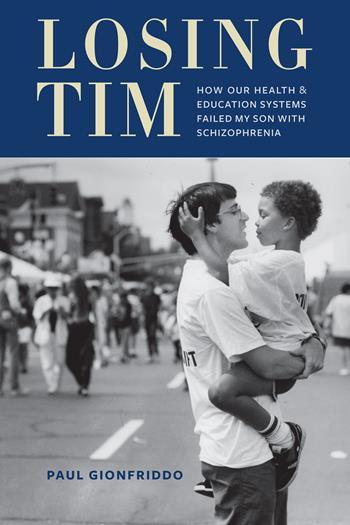

An Interview with Paul Gionfriddo, author of "Losing Tim"

The following is an interview with Paul Gionfriddo, author of Losing Tim: How Our Health and Education Systems Failed My Son with Schizophrenia:

The following is an interview with Paul Gionfriddo, author of Losing Tim: How Our Health and Education Systems Failed My Son with Schizophrenia:

Question: Losing Tim is a policy memoir, a reflection on your life as much as Tim’s. Can you talk about that?

Paul Gionfriddo: I was a state legislator in the 1980s, and helped build the failed community-based mental health system that we have today. Then I adopted an infant son who developed a serious mental illness when he was very young and had to live within the system I helped to build. And so over more than two decades, I experienced the effect of our policy decisions from the other side. And through writing the book, I’ve had the opportunity to make some sense of what we went through, and to say how we could do things differently to fix the problems we policymakers unintentionally created—and perhaps save some lives.

Q: But aren’t our options pretty limited when it comes to treating people with serious mental illnesses?

PG: Some people think so, but that’s usually because they only see serious mental illnesses in their later stages and think they are synonymous with violent tendencies. This is a myth that has led us to making jails our 21st century mental health institutions. The truth is that ten years typically pass from the time there are early symptoms of mental illnesses to the time we begin to treat them effectively. Those are ten years of lost opportunities to intervene early with the right diagnosis, the right drugs, the right therapies, and the right individual, family, and social supports—all of which can lead to recovery.

Q: You come down pretty hard on the educational system in Losing Tim. How come?

PG: It wasn’t really my intention to be hard on teachers or administrators. They have it hard enough. But it’s not helpful to pretend that what happened to Tim in school didn’t happen to him, and doesn’t happen to a lot of other children with serious mental illnesses. Many don’t get into special education in the first place. When they do, they frequently don’t get decent IEPs. Their community-based services aren’t made a part of their educational program. They are more frequently suspended or expelled than kids without disabilities. And they end up dropping out of school or life.

Q: What would you tell parents confronting similar issues in their children?

PG: Most of us don’t realize that half of all mental illnesses manifest by the age of 14. At that age, children have a limited set of supports—family, school, a pediatrician, friends, and perhaps some afterschool activities. It is critically important for parents to get all of these assets working together on behalf of the child. And that takes time. So don’t delay—it is better to overreact and then have to back off than to underreact and lose precious time as a disease progresses.

Even at the risk of being called “overprotective parents?”

Q: We’ve all been called that more than once, haven’t we!?

PG: Parents of kids with mental health concerns are often blamed – or blame themselves – for their child’s condition. We have to get over that, because the health and well-being of our kids is just as important as the health and well-being of every other child.

Q: Losing Tim has been described as “relentless,” with bad news coming on top of bad news. How did you cope with this in real time?

PG: I laughed a lot with Tim, usually about the absurdities we faced. I mention some of these in the book, like the time one provider asked Tim if he knew he was adopted—as if there could be any doubt at all about that in Tim’s mind! But I would also say that as I wrote, I realized that over time I became a little numb to it all because it was all “normal” to me. I worried more about the effect Tim’s illness had on my other children, who also grew up thinking that this kind of chaos was normal.

Q: You argue in Losing Tim that mental illnesses are like other chronic diseases, but that we treat people with mental illnesses differently from the way we treat people with other chronic conditions. What do you mean by this, and what would you do differently?

PG: By using a non-clinical standard—danger to self or others—as a trigger to treatment, mental illnesses are the only chronic conditions that as a matter of public policy we wait until Stage 4 to treat, and then often only through incarceration. Imagine the outcry if we treated cancers this way—neglecting them until they reached Stage 4, and then telling cancer patients who refused chemotherapy that because they were now endangering their lives, we would have to lock them up for their own good.

What we do with cancers, heart diseases, and other chronic conditions is promote screening and early detection, and then early and usually aggressive intervention so that people can recover. This is exactly what we should do with serious mental illnesses, too.

Q: If there were one central point you’d want readers to take away from Losing Tim, what would it be?

PG: That as a matter of public policy we are mired today in Stage 4 thinking, and we don’t have to be. All of our collective attention, all of our thinking, and all of our policy seems locked onto the picture that people with serious mental illnesses are always a danger to themselves or others and that we need to treat them is such. This is so wrong. They are people just like Tim—often kind and gentle, with hopes and dreams, who want to learn, work, and live independently. So they don’t have to end up in jail, on the streets, or dead. We just need to recognize that if we intervene early we can change the trajectories of their lives.

1 Response

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Paul’s points are right on target, and right from the mouth of someone who has firsthand knowledge of the mental health treatment ststems, the manner in which many view mental illness,

and is in a unique position from which to make his observations .

Policy makers: please read Paul’s writings, and actions accordingly.