitious stories.

Great magazine pieces, after all, grow out of a simple transaction: an editor saying yes to an idea and, in turn, to a writer. Yes to a writer who will risk her time and even safety to venture into the world and return with a story that makes sense of it. Yes to a writer brave enough to lay bare her own past as a window into an important issue. Yes to a writer who invests her intellect and humor into a fresh perspective on art or culture. (Of course, great magazine writing involves more than just saying yes. It involves the editor eventually saying no: no to lazy phrasing, no to shaky facts, no to reporting shortcuts. When long-form writing fails—as it did dangerously in widely discussed incidents in Grantland and Rolling Stone this past year, it is not because of the names we give it, the hashtags we apply to it, or its word-count ambitions. It fails because an editor declined to say no to facts that weren’t checked or to a piece whose ambition had overstepped its humanity.)

Therein lies the explanation for the volume in your hands, filled with work that stands in defiance of the latest doomsaying. What distinguishes the stories in this collection is not just their dedication to in-depth reporting and stylish storytelling. It is the decision of the editors behind them to assume the best of not just their writers but of their readers, in whatever medium those readers would encounter them. Indeed, anyone who takes the time to look at what’s behind the online thumbs-upping and recommending finds an audience craving depth and context precisely because they are awash in information, an audience begging to be moved because of the soulless content we bathe in daily.

This collection also reflects a time when America has, in Frazier’s words, “recently and unexpectedly come unglued.” A country still blinded to its failure to grapple with its history of racism and oppression requires a writer like Ta-Nehisi Coates in “The Case for Reparations.” The pitch to his editor at The Atlantic, Coates told me on the Longform Podcast last year, was simple: an argument could be made for reparations not through statistics and nineteenth-century history but through the narrative of those still suffering today from redlining in Chicago. “We really don’t even have to go back to slavery,” Coates said. “This wouldn’t have to be this old, musty thing.” An editor trusted him and said yes. And when Coates handed that editor a draft of some 13,000 words, “they came back to me and said: ‘We need more.’”

Similarly, the cauldron of hate for women that has erupted on the Internet requires a writer like Amanda Hess, deftly weaving together her personal experience with searing reporting in “Women Aren’t Welcome Here.” A culture seamlessly blending politics and celebrity is an occasion for Monica Lewinsky to tell her own, forgotten story in Vanity Fair. A generation of college students confronting the looming threat of rape on campus demands the thoughtful reflection of Emily Yoffe in Slate. Fourteen years of perpetual war in Afghanistan call for James Verini’s “Love and Ruin,” a story examining decades of interventions into that country’s history through the story of one woman. A nation celebrating its Olympic medal hoard while ignoring the host country’s homophobic laws requires the work of a reporter like Jeff Sharlet, who ventured to Moscow and St. Petersburg for GQ and returned with a deeply human portrait of the targets of those laws.

America’s tendency to ignore and discard its elderly—even as it faces a wave of aging baby boomers—demands Tiffany Stanley’s wrenching story, “Jackie’s Goodbye,” of caring for her aunt with Alzheimer’s. And it can do no better than the magical prose of New Yorker legend Roger Angell, laying bare the comedy and tragedy of aging, alongside the joy of a life well lived, in “Th is Old Man.”

It’s a reality that all of these stories and the institutions behind them—whether renowned ones like The New Yorker or upstarts like Pacific Standard and The Atavist—must now compete in a world saturated with information and distraction. It’s true that even the definition of a magazine has been stretched and twisted by a digital world that blows apart tables of contents and deposits them, story by story, on screens the size of a pack of cigarettes. With apologies to the collectors out there, however, this won’t be the final edition of The Best American Magazine Writing. Great writers will keep finding the wherewithal to chase the bold ideas, and great editors will keep finding ways to say yes.

Even better, the next era of magazine work can be one that is more diverse in the character of its writers and in the form of its work. It can be one in which ambitious experimentation is celebrated alongside tradition, one which encompasses the live shows of Pop Up Magazine on the West Coast, the evolving tradition of National Geographic, the design serenity of Nautilus , the raucous reporting of Vice. Perhaps magazines have to die every once in a while so that they may be born again for a new age. “I know people who say they don’t have a television,” Roger Angell told an interviewer, a few years back. “You better belong to the times you’re in.”